7 Business

7.1 Annual

Plan 2020/21 - Draft 2020/21 Budget Options and Implications

File

Number: A11287638

Author: Jeremy

Boase, Manager: Strategy and Corporate Planning

Kathryn Sharplin, Manager:

Finance

Christine Jones, General

Manager: Strategy & Growth

Authoriser: Paul

Davidson, General Manager: Corporate Services

Purpose of the Report

1. This report seeks

the Committee’s direction on issues and options relevant to the draft

2020/21 Annual Plan budget prior to adoption of that draft document later in

March.

|

Recommendations

That the Policy Committee:

(a) Receives report ‘Annual

Plan 2020/21 - Draft 2020/21 Budget Options and Implications

(b) Notes that the Executive recommends

that the Policy Committee approves an Annual Plan budget package in the mid

to upper range of Options 3 and 4.

(c) Approves 2020/21 capital programme

of $x and associated rates revenue increase of x%.

(d) Recognises the rates

increase of x% is made up of:

(i) Business as usual

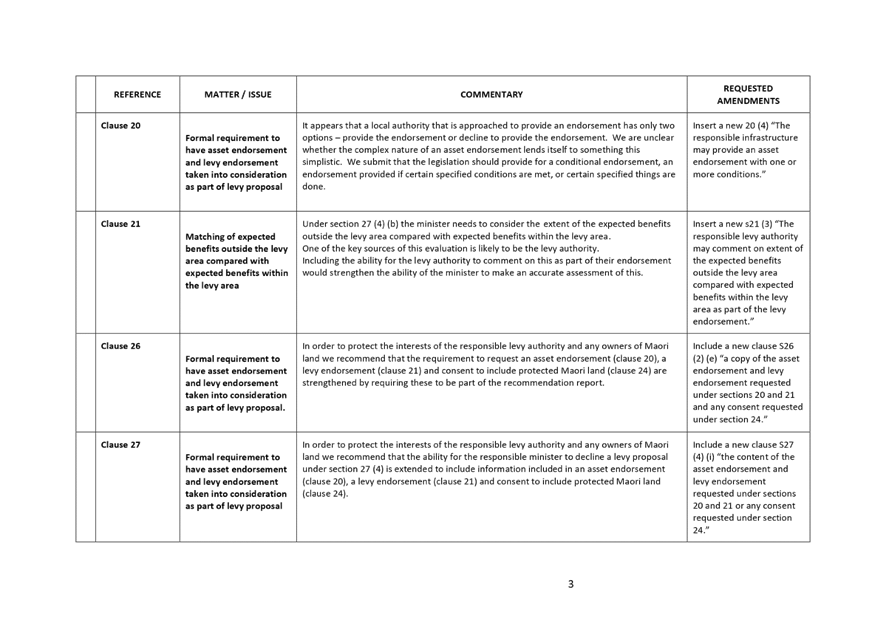

general rate x%

(ii) Waters x%

(iii) Growth & transport planning

x%

(iv) Debt management x%

(v) Other to reflect decisions

made during the meeting to add operating expenditure x%

(e) Approves a further amendment

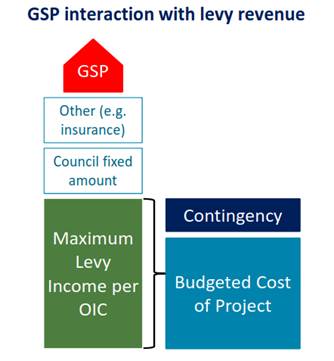

to the rating structure by reducing the uniform annual general charge to 10%

(over and above the reduction to 15% approved by Council in December).

(f) Agrees to assess and

review further opportunities to address Council’s funding and financing

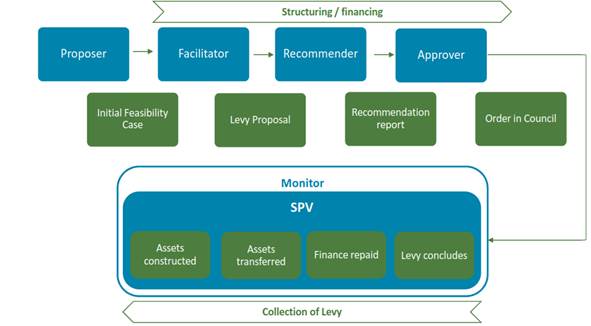

challenges with central government, regional local government partners, and

other growth councils.

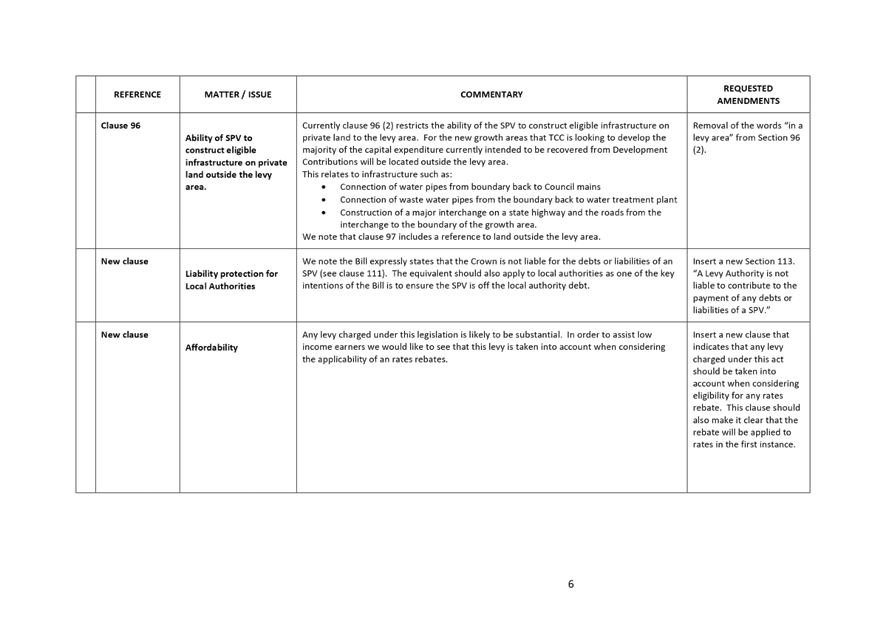

|

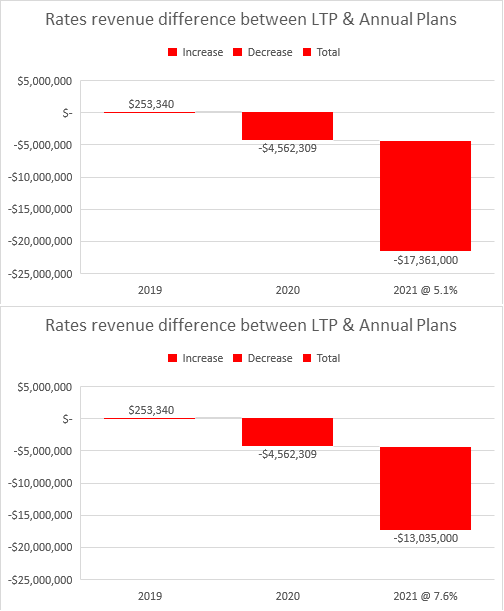

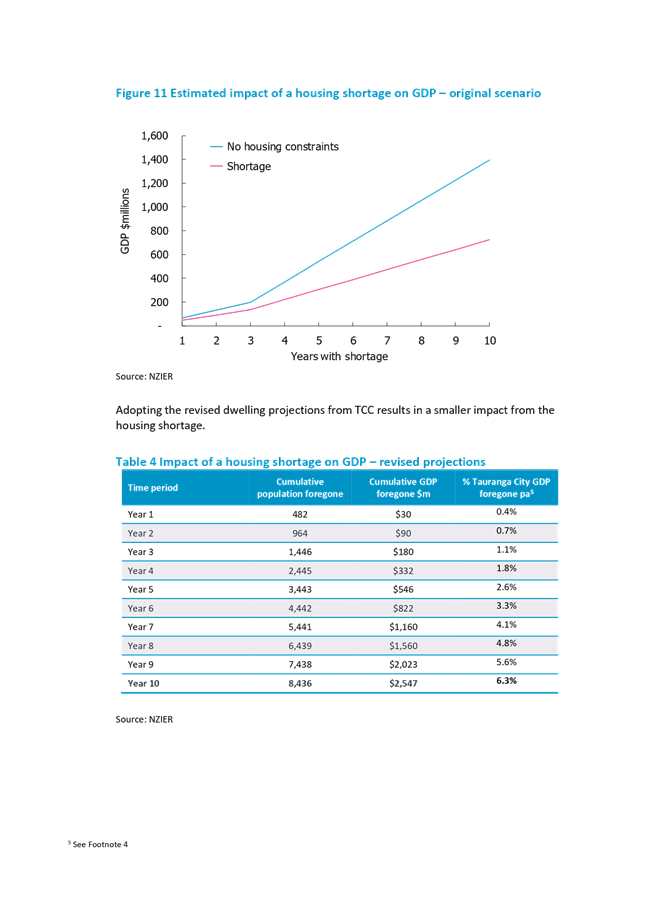

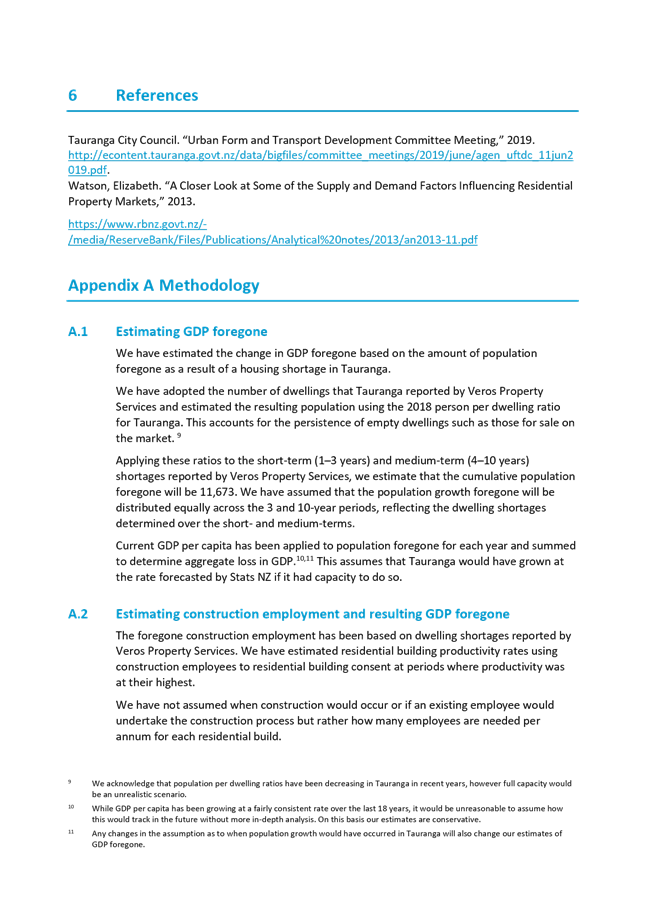

Executive Summary

2. Since the December

2019 Council meeting when the draft 2020/21 Annual Plan was first considered,

there have been a number of matters that have affected Council’s

financial outlook. These matters include additional capital budgets,

additional provisions for weathertightness claims, and the deferral of elder

housing divestment revenues.

3. The cumulative

effect of these matters is that the parameters for the draft Annual Plan that

were adopted by Council in December are no longer financially sustainable or prudent.

This affects both the short-term outlook as covered by the Annual Plan and the

medium-term outlook that will be addressed in next year’s Long-term

Plan.

4. While the matters

listed above create the immediate need for this report, there are deeper

underlying reasons for Council’s current financial situation. These

include systemic issues in the financing and funding of major infrastructure to

support population and industrial growth. These issues are shared by a

number of growth-affected councils who are working collectively with central

government on long-term solutions. These potential solutions, though,

will not be available in time to help address the issues faced with the draft

2020/21 Annual Plan, and nor will they be a sufficient toolkit to address those

issues and therefore further solutions are required.

5. The immediate

actions required to address Council’s current financial situation are to:

· prioritise capital expenditure

· increase revenue, and

· pay down debt

while commencing engagement with

the community and regional and national partners regarding the city’s and

the Council’s ongoing fiscal challenges, and starting to develop a plan

to investigate, evaluate and decide upon options for medium-term

solutions.

6. To ensure that sufficient

capital expenditure is budgeted to deliver on the growth and community needs of

the city, and to ensure that a meaningful contribution is made to paying down

debt, a significant rates increase is recommended.

7. To recognise the

potential impacts of such a rates increase on the ratepayers of lower valued

properties, it is also recommended that a further reduction in the uniform

annual general charge (being the ‘fixed’ element of individual

rates bills) be approved.

8. The matters

addressed in this report will not be ‘solved’ through this Annual

Plan process. Further work will be required through the 2021/31 Long-term

Plan process that Council will commence once the 2020/21 Annual Plan is

adopted.

Background – PART 1 – RECENT EVENTS

December Council report

9. On 10 December,

staff presented the Annual Plan 2020/21 indicative budget for Council’s

consideration. That report recommended an after-growth rates rise of 5.7%

split across residential

and commercial

ratepayers while noting that this was ‘significantly less than the

8.2% planned in the Long-term Plan’ and that this lower-than-planned

revenue ‘does not set a strong fiscal base for the Long-term Plan

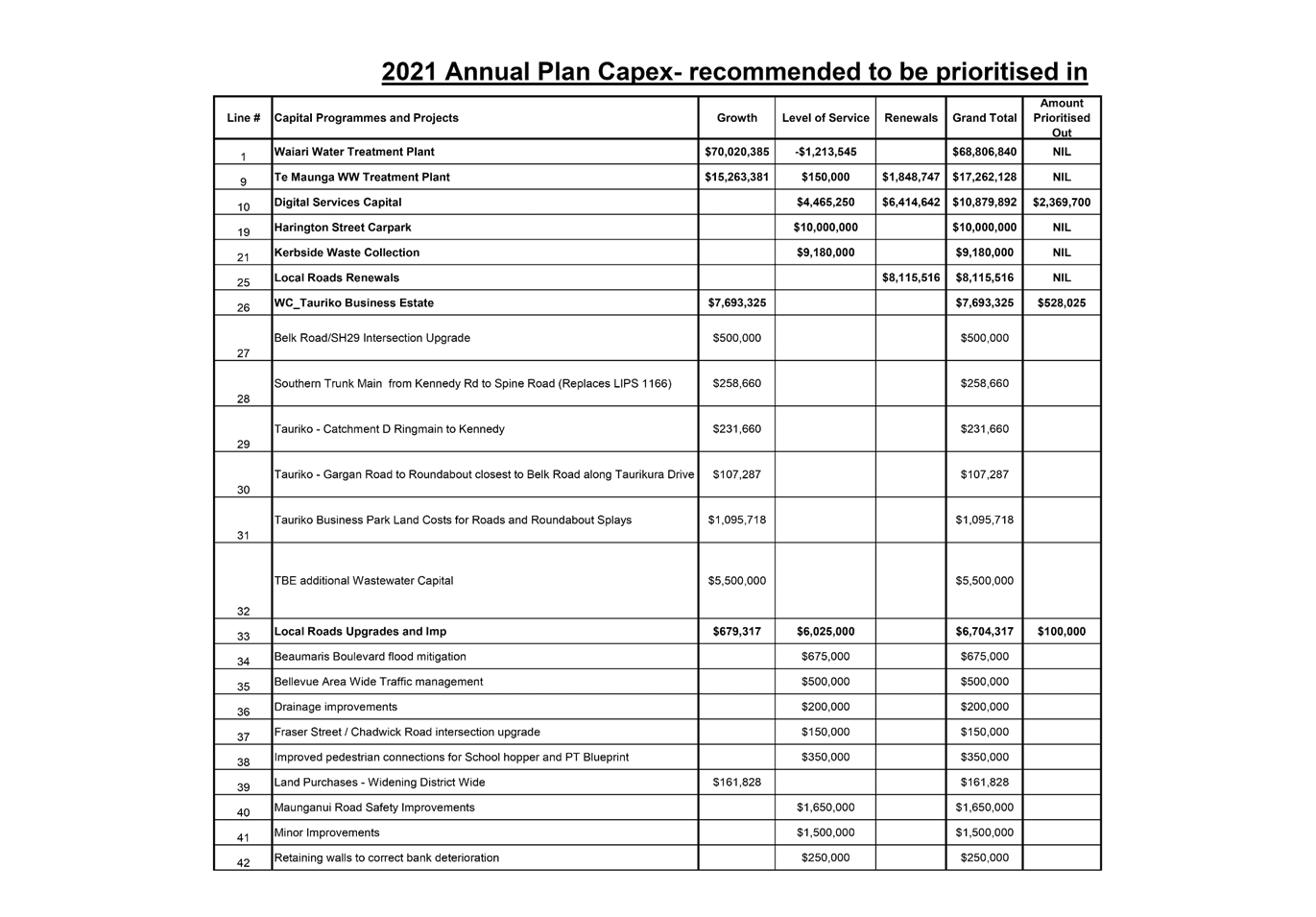

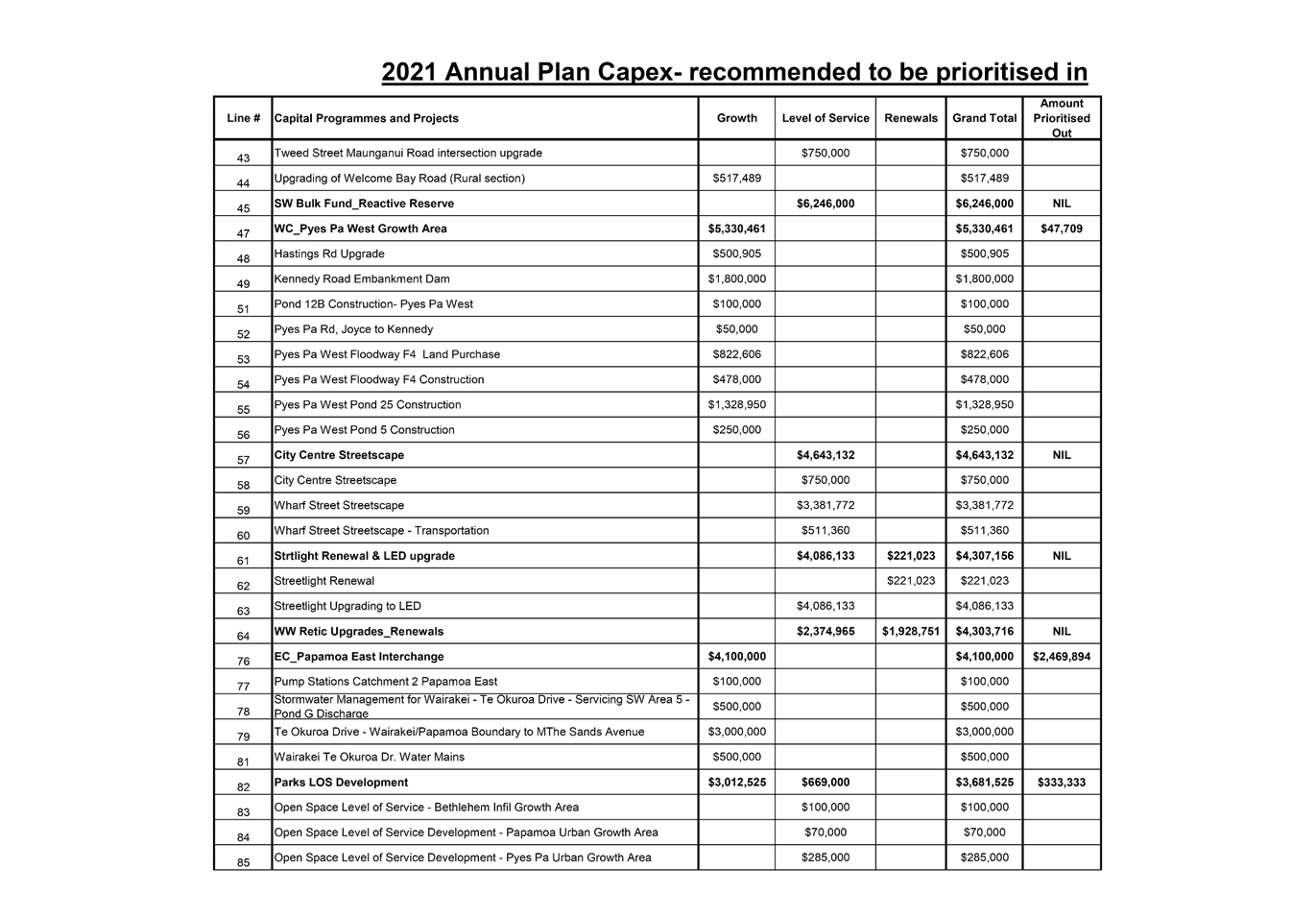

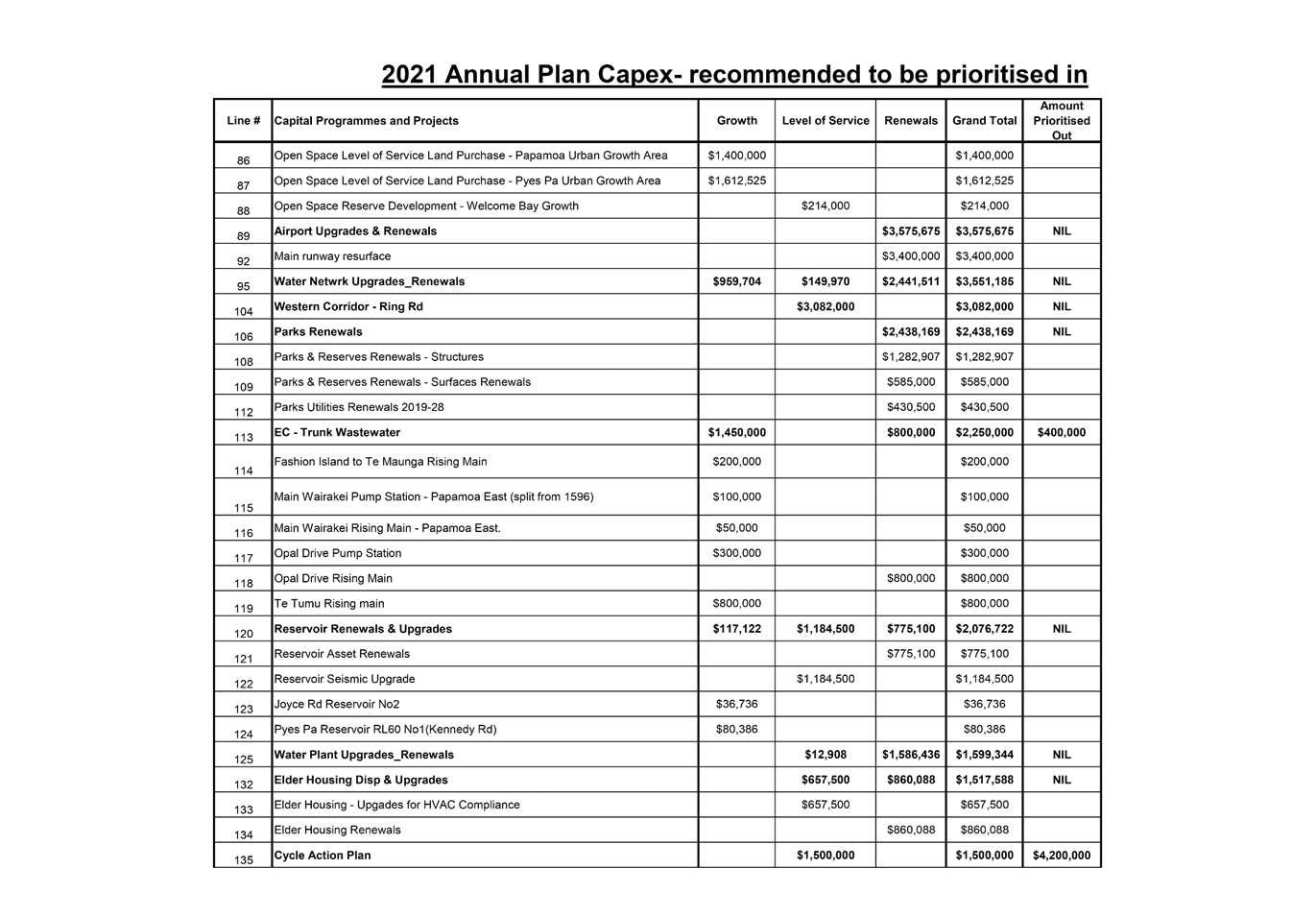

2021-31 and future years’.

10. In addition, the December

report also recommended that Council increase the contribution to the risk

reserve from the budgeted $1m to $4.4m in order to more quickly move that

reserve from its current deficit position.

11. In response to the December

report, Council resolved as follows:

(a) Agrees to continue with

year three of the rating structure changes to reduce the UAGC to 15% and

increase the commercial differential to 1.2%.

(b) Endorses in principle the

Annual Plan draft budget for capital and operations within the envelope of a

mean residential rates increase for 2020/21 of no more than forecast inflation

plus 2%

(i) Council to be

provided with options to achieve this rating level, together with the pros and

cons of these options.

(c) Notes that prior to

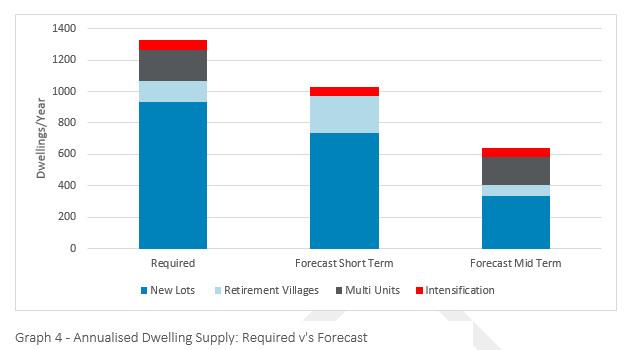

finalising the draft budget a further budget report will be provided to the

Policy Committee in February regarding:

(i) requests from Bay

Venues Ltd; and

(ii) any budget updates that

might arise from work currently underway.

12. The forecast inflation level

for 2021 is 1.9% meaning that resolution (b) above results in a mean

residential rate increase for 2020/21 of no more than 3.9%.

13. Council made no decision on

the recommended increase in contributions to the risk reserve, instead

resolving to leave the matter to ‘lie on the table’.

Events since December

Changes to

capital expenditure budgets

14. Since the December Council

meeting several updates have occurred which have implications for the 2020/21

budget. The most significant of these are briefly detailed below.

15. The

total budget to deliver the Waiāri water supply project

has increased impacting both the 2020/21 budget and future years’

budgets. The revised Waiāri budget was reported to the Projects,

Services & Operations Committee on 18 February. The recommended Waiāri

budget for 2020/21 is now $15.52 million more than it was in December.

|

|

20/21 budget

|

Future years’ budgets

|

Total remaining budget

|

|

Reported to

Council 10 Dec 2019

|

$53.29m

|

$23.30m

|

$76.59m

|

|

Budget as

proposed now

|

$68.81m

|

$26.23m

|

$95.04m

|

|

Difference

|

+$15.52m

|

+$2.93m

|

$18.45m

|

16. Note that when combined to

past years’ spending and the current year’s budget these figures

represent a total project budget of $177m as reported to the Projects, Services

& Operations Committee. This is the ‘P50’ budget, the

budget where modelling shows there to be a 50% likelihood of the final project

outcome being below the budget and a 50% likelihood of the final project

outcome being above it.

17. The increased budget estimate

for the Waiāri project results from market response to tenders and

physical conditions encountered during the early stages of construction.

The initial estimates were established following geotechnical testing, Monte

Carlo risk and cost forecasting, and peer reviews by both Council-appointed

external advisors and separately by Crown-appointed external advisors as part

of the Housing Infrastructure Fund process.

18. Weathertightness claims

have been reviewed and have increased potential costs to Council. The

extent of such claims was confidentially reported to the Finance, Audit and

Risk Committee on 25 February. A significant increase to Council’s

provision for future payments has been included in the revised draft

budget. This provision, while not capital expenditure, is debt funded and

therefore negatively affects debt capacity.

19. Bay Venues Limited

presented its plans for changes to its capital and operational budgets to the

Policy Committee on 19 February. The Committee resolved to include, for

the purposes of prioritisation at this meeting, an increase in new capital

budgets of $1.05m, an increase in renewal budgets of $1.31m, and an increase in

the rates-funded operating subsidy of $150,000 (together with increases in user

fees).

20. Additional work on the planning

of wastewater reticulation in the western corridor has identified an

accelerated need for additional infrastructure to service zoned and committed land,

including that on which the recently announced Winstone Wallboards factory is

proposed to be built. This programme of works has been estimated at $26m,

including $6.1 million in 2020/21 with the remaining costs spread over the

subsequent two years. This work will also provide interim solutions for

the next stages of industrial and residential land zoning in the area.

21. The 2020/21 budget for the

completion of the Harington Street carpark has been increased from $5.9m

to $10m. This reflects updated estimates for the practical cost of

remediation.

22. Other notable increases in

capital budgets since December include:

(a) Bringing forward from 2021/22

$3.7m related to the development of the Papamoa East Interchange

(b) A new project providing

additional capacity from the Oropi water treatment plant ($2.16m)

(c) Additional capital relating to

the Vessel Works wharf offloading project ($2.0m)

(d) Additional land purchase for

the western corridor ring road ($1.0m).

23. A number of other projects

have seen budgets reduced or deferred since December, though these do not

offset the increases listed above.

24. In addition to the items above

which have a direct impact on the 2020/21 budget, early planning for the

2021/31 Long-term Plan indicates significant increases to capital

expenditure budgets for growth areas, for resilience, and for social and

community infrastructure. Some of these growth-related water and

wastewater increases have already been reported to the Urban Form & Transport

Development Committee.

Potential

expenditure items not yet included in the draft budget

25. In addition to the items

above, which have all been incorporated in the revised draft budget, there are

a number of items where staff are aware of potential funding requests.

These potential funding requests have not yet been included in the revised

draft budget. For instance:

(a) The Tauranga Art Gallery

Trust has informally submitted a request for additional operating funding

of $259,000 relating to Mana Moana 2020, a significant new programme

celebrating our place in the Pacific. It will create a major city

centre/waterfront destination to stimulate business and foot traffic.

(b) Budgets are being prepared for

additional stakeholder engagement costs, subject to the outcome of an

informal briefing later in March.

(c) There is the potential for a

short-term funding request relating to the Our Place site on Willow

Street.

(d) A large group of key

stakeholders and practitioners are currently working together to develop a Sub-Regional

Homelessness Strategy. The action plan that is being developed alongside

that strategy, including prioritisation, will be delivered to all key

stakeholders, including Council by the end of March 2020. However, there is no

budget currently allocated to the delivery of any of the outcomes the strategy

is planned to address. Therefore, it is recommended that the Committee put

aside a bulk amount as part of the Annual Plan process to fund and drive key

initiatives that are prioritised through the development of the Western Bay of

Plenty Sub-Regional Homelessness Strategy.

(e) A potential street

ambassador function and resourcing for bylaw enforcement was approved in

principle by Council at its meeting of 27 February 2020 and referred to this

2020/21 Annual Plan prioritisation process.

(f) A range of upcoming land

purchases are required to facilitate the development of zoned growth areas

and to progress the readiness of future growth areas. This is

particularly so in the Pyes Pa / Tauriko area where projects such as the

western corridor ring road, southern connection to the Tauriko Business Estate

from SH29, interim access for Tauriko West from SH29, and improvements to the

Cambridge Road / SH29 intersection are being planned and progressed.

There is currently significant uncertainty around the timing and quantum

of some of these purchases. The approach that staff have taken in these

instances for the proposed annual plan capex budget is to include some

relatively small holding budgets. If additional budgets are required in

the 2020/21 financial year, they would be addressed on a case by case basis

through a report to Council.

Other budget changes that impact on Council’s

debt capacity

26. There are two other changes

that have been made since December that affect Council’s budgeted debt

levels and therefore its capacity to incur further debt.

27. The first of these is the

removal of the budgeted revenue from the divestment of Council’s elder

housing portfolio. This reflects the reasonable doubt that the divestment

(which is consistent with decisions made in the 2018/28 Long-term Plan process)

will be completed by the end of the 2020/21 financial year. The sale had

been budgeted to generate $23 million in 2020/21. The later timing of the

divestment will enable potential purchasers to utilise the provisions in the

upcoming residential intensification City Plan change to redevelop, creating

higher density on sites and therefore providing more housing stock. A

separate report on the elder housing divestment process is being prepared for

Council in April 2020.

28. The second change is the

reduction of the ‘capital adjustment’ or ‘smoothing’

project from the budget. This was a $35 million ‘negative’

project in the capital works schedule to recognise the estimated amount of work

that Council budgets for but is unable to complete in the year. This can

arise for reasons such as difficulty over land purchases or access, project

delays at planning or construction stage, or other matters beyond

Council’s control such as weather conditions or unforeseen ground

conditions. The recommended options later in this report include a

reduced $20 million capital adjustment to recognise the perceived greater

certainty over the projects retained in this year’s budget.

Impact of

events since December

29. The cumulative impact of

additional capital budgets, additional provisions for weathertightness claims,

the removal of elder housing divestment revenues, and the reduction in the

capital adjustment is an increase in projected debt of approximately $90 million.

Combined with the December resolution supporting a reduced mean residential

rate increase, this results in a draft Annual Plan budget that is not

financially sustainable or prudent.

30. The key ratio of

Council’s debt to its revenue nears its limit set both by Council and its

financiers. As is detailed later in this report, this situation is not

tenable.

31. Further, this issue is not

restricted to the draft 2020/21 Annual Plan budget. Early modelling

(using 2018/28 Long-term Plan budgets and known increases required in future

years) shows the 2021/31 Long-term Plan to be financially unsustainable across

multiple years.

32. This modelling indicates, over

the period of the next Long-Term Plan, a gap between the necessary capital

expenditure and Council’s ability to finance and fund that capital

expenditure of between $500 million and $1 billion.

background – part 2 – how we got here

Systemic issues

33. There is a broad

acknowledgement from independent analysts that the system of local government

funding, and particularly as it applies to high-growth councils such as

Tauranga, is not optimal.

34. In supporting the introduction

of the Infrastructure Funding and Financing Bill to Parliament in December

2019, Infrastructure New Zealand noted:

“The

biggest obstacle to adequate land supply, and therefore affordable housing, in New

Zealand’s cities is that our growth councils have insufficient funding

for this (roading and waters) local infrastructure.”[3]

35. Earlier, in a report titled Building

Regions, Infrastructure NZ summarised the planning and funding challenges

between central and local government as follows:

“…

an institutional system arrangement which misaligns roles, responsibilities and

resources across the public service.

“Central

government entities with national objectives are performing functions with

localised impacts. Local government entities without scale or resources are

providing services with regional and national impacts. Neither are optimised to

respond to the communities they are affecting and no one is delivering regional

outcomes.

“Two of

the most powerful governing responsibilities have been separated and isolated.

Planning is almost completely delegated to local government. Fourteen out of

every fifteen tax dollars is collected by central government. Central

organisations cannot plan and invest long term. Local organisations can plan,

but with little funding have no certainty as to whether plans can be delivered.

Neither are able to see the world through the same lens. Disagreement and

mistrust are pervasive.”[4]

36. In a series of reports

relating to housing, urban planning, and local government funding[5], the Productivity

Commission has recommended additional funding tools be made available to

help local government ensure that ‘growth pays for growth’.

37. The Commission’s 2019

report into Local government funding and financing recognises the issue

thus:

“The

failure of high-growth councils to supply enough infrastructure to meet demand

is a serious social and economic problem. Councils’ failure to adequately

accommodate growth has been a significant contributor to the undersupply of

development capacity for housing in fast-growing urban areas. This in turn has

been a major driver of rapid and harmful house price increases in New Zealand

since around 2000.

“Councils

have funding and financing tools to make growth “pay for itself”

over time by deriving revenue to fund the infrastructure for new property

developments from new residents rather than burdening existing ratepayers.

However, the long time it takes to recover costs, debt limits and the

perception that growth does not pay are significant barriers.”[6]

38. The Commission then provides

the following suggestions:

“For

funding and financing growth, the recommendations are to:

· give councils

the ability to levy some form of value capture using targeted rates on property

values associated with growth and infrastructure investment. This has the

potential to be a significant additional revenue source for high-growth urban

councils;

· enhance

councils’ ability to charge for road congestion, and wastewater (by

volume); and

· complete policy

work on and implement an enhanced version of Special Purpose Vehicles to help

high-growth councils nearing or at their debt limit to finance investment in

infrastructure to meet demand for growth.”[7]

Government response

39. The Government recognises the

existence of systemic funding and financing issues and has introduced

initiatives that attempt to address them.

40. In 2016 the Government

launched the Housing Infrastructure Fund (“HIF”), a

billion-dollar fund intended to accelerate the supply of new housing by

providing interest-free loans (for ten years) to councils in areas of high

housing need. This Council successfully sought HIF financing for the Waiāri

water supply project, the Te Tumu development, and the Te Maunga wastewater

treatment plant upgrades.

41. Note, however, that the effect

of the HIF was to lower interest rates on specific growth projects but that

there was no beneficial impact on overall debt levels or ratepayer costs.

In fact, because of changes to interest rates over time, the practical

implementation of the HIF has created a detrimental impact on

rates. This resulted in the Finance, Audit & Risk Committee

resolving in November 2019 to:

“Approve

that no further HIF drawdowns are undertaken for the remainder of the 2019/20

financial year or the 2020/21 Annual Plan unless a satisfactory conclusion is

made in relation to discussions with the Government.”

42. The draft 2020/21 Annual Plan

has consequently been prepared in accordance with the above resolution.

43. In December 2019, the

Government introduced the Infrastructure Funding and Financing Bill to

Parliament. The purpose of the Bill is:

“to

provide a funding and financial model for the provision of infrastructure for

housing and urban development, that—

(a) supports

the functioning of urban land markets; and

(b) reduces

the impact of local authority financing and funding constraints; and

(c) supports

community needs; and

(d) appropriately

allocates the costs of infrastructure.” (emphasis added)

44. Council’s proposed

submission to the Infrastructure Funding and Financing Bill is to be considered

by the Policy Committee on 4 March 2020.

Cumulative

revenue deficits

45. The 2018/28 Long-term Plan proposed

significantly higher rates increases in year 2 and 3 than were set through the

2019/20 Annual Plan and which were proposed by Council for 2020/21 at its 10

December meeting. The lower revenue achieved directly impacts Council’s

capacity to borrow to pay for new capital investment.

46. The cumulative impact of

setting rates lower than proposed in the Long-term Plan can be seen below in

two graphs, one assuming a 5.1% average rates increase (Option 1 later in this

report) and one assuming a 7.6% average rates increase (Option 2 later in this

report):

47. The cumulative impact over

just two years since the Long-term Plan was adopted (based on a 5.1% average

rates increase for 2020/21) is more than $21 million less income, while the

similar figure based on a 7.6% average rates increase is more than $17 million.

48. All

Long-term and Annual Plan processes require a trade-off between providing for

future investment, retaining debt headroom to respond to unforeseen risks, and

delivering rates increases that are affordable and acceptable to the

community. These issues have been raised by both the Executive and the

mayor and councillors through formal Council reports and through community

engagement on formally approved budgeting and planning documents. A small

sample of examples are included below.

49. The

2010/11 Annual Plan consultation document demonstrates the ongoing pressure

that this Council has faced for many years:

“Growth

demands continue to place significant pressure on the Council to find ways to

fund our city’s needs. It has created a funding problem, as affordability

restricts the Council from increasing rates sufficient to meet the full costs

of providing the infrastructure required. Long-term debt, used to help minimise

the impact on today’s ratepayers, will soon reach its prudent maximum

level.”

50. In

preparing for the 2011/12 Annual Plan, a report to Council[8] addressed the debt and

debt-to-revenue ratio issues thus:

“While

an expected net debt to operating revenue ratio of less than 260% is now

projected for the end of the 2011/12 financial year staff recommend that

Council take decisive action to meet the financial ratios within existing

Treasury Policy limits. The key reasons for doing this are:

· Ensure the fiscal position of Council is not weakened

further; and

· Provide some flexibility to respond to the medium to

long term fiscal issues which Council will face through the development of the

2012 – 2022 Ten Year Plan.”

51. More

recently, in preparing for the 2017/18 Annual Plan, a report to Council[9] includes the

following, which is very similar to the situation this year:

“Since

the development of the 2015-2025 Long Term Plan, levels of growth have occurred

that are significantly higher than were assumed in the LTP.

Infrastructure pressures from continued high levels of growth will put

significant pressure on Council’s balance sheet capacity in the 2017/18

and future years.

“In

addition, a number of external factors have resulted in a greater level of risk

for Council in managing its financial position going forward. Examples

include the greater risk around exposure for leaky home claims. Council needs

flexibility in its balance sheet. This can be attained through maintaining a

risk reserve together with debt headroom. Funding a risk reserve also

ensures that some risk is funded by existing ratepayers rather than transferring

significant risk to future ratepayers.

“TCC

is currently within its financial strategy limits for debt and the debt to

revenue ratio. However, the increase in debt to fund infrastructure earlier

than in the LTP means the 2017/18 debt level and debt to revenue ratio are

higher than they were in the LTP. On current assumptions, without intervention,

it would exceed some of its limits in the early years of the next LTP.”

52. Similar

statements to the above can be identified in most Annual Plan and Long-term

Plan processes over the past decade.

Debt funding operating expenditure

53. In general, operating

expenditure is funded from operating revenue. This is consistent with the

Local Government Act requirement that “a local authority must ensure

that each year’s projected operating revenues are set at a level

sufficient to meet that year’s projected operating expenses”

(section 100(1)).

54. Section 100(2) provides for

some exceptions to this rule, but the principle is clear.

55. Council’s Revenue &

Financing Policy mirrors the general principle of section 100(1) and states

that:

“Loans

will not be used to fund operating expenditure, unless it is otherwise resolved

by Council. Council may resolve to use loans to fund operating

expenditure where the expenditure provides benefits outside the year of

operation, such as community grants for assets.”

56. In recent years, Council has

resolved to finance a number of significant operating projects through

rate-funded loans. This has the effect of spreading the rating

burden of these projects across a number of years. In terms of

Council’s debt-to-revenue ratio, compared to rate-funding in the year

costs are incurred, it has the effect of increasing debt and reducing

revenue. Both of these implications have a negative effect on the ratio

and consequently Council’s ability to debt-fund other projects in the

future.

57. The recommended options

detailed later in this report seek to reverse these earlier decisions to

debt-fund operating expenses. If supported, this will increase revenue

and reduce debt.

Tauranga is not unique

58. While the specific

circumstances covered in this report relate to this Council, we are aware that

other councils are facing similar pressures.

59. For instance,

Thames-Coromandel District Council (“TCDC”) are proposing a 9.98%

average rate increase this year, which it attributes to “higher than

anticipated costs”. TCDC also note that “This proposed

rating increase is not enough to cover the total increase in operating costs,

so will require additional funding by borrowing which is achievable with a

short-term loan to reduce the rates increase and spread it out over subsequent

years, to lessen the burden on ratepayers.”[10]

60. The following table compares

the overall average rates cost (commercial and residential combined) of the

major metro councils.

|

Council

|

Total rates

2019/2020 (Incl. GST)

|

Average rates

per rating unit

|

|

Dunedin

|

$

180,194,300

|

$ 3,186

|

|

Christchurch

|

$

598,990,150

|

$ 3,449

|

|

Tauranga

|

$

205,471,650

|

$ 3,521

|

|

Hamilton

|

$

229,812,344

|

$ 3,871

|

|

Auckland

|

$

2,188,954,942

|

$ 3,889

|

|

Wellington

|

$

373,296,251

|

$ 4,717

|

61. These figures include water

rates (including water-by-meter where applicable) with the exception of

Auckland where both water and wastewater are charged through Watercare.

Also note that Auckland is a unitary authority with a consequently different

cost base to the other metros. Tauranga is the only metro shown here

without a kerbside waste collection in its cost structure. Adding

approximately $300 per rating unit would create a reasonable comparator.

62. For several years, Council has

been working with the other high-growth councils of Auckland, Hamilton and

Queenstown-Lakes regarding funding and financing challenges.

63. The growth councils have

sought to identify commonalities in growth challenges and potential

solutions. Through this forum the growth councils have engaged directly

with senior staff of the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development, the Ministry

of Transport, the New Zealand Transport Agency and the Department of Internal

Affairs. These discussions have been constructive, resulting in a common

understanding of the challenges and practical realities of managing growth and leading

to early conversations on potential solutions.

64. The engagement and commitment

of central government in the “Growth Councils’ Initiative” is

acknowledged and valued. There is a need to build on this goodwill and

move this work forward with a sense of pace and urgency.

65. In response to their own

funding challenges in the transport area, Auckland Council has successfully

lobbied the government for an additional fuel tax of 10 cents per litre of

petrol and diesel sold in the region. This raised $156 million in the

year to 30 June 2019.

66. Meanwhile, Queenstown-Lakes

District Council has been working closely with central government on a proposed

visitor levy (or ‘bed tax’) set at 5% of overnight accommodation

costs. This is projected to raise $22.5 million per annum to invest in

the infrastructure needed to support the tourism industry in the

district. A non-binding referendum in mid-2019 saw 80% of local

voters supporting the proposal. Enabling legislation has yet to be

introduced to Parliament.

background – part 3 – Prudent financial

management

Council’s debt thresholds

67. As part of each Long-Term

Plan, Council adopts its financial strategy. Within the financial

strategy are a number of quantified limits and targets for rates and borrowing.

68. One of these limits relates to

the level of external debt to annual operating revenue. Council has

established a maximum limit of 250% for this ratio. This is the same

level that is set as a maximum by the body from which Council secures the majority

of its debt finance, the Local Government Funding Agency (“LGFA”).

69. Because there are serious

implications should Council breach the 250% limit, in previous Long-term Plans

Council has set itself a lower limit of 225%. The reasons why this

approach was not taken in the 2018 Long-term Plan are set out in the financial

strategy thus:

“Maintain

debt headroom. In the previous LTP, the maximum debt to revenue ratio was

set below the Treasury policy maximum at 225% to allow some debt headroom in

the event of unforeseen events and to provide capacity for expected high levels

of capital expenditure outside the ten years. For this LTP the lower

limit is not maintained because it is not possible to achieve the

infrastructure requirements in the middle and later years of the LTP within

this limit. However, the Treasury limit of 250% is maintained as an upper

limit. The debt to revenue ratio throughout the LTP remains below the

maximum providing a level of debt headroom should unforeseen events occur.

Over time, it is prudent to aim for further reduction to ensure debt capacity

for renewals of existing assets and to provide capacity for unforeseen

events.”

70. It is the opinion of staff

that a return to a self-imposed upper limit of 225% demonstrates prudent financial

management. As such, the options outlined later in this report assume a

maximum budgeted debt to revenue ratio of 225%.

Consequences of breaching the LGFA threshold

71. In the event that Council

breaches the LGFA limit of 250% the consequences are significant.

72. In short, Council would be in

breach of its borrowing covenants. Those covenants provide a brief period

to allow Council to rectify the breach, but if Council were unable to so

rectify then the LGFA would require repayment of all of its debt issued to

Council. This would require Council to refinance over $500 million of

debt almost instantly.

73. The direct costs of

refinancing Council’s debt would be reflected in the interest rates

charged and the available terms of debt from other lenders.

Council’s treasury staff advise that the interest rates and, in

particular, the terms of loans would be significantly disadvantageous to

Council if refinancing was required. The additional cost of financing if

the limits were breached is estimated at a more than 1% increase of rates

initially, increasing as debt increases.

74. The indirect costs of

refinancing Council’s debt portfolio reflect the reputational and

governance risks associated with expulsion from the Crown-supported LGFA model.

These costs are difficult to measure but would also be significant for the

organisation and thus the city.

Risk reserve

75. As

noted above, at its 10 December meeting Council considered and then resolved to

leave ‘lie on the table’ the matter of its risk reserve.

76. The

key points made in the December report relating to the risk reserve were:

· Council maintains

a risk management fund (risk reserve) to fund unforeseen events that occur in

the city that are not covered by insurance. The risk reserve also helps

council manage financial risk.

· As of 30 June

2019, the fund was $15.5m in deficit. This is largely a result of Bella Vista

recovery costs and provisions relating to weathertight homes claims.

· The deficit is not

a cash deficit but reflects Council’s expected exposure in the medium

term.

· To build the

reserve (or rebuild it given it is currently in deficit), Council currently

adds around $1 million per year to the reserve.

· If no further

events occur that need to be funded from the risk reserve, this means that the

‘reserve’ will be returned to a zero balance in 15 years.

· The level of

funding in the reserve has been identified as a critical risk on the corporate

risk register.

77. The

December report recommended that the contribution to rebuilding the risk

reserve should be increased from the budgeted $1 million in 2020/21 to $4.4

million. This increase equated to a 2% increase in rates.

78. Since

December, and as noted earlier in this report, Council’s exposure to

weathertightness claims has increased. Consequently, the revised draft

budget for 2020/21 assumes borrowing will be higher to fund weathertightness

liabilities next year.

79. The

issue of the risk reserve has been raised by staff over a number of

years. On occasions Council has decided, against staff advice, to

decrease contributions into the reserve. For example, the 2018/28

Long-Term Plan saw zero contribution to the risk reserve, with the following

explanation in the document (page 23):

“Maintain a risk reserve.

A risk reserve is maintained to provide annual revenue to manage potential

risks and response to unforeseen events. In year 1 there is no

contribution to risk reserve but a contribution has been included from year 2 onwards.

The contribution to this risk reserve has been reduced from current levels,

recognising that other risk tools are being utilised. In particular, ratepayers

are being required to fund unusually high investment in new assets and services

and placeholder budgets for resilience have been included. Further

investigations of resilience will allow for a more targeted approach in

managing the risks.”

80. The

recommended options detailed later in this report address the challenges of the

risk reserve and the need to obtain debt headroom to address unforeseen costs

in the future such as those that arise from extreme weather events. We

recommend a significant increase in the contribution to the risk reserve.

This approach has the impact of both increasing Council’s revenue and

decreasing its debt.

Council’s operational cost structure

81. Council’s operating

expenditure in the draft 2020/21 Annual Plan budget is $284 million.

Within this, a large proportion of costs are the direct result of past

decisions (for example, debt servicing and depreciation costs) or are

‘locked in’ via long-term contracts (such as for repairs and

maintenance on roads or water networks) or are directly related to the delivery

of agreed service levels to the community.

82. Note that some of these costs

have had significant year-on-year increases reflected in the draft

budget. For example, the electricity budget has increased 12.7% from

$5.95 million in 2019/20 to $6.71 million, while the insurance budget has

increased 43.2% from $1.96 million to $2.81 million.

83. As such, the level of

operating costs that is influenceable on a year-by-year basis is considerably

less than the $284 million. The following table illustrates this point:

|

|

2020/21 draft budget

|

|

Personnel expenses

|

$69.6m

|

|

Depreciation & amortisation expenses

|

$63.5m

|

|

Finance expenses (interest)

|

$25.6m

|

|

Contracts (e.g. repairs & maint.)

|

$32.7m

|

|

Electricity

|

$6.7m

|

|

Insurance

|

$2.8m

|

|

|

$200.9m

|

84. The remaining costs in the

draft budget are under regular review by the Executive. While potential

reductions in some operating budgets have been identified for consideration

later in this report, in totality the operating budgets are considered to be

prudent and necessary for the delivery of services to the community.

Changing operational budgets is therefore not considered to be a significant

lever in attempting to address Council’s financial position.

background – part 4 – The city’s future

85. While

much of this report understandably deals with budgeted costs, revenues, and

debt (the Annual Plan process is, after all, a resource allocation and

cost-recovery process), the key question that underlines the discussion has to

be What do we want our city to be?

86. Engagement

processes, including the recently-completed Vital Update survey, consistently

tell us that the city’s communities share aspirations for a

‘better’ city. Whether this involves improved transport

solutions, increased social amenity, enhanced protection and development of

natural features, or a range of other interventions by Council or other

agencies, there is invariably a cost attached.

87. To

prosper as a city we need financial support, both from our current residents

and, in the medium-term, from other partners.

88. This

financial support, particularly from our current residents, highlights another

underlying question, being What level of contribution is affordable for our

communities?

89. As

previously advised a programme is underway to create a city-wide vision and

supporting actions plan in collaboration with key partners and

communities. A first step in the programme has been to complete a

Vital Update survey in partnership with Acorn Foundation, TECT and BayTrust.

This survey was conducted from mid-November 2019 to mid-February 2020 and

resulted in over 5,000 respondents.

90. The

draft and interim results may assist the Mayor and Councillors in prioritising

Council investment through the Annual Plan. It is intended that further

work will be undertaken to more meaningfully inform the Long-term Plan decision

making process.

91. Key

interim results from the survey include:

· ‘Main

reason you love living in Tauranga”; 42% love nature and being close

to the beach and consider Tauranga a beautiful place to live

· “If you

could change on thing about Tauranga what would it be?”; 42% noted

less congestion, better roading infrastructure and better parking in the CBD

and the Mount

· “Is there

anything in Tauranga that needs to be preserved/protected for the city to

continue to thrive in the next 10 years?”; 42% say protecting

and providing more green spaces, natural environment, reserves and having more

trees

· “Do you

have any other comments about the future of Tauranga?”; Better roading

infrastructure (27%), public transport (13%), and stronger leadership (14%) are

the most important topics identified.

92. There is strong alignment between

the survey findings and Council’s 2018/28 Long-term Plan. The

Long-term Plan identified moving around the city (transportation) and increased

environmental standards (protecting and caring for our natural environment) as

two of the city’s biggest challenges. The other two key challenges

addressed through the Long-term Plan are resilience and land supply /

urban form.

proposed approach

93. In

considering the issues raised in the sections above, this report recognises

that the 2020/21 Annual Plan, in whatever final form, will not provide all of

the solutions. Instead, this report recognises that there are short-term

responses that need to be taken through the Annual Plan and then further

consideration of the same issues through a medium-term lens via next

year’s Long-Term Plan.

94. Critical

to this two-step process is that short-term actions through the Annual Plan

should support the necessary ‘direction of travel’ for the

medium-term responses through the Long-Term Plan.

Short-term – 2020/21 Annual Plan

95. For the Annual Plan, the

immediate actions to consider include:

(a) Prioritising capital

expenditure by deciding what it is that needs to be delivered in the coming

year, conscious of the impacts of not delivering other projects that are

deferred or otherwise prioritised out

(b) Increasing revenue

whilst being conscious of the impact on those providing the revenue

(c) Committing to pay down debt

(d) Commencing engagement

with the community and with regional and national partners regarding the city’s

and Council’s ongoing fiscal challenges, noting that Council’s

credibility in such engagements will at least in part be dependent on the

choices it makes on items (a) to (c) above

(e) Commencing development of a

plan to investigate, evaluate and decide upon options for medium-term

solutions.

Medium-term – 2021/31 Long-Term Plan

96. For the Long-Term Plan, the

likely actions include:

(a) A continuation of the

budgeting actions initiated through the Annual Plan

(b) Further development of

engagement with regional and national partners on alternative funding and

financing approaches that help enable the city to prosper

(c) Consideration of funding and

service delivery options such as asset sales or amending service levels

(d) Continuing engagement with the

community on the future of the city and the financial and delivery tools needed

to realise that future.

97. The options presented in this

report relate to the 2020/21 Annual Plan only. However, as noted above,

it is recommended that these options are considered in light of the wider

discussion around the city’s form, funding and relationships that will

occur through the Long-Term Plan process. The impact of short-term

decisions on potential long-term partnership opportunities should be a consideration

in decision-making.

Options Analysis - framing

98. The

following section provides four core options or scenarios for

consideration. The nature of decision-making regarding budgets means that

there are countless other scenarios that may be considered and as such the four

options are presented as examples for the purpose of a simpler decision-making

process.

99. In

creating these options a four-step process was identified. The Committee

may find it useful to follow the same four-step process, being:

(a) First

determine what needs to be delivered (predominantly in the capital expenditure

sphere given the importance of the debt-to-revenue ratio)

(b) Then

determine the appropriate debt-to-revenue ratio (to both demonstrate prudent

financial management and to ensure that Council’s financial positioning

entering the Long-Term Plan process is acceptable)

(c) Then

determine operational areas of priority and assess potential increases and

potential decreases to operating expenditure in light of those priorities (this

may include some of the items noted in the ‘Potential expenditure

items not yet included in the draft budget’ section earlier in this

report)

(d) Then

identify the revenue and the split of revenue sources to deliver on (a) to (c)

above. If Council considers the resultant revenue level is not

appropriate, it will need to identify the change required and review the

capital and operational areas of priority.

100. In

regard to the split of revenue sources, a separate set of options regarding the

rating model is presented for consideration.

Capital

expenditure prioritisation

101. In

preparing the options, staff and the Executive have prioritised capital

expenditure in three categories of expenditure (being renewals, growth, and

level of service investment) and into three categories for decision-making

purposes, being:

(a) Projects

and initiatives included in the draft 2020/21 capital budget

(b) Projects

and initiatives recommended for political consideration before inclusion in the

draft 2020/21 capital budget

(c) Projects

and initiatives deferred and not included in the draft 2020/21 capital budget.

102. The

criteria for making these assessments is outlined graphically in Attachment

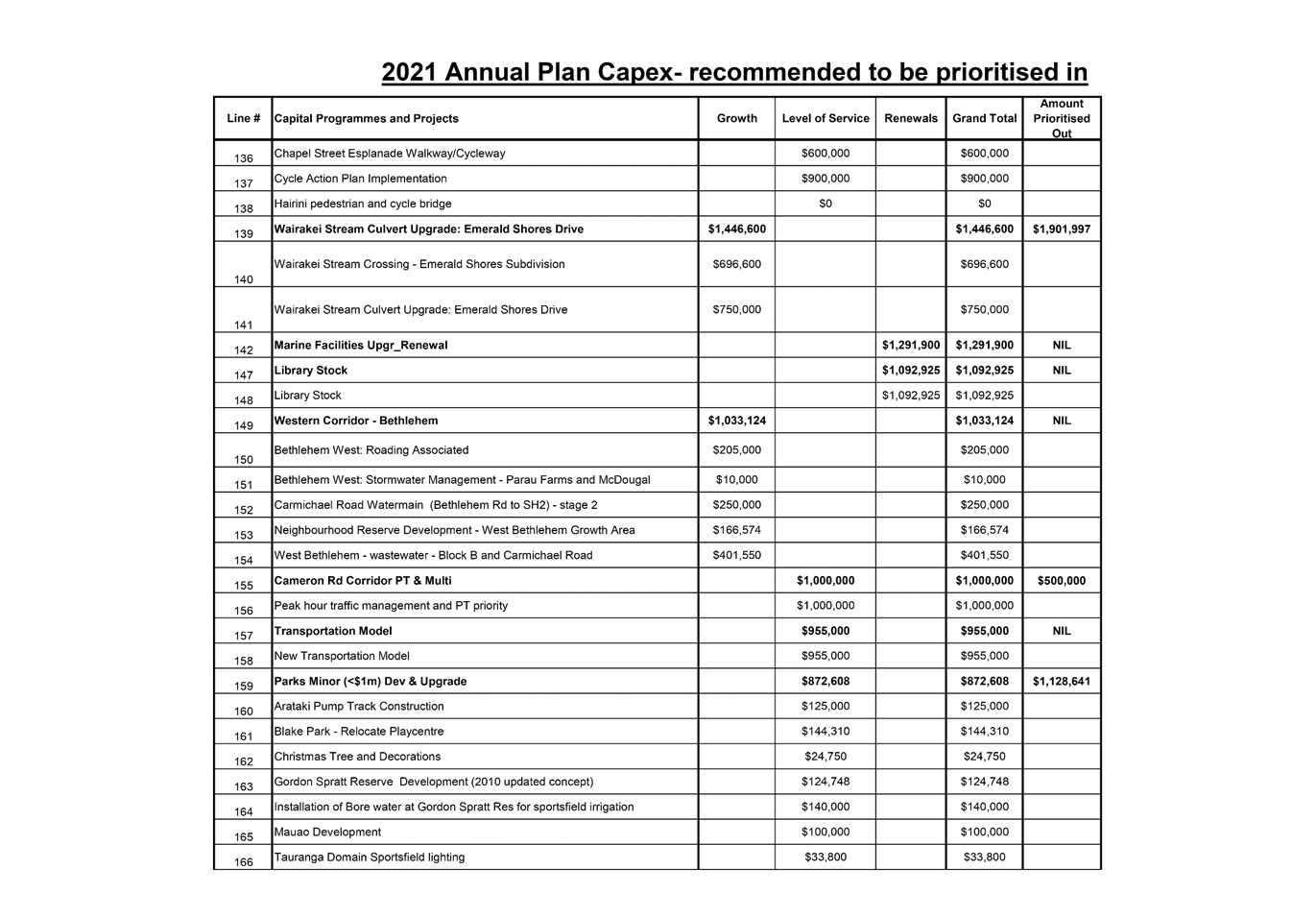

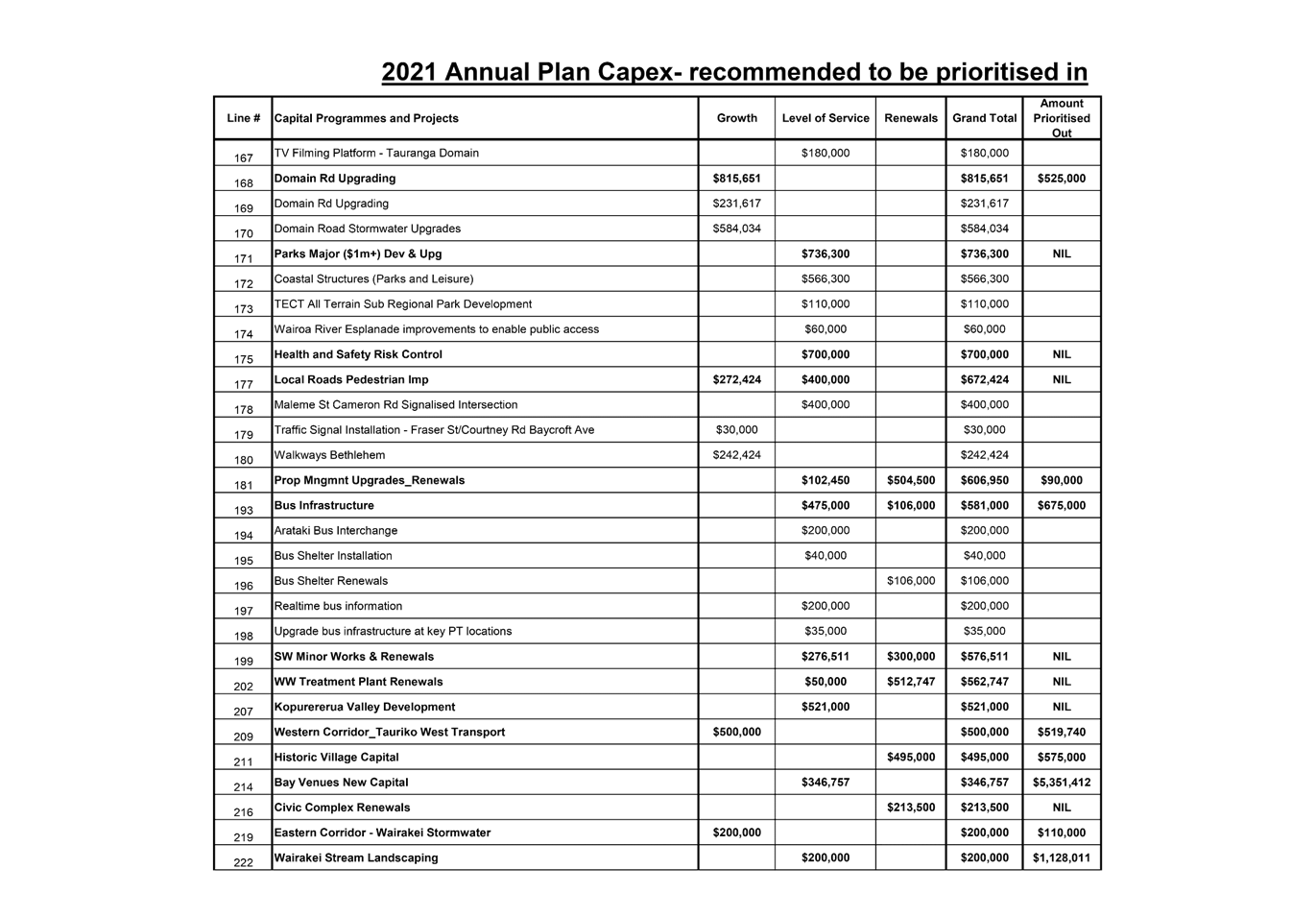

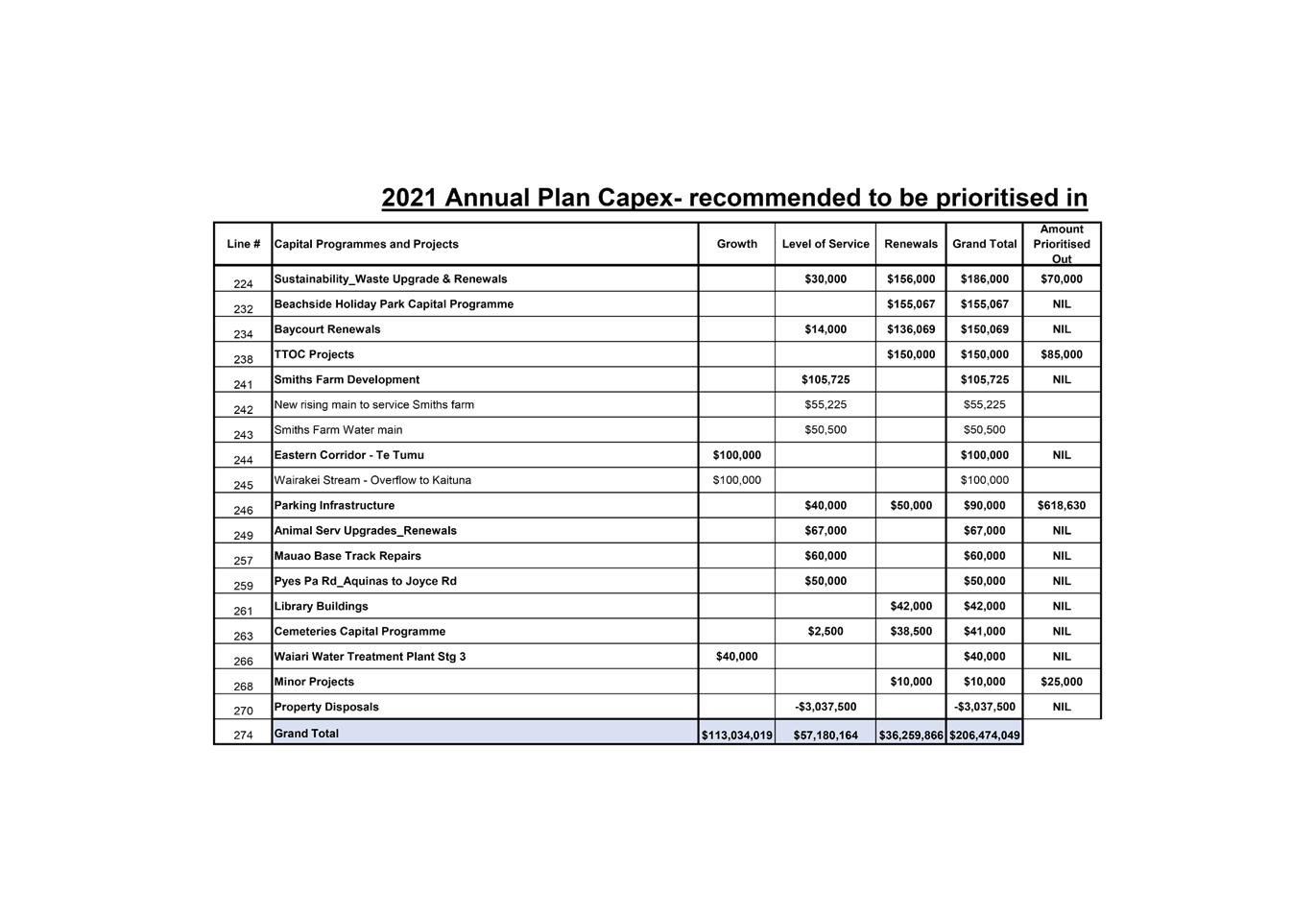

1 to this report.

103. The

total value of the current draft 2020/21 capital expenditure budget is $207

million. The summarised list of capital projects and programmes is

included as Attachment 2 to this report.

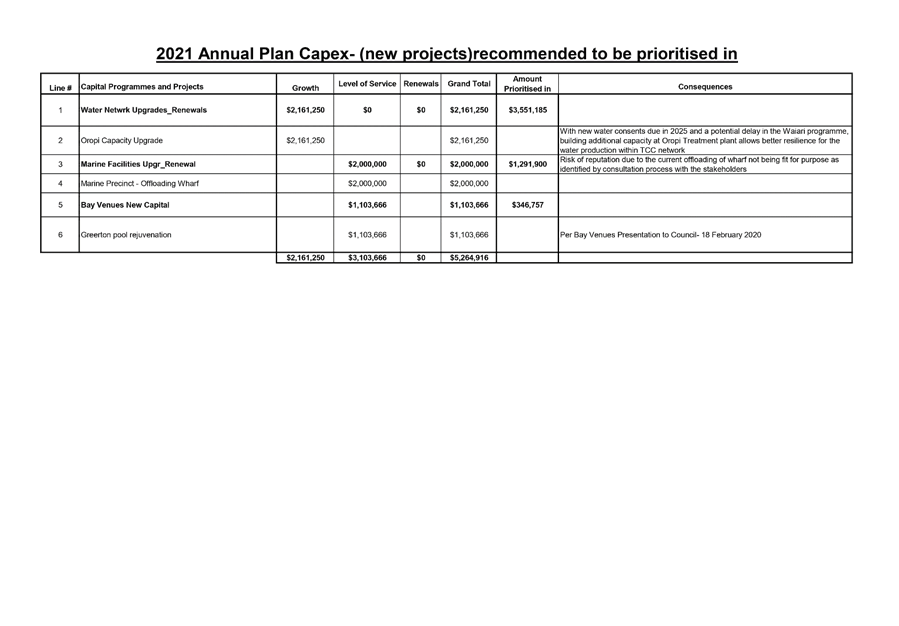

104. The

projects recommended for political consideration before inclusion in the draft

2020/21 capital expenditure budget total $5 million and are listed in Attachment

3 to this report.

105. The

projects originally intended for the 2020/21 budget but subsequently recommended

to be deferred total $36 million and are listed in Attachment 4 to this

report.

106. It

is recognised that there are many projects on both the ‘for

consideration’ and ‘deferred’ lists for which there are valid

and arguably compelling reasons for inclusion in the draft 2020/21 Annual

Plan. This is the crux of the issue. Even with significant revenue

increases Council does not have the financial capacity to do all that it would

like to do.

107. Each

of the four options assumes a ‘capital adjustment’ or

‘smoothing’ project of $20 million to recognise the likelihood

of not all budgeted projects being delivered in the year planned. This is

a reduced level from prior years in recognition of the fact that the capital

budgets have been closely reviewed to ensure that only deliverable projects are

included.

Preferred

debt-to-revenue ratio

108. In

considering Council’s current and expected financial state, the Executive

recommends reverting to a target for the debt-to-revenue ratio of 225%.

This:

(a) Will

ensure financial ‘headroom’ to allow Council to borrow for

unforeseen circumstances without risking breaching LGFA covenants; and

(b) Is

consistent with a ‘direction of travel’ that is likely to be

recommended as Council commences the Long-Term Plan process.

109. As

such, each of the options presented below includes a presumption of a 225%

limit for the debt-to-revenue ratio.

Operating

expenditure levels

110. As

noted earlier in this report, the operating expenditure budget has been the

focus of considerable attention by staff and the Executive. The current

budget is considered by the Executive to be

‘fit-for-purpose’.

111. If

the Committee wishes to pursue an approach of reducing operating expenditure,

the Executive has prepared some options to achieve this. However, none of

these options for reductions have yet been incorporated into the draft budget.

112. Likewise,

there are several potential increases to operating budgets that have been

identified elsewhere in this report for consideration. These have yet to

be included in the budget. Should the Committee decide to include some or

all of these items then that will naturally have an impact on the financials

under each option.

Revenue

levels

113. With

the operating and capital expenditure (and therefore debt) figures established,

and with a preferred debt-to-revenue maximum set, the required revenue figure

(and therefore the rates requirement) is calculated as a consequence for each

option.

114. The

exception to this approach is Option 1 whereby the limiting factor is the

permissible revenue levels which then consequently restricts the level of

capital expenditure and debt.

Structural

Options to address Funding & Financing Challenges

115. There

are a number of challenges facing growth councils given the need to invest in

significant infrastructure to support the supply of serviced residential and

employment land, to provide an effective functioning transport network, and to build

strong communities. The key issues include:

· The current

funding and financing model does not align incentives i.e. capital

infrastructure costs sit with local government while the bulk of the tax

revenue generated by the growth in economic activity goes to central

government.

· Recent initiatives

have been taken to boost the toolkit (including Housing Infrastructure Fund,

Infrastructure Funding & Financing legislation), however multiple solutions

are needed as these do not provide sufficient financial capacity on their own.

· Sub-regional and

regional outcomes will be impacted if this investment is curtailed and

therefore we need to work sub-regionally and regionally as part of the

solution.

· Housing

affordability, economic activity and employment will be detrimentally affected

through the inability of Council to deliver growth infrastructure in a fiscally

sustainable manner. This is occurring. The pace and scale at which the

issue can be responded to will determine the size and timeframe of impact.

116. It is proposed that a comprehensive

package of solutions be explored with our key regional and national partners,

with viable options progressing into the 2021/31 Long-term Plan process.

This will include an assessment of opportunities to leverage TCC’s

existing assets and funding sources.

options analysis – capex, debt and revenue models

117. The following section sets out the four

options that have been developed. Following the narrative section, a

table is included that summarises the key financial characteristics of the

options.

Option 1 – Consistent with December resolution

118. This option responds to Council’s

decision in December to provide for a mean residential rate increase of no more

than inflation (projected to be 1.9%) plus 2%.

119. By maintaining an overall rates increase

of 5.1% (which is consistent with a mean residential rates increase of 3.9% and

a larger mean commercial rates increase), this option requires removal of

approximately $33 million of capital expenditure from the current recommended

budget (and naturally no inclusion of additional projects from the ‘for

consideration’ list).

120. Under this Option the Committee would

need to identify the projects it wishes to be removed from the draft Annual

Plan.

121. This reduction of the capital expenditure

budget (depending somewhat on the specific projects that the Committee

determine should be removed) is likely to negatively impact on:

(a) The delivery of infrastructure

to currently zoned development areas

(b) Consequently, the availability

of new housing

(c) The delivery of traffic and

transport solutions across the city

(d) Other amenity projects.

122. In addition, in order to prepare a

balanced budget this option requires a reduction in operating expenditure of

approximately $4.3 million.

123. The Executive commenced a project in late

2019 seeking realistic budget savings across the organisation that did not

result in significant impacts on service delivery. That list totals

approximately $950,000 and is included as Attachment 5 to this report.

124. If all of these opportunities are

accepted, the Committee would need to work with staff and the Executive to

agree a further $3.3 million of operational expenditure reductions. This

will undoubtedly have a direct negative effect on services to the community

either in the short-term or the long-term.

125. This option is not recommended.

Option 2 – Constrained capital expenditure

126. This option also reduces the capital

expenditure budget but by a lesser amount than Option 1 ($24 million rather

than $33 million). This option is still of a scale likely (depending on

the projects that the Committee choose to remove) to negatively impact on:

(a) The delivery of infrastructure

to currently zoned development areas

(b) Consequently, the availability

of new housing

(c) The delivery of traffic and

transport solutions across the city

(d) Other amenity projects.

127. This option allows for the operating

expenditure budget to remain as is, but doesn’t currently provide for any

of the ‘not yet budgeted’ items listed earlier in this

report. The Committee would need to specifically resolve to include any

such items as it sees fit.

128. With regards to the rating impact, this

option keeps the ‘business as usual’ average rates increase at 3.9%

but separately recognises the distinct cost pressures in two key areas of

Council’s operations. These are:

(a) Transport and urban planning

and delivery, and

(b) Water and wastewater planning

and delivery.

129. The beyond-business-as-usual impact of

these two workstreams contribute to general rate rises of approximately 1.5%

and 2.2% respectively. As such, the total rates increase under this

option equates to 7.6%.

130. This option contributes nothing directly

to debt retirement.

131. This option is not

recommended.

Option 3 – Prioritised capital expenditure plus

limited debt management

132. This option allows for full delivery of

the proposed capital expenditure programme and the ‘for

consideration’ list, but only provides minimal scope ($6 million) for the

inclusion of projects currently included on the ‘deferred’

list.

133. While this is preferable to the

constrained delivery under Options 1 and 2, it is still a level of capital

expenditure delivery that is considered to be the ‘bare minimum’ to

provide for growth and for community needs. There will remain projects on

the ‘deferred’ list that will not be able to be delivered next year

when in other circumstances delivery would be expected. Note that

for this and for Options 1 and 2, the deferral of necessary projects in one

year invariably makes for more difficult budgeting and prioritisation decisions

in future years.

134. As with Option 2 above, this option

recognises the business-as-usual average rates increase at 3.9% and separately

recognises the beyond-business-as-usual impact of transport and urban planning

and delivery (1.5%) and water and wastewater planning and delivery (2.2%).

135. In addition, this option contributes a

combined 5% rate increase to debt retirement. This takes two forms.

Firstly, an additional direct contribution to the risk reserve of 2.5% as was

recommended in the December report. This starts to rebuild that

‘reserve’ which is currently showing a significant deficit.

136. Secondly a

contribution to the retirement of debt incurred where specific operating

expenditure has been funded (via Council resolution) by debt rather than

operating revenue in the year incurred. Examples of projects where

debt-funding could be replaced by rates funding (thereby repaying the debt

incurred) include:

(a) the Urban Form and Transport

Initiative and SmartGrowth costs

(b) the Tauranga System Plan for

transport

(c) the Te Papa intensification

project

(d) City Plan plan change projects

(e) Operational costs related to

transport network and asset management projects.

137. A 2.5% rates increase would remove the

debt associated with these projects.

138. As with Option 2, as currently proposed

this option provides for the existing operating budget but does not incorporate

additional operating expenditure relating to any of the ‘not yet

funded’ items listed earlier in this report. The inclusion of such

items would require separate resolution.

139. Overall, this option results in a total

rates increase of 12.6%.

140. This option, which enables capital

delivery (albeit at a minimum level needed to provide for growth and community

needs), maintains a 225% debt-to-revenue ratio, and provides a stepped increase

in revenue, is considered to be a minimally prudent

approach.

Option 4 – Prioritised capital expenditure plus debt

management

141. This option provides for full delivery of

the proposed and ‘for consideration’ capital programme and allows

for approximately $32 million of the $36 million of deferred projects to be

added back into the final budget. As such it is the option which does the

most in terms of providing a capital expenditure budget for 2020/21 to deliver

on the growth and community needs of the city.

142. This option creates a strong financial

base by paying down debt and markedly increasing revenue sources. This

sends a strong message to central government and regional and city partners that

the city, through the Council and its rating base, is prepared to contribute

significantly to addressing the fiscal situation.

143. This option builds on Option 3 with the

same 2.5% rates increase to accommodate the retirement of debt on the listed

operating projects which have been funded by debt. It also increases the

contribution to other debt retirement (be it into the risk reserve specifically

or into general debt retirement) by a further 5%.

144. Overall, this option provides for a 17.6%

rates increase.

145. As with Option 3, this option recognises

the need to deliver necessary capital projects while maintaining a prudent

debt-to-revenue ratio and providing a stepped increase in revenue. Option

4 is considered to be financially prudent and a strong position from which to

commence the Long-Term Plan planning and discussions with national and regional

partners.

Summary of options and recommendation

146. The table below identifies key financial

aspects of the four options provided.

|

Option

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

|

Basis

|

December resolution

|

Constrained capital investment

|

Prioritised capital investment plus limited debt

management

|

Prioritised capital investment plus debt management

|

|

Sustainable capex assuming $30m carryforward (at 225% D:R)

|

$149m

|

$158m

|

$188m

|

$214m

|

|

Capex projects capacity with a $20m

capital adjustment and accruals

|

$179m

|

$188m

|

$218m

|

$244m

|

|

Prioritised capex (included plus ‘for consideration)

|

$212m

|

$212m

|

$212m

|

$212m

|

|

Capex required to be removed from the

‘included’ and ‘for consideration’ lists

|

$33m

|

$24m

|

-

|

-

|

|

Capex that can be added back from the ‘deferred’ list

|

-

|

-

|

$6m

|

$32m

|

|

Impact on Operating Expenditure Budget

|

$4.3m of reductions to be agreed

|

Nil

|

Nil

|

Nil

|

|

Debt at year end

|

$661m

|

$671m

|

$691m

|

$709m

|

|

Debt-to-revenue ratio at year end

|

225%

|

225%

|

225%

|

225%

|

|

Total rates increase after growth

|

5.1%

|

7.6%

|

12.6%

|

17.6%

|

|

Median / mean residential rate increase

|

3.2%median

3.9% mean

|

5.7% median

6.6% mean

|

10.8% median

11.8% mean

|

14.9% median

16.1% mean

|

|

Debt management element of rates

|

nil

|

nil

|

5%

|

10%

|

147. It

is recommended that the Policy Committee approve an Annual Plan budget in the

mid to upper range of options 3 and 4. This is a prudent approach and

provides a pathway towards a more fiscally sustainable future.

Options analysis – increase rates only

148. Each of the above options includes a

combination of managing capital expenditure, managing debt, and increasing

revenue.

149. In preparing this report, a fifth option

was considered, that being to leave capital expenditure and debt as per the

original budget and to use rates increases as the only lever to effect

change. This is the ‘rate your way out of the problem’

approach.

150. This analysis showed that to service

known capital expenditure budgets, the necessary rates increases for the coming

years are as follows:

2020/21 –

17.6% (being the same as Option 4 above)

2021/22 –

26.8%

2022/23 onwards

– approx. 5%

151. Note that these calculations are based on

the expenditure budgets currently included in the planning system. There

are significant known (and likely to be even more significant

currently-unknown) increases to capital budgets in later years yet to be

included in that planning system.

152. This option is considered to be

unaffordable for the community and has not been pursued further.

Options analysis – rating model

153. During its 10 December meeting, Council

confirmed the final stage of the implementation of the changes to the rating

structure that were proposed through the 2018-28 Long-term Plan. These

involved a move to a uniform annual general charge (“UAGC”) of 15%

of total rating revenue (from 20% in the 2019/20 year) and a move to a

commercial differential of 1.2:1 (from 1.134:1 in the 2019/20 year).

154. Since that time, events outlined in this

report may result in the Committee wishing to reconsider the rating

model.

Matters to consider – UAGC

155. Tauranga has the highest UAGC of any metropolitan

local authority. This high UAGC disproportionately impacts on affordability for

ratepayers of lower value rating units (assuming that, broadly, rating

affordability is commensurate with property value, and accepting that this

isn’t always the case).

|

Local

Authority

|

Level of UAGC in the current year

|

|

Tauranga

City

|

$600

|

|

Hamilton

City

|

$348

|

|

Auckland

City

|

$424

|

|

Dunedin

City

|

No UAGC

|

|

Christchurch

City

|

$130

|

|

Wellington

City

|

No UAGC

|

156. The changes to wastewater budgets through

this Annual Plan process have resulted in the proposed wastewater uniform

annual charge (“UAC”) increasing by 10% from a 2019/20 base of $934

per property. As with the UAGC, the uniform nature of the wastewater UAC

means it has a disproportionate impact on affordability for ratepayers of lower

value rating units.

157. In effect, the 10% increase in the

wastewater UAC more than cancels out the gains for ratepayers of lower value

properties that were intended by Council when choosing to reduce the UAGC.

158. Under section 101(3)(b) of the Local

Government Act 2002, Council is required to consider the impacts of the

aggregate proposed funding sources in the Revenue and Financing Policy on the

community. Taken together, the aggregate impacts of the increased

wastewater UAC and the reduced-to-15% UAGC still have a negative effect on ratepayers

of lower valued properties.

Option R1 – Reconfirm the reduction in the UAGC from

20% to 15% of total rating revenue

159. This option reconfirms the decision made

in the 2018-28 Long-term Plan and confirmed by Council in December 2019.

Option R2 – Further reduce the UAGC from 20% to

10% of total rating revenue

160. This option changes the proposed rating

model to provide additional relief for ratepayers of lower valued

properties. This ensures that the principle of Council’s decision

through the 2018-28 Long-term Plan (that Council’s rating system should,

overall, be less regressive than was the case) is maintained despite the

significant increase to the wastewater UAC this year.

161. In contrast, ratepayers of higher valued

properties (both residential and commercial) will face an increased rating

burden.

162. The impact on some sample properties of

this proposal (compared to Option R1) are shown in the following tables:

|

Residential

rates impact

|

Option 1 Consistent with

December resolution

|

Option 2 Constrained

capital expenditure

|

Option 3 Prioritised

capex plus limited debt mgmt

|

Option 4 Prioritised

capex plus debt mgmt

|

|

Option R1 - UAGC 15%

|

Mean property (66%)

|

3.9%

|

6.6%

|

11.8%

|

16.1%

|

|

Median property (50%)

|

3.2%

|

5.7%

|

10.8%

|

14.9%

|

|

1st Quartile (25%)

|

2.1%

|

4.3%

|

9.1%

|

13.0%

|

|

Lowest residential (1%)

|

-0.1%

|

1.7%

|

6.1%

|

9.4%

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Option R2 - UAGC 10%

|

Mean property

(66%)

|

3.4%

|

6.0%

|

11.2%

|

15.5%

|

|

Median property

(50%)

|

1.8%

|

4.3%

|

9.3%

|

13.4%

|

|

1st Quartile (25%)

|

1.8%

|

1.6%

|

6.2%

|

10.0%

|

|

Lowest residential (1%)

|

-5.5%

|

-3.6%

|

0.4%

|

3.6%

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Commercial

rates impact

|

|

|

|

|

|

Option R1 - UAGC 15%

|

Mean property (66%)

|

12%

|

15%

|

20%

|

25%

|

|

Median property (50%)

|

10%

|

12%

|

17%

|

21%

|

|

1st Quartile (25%)

|

6%

|

8%

|

12%

|

15%

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Option R2 - UAGC 10%

|

Mean property (66%)

|

17%

|

20%

|

26%

|

30%

|

|

Median property

(50%)

|

12%

|

15%

|

19%

|

23%

|

|

1st Quartile (25%)

|

4%

|

6%

|

10%

|

13%

|

163. Option R2 is recommended.

164. It should be noted that the Long-term

Plan approach to progressively move the UAGC from the then level of 30% to 15%

was subject to a significant engagement and consultation exercise. If the

Committee accepts the above recommendation, a similar engagement and

consultation process should be considered.

Matters to consider –

commercial differential

165. As noted in paragraph 153, Council has

previously resolved to move the commercial differential to 1.2:1 (from

1.134:1 in the 2019/20 year). This is giving effect to the last

year of a three-year transition approved through the 2018/28 Long-term

Plan.

166. Staff recommendation is to undertake a

complete review of the rating model as part of the 2021/31 Long-term Plan

process. Matters to be assessed through such a review would be the extent

to which the proportionate benefits and costs to the commercial sector, compared

with the wider community, are reflected in the differential.

167. It is not recommended to amend the

commercial differential through this Annual Plan beyond that previously

consulted.

Statutory Context

168. In accordance with the Local Government

Act 2002 (“LGA”), Council is required to produce and adopt an

Annual Plan by 30 June 2020.

169. The purpose of this Annual Plan is to

identify variations from the financial statements of the third year of the

current Long-Term Plan.

170. Developing an Annual Plan requires

consultation on changes that are significantly or materially different from the

Long-Term Plan. If there are no such changes, Council is not required to

consult.

Consultation / Engagement

171. The matters considered within this report

and which, if recommendations are adopted, will be reflected in the draft

Annual Plan demand community input. It is therefore proposed that the

Annual Plan is presented to the community for consultation.

172. The proposed updates to the User Fees and

Charges and to the Development Contributions Policy will also require

consultation.

173. Consultation will take place between late

March and late April 2020. The respective consultation documents for the User

Fees and Charges and the Development Contributions Policy will require Council

approval in March.

Significance

174. Tauranga’s Significance and

Engagement Policy determines whether a matter is significant. In making the

assessment against this policy, there is no intention to assess the importance

of this item to individuals, groups, or agencies within the community and it is

acknowledged that all reports have a high degree of importance to those

affected by Council decisions. Materiality is defined in the LGA as being

something that would influence the decisions or assessments of those reading or

responding to the consultation document.

175. In terms of the Significance and

Engagement Policy the financial matters raised and the budget adjustments

identified and recommended through this report are deemed to be

significant. It is therefore proposed that the Annual Plan is presented

to the community for consultation.

Next Steps

176. Following Council’s decisions

relating to this report, staff will prepare the following documentation for

approval and adoption by the Policy Committee on 24 March 2020:

(a) Draft Annual Plan including

the financial supporting information

(b) Consultation document for the

Annual Plan

(c) Statement of proposal for the

User Fees and Charges

(d) Statement of proposal for the

Development Contributions policy.

Attachments

1. Capital diagram -

A11287211 ⇩

2. 2021 Annual Plan

Capex recommended to be prioritised in - A11287194 ⇩

3. 2021 Annual Plan

Capex New projects recommended to be prioritised in - A11287203 ⇩

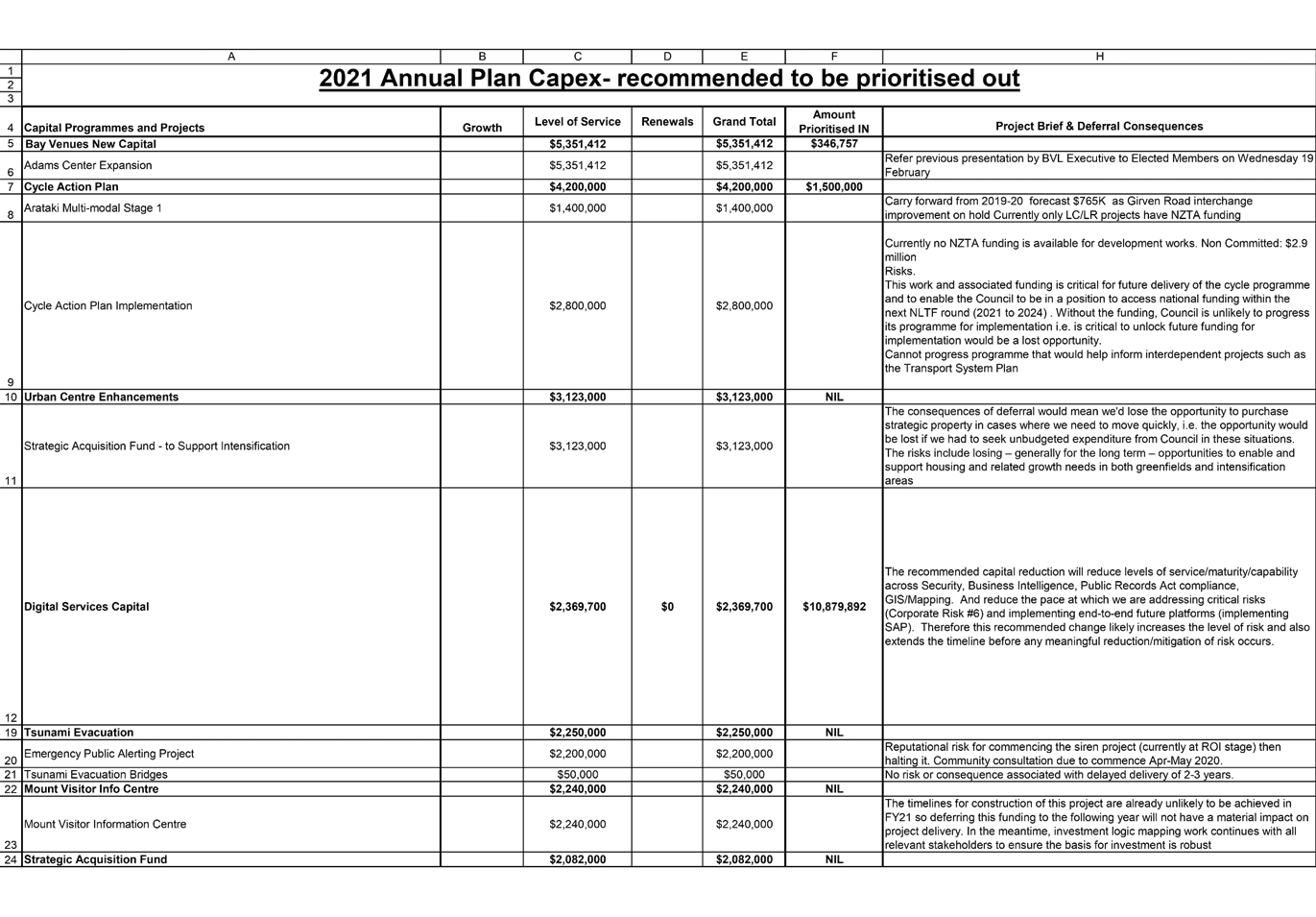

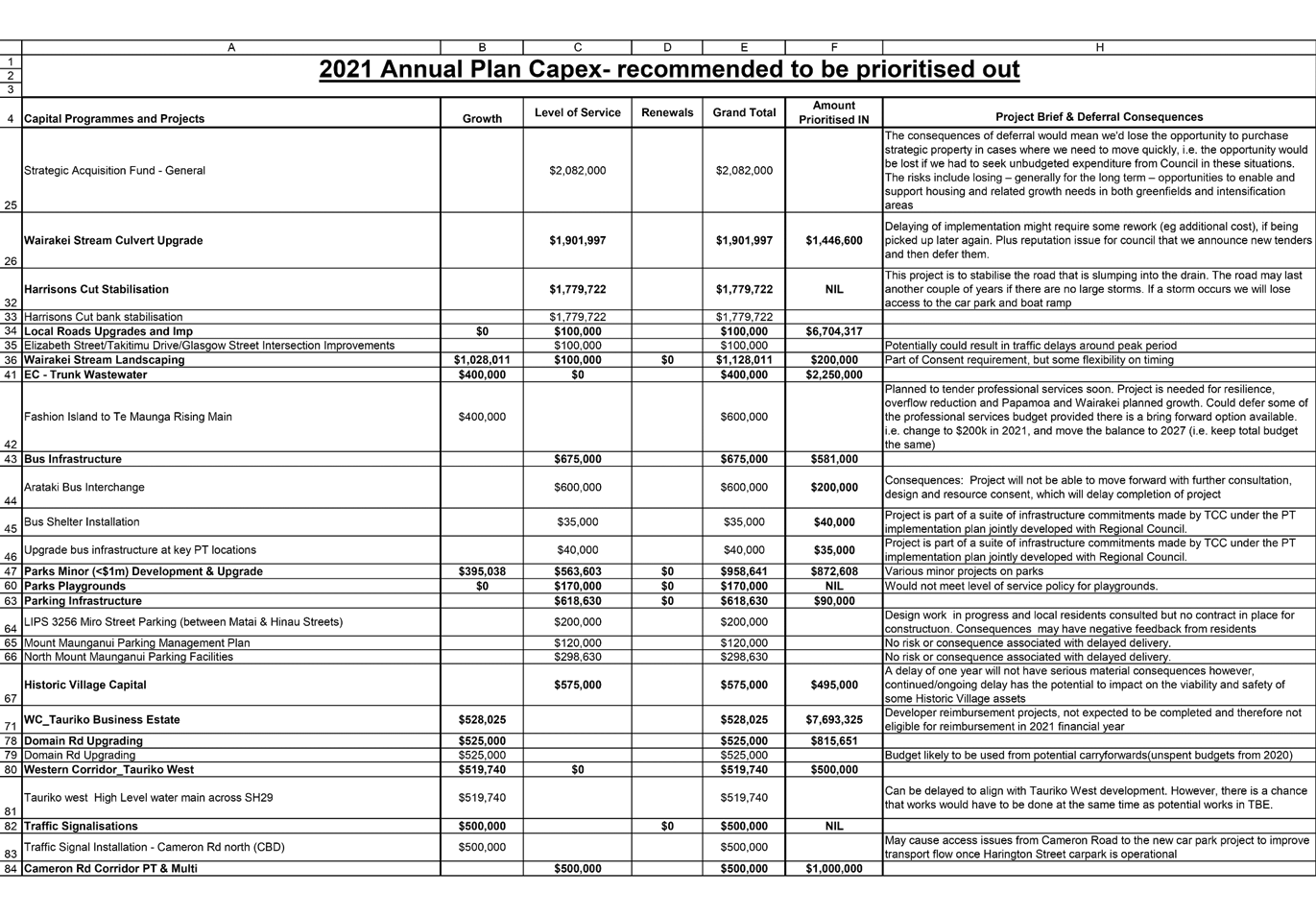

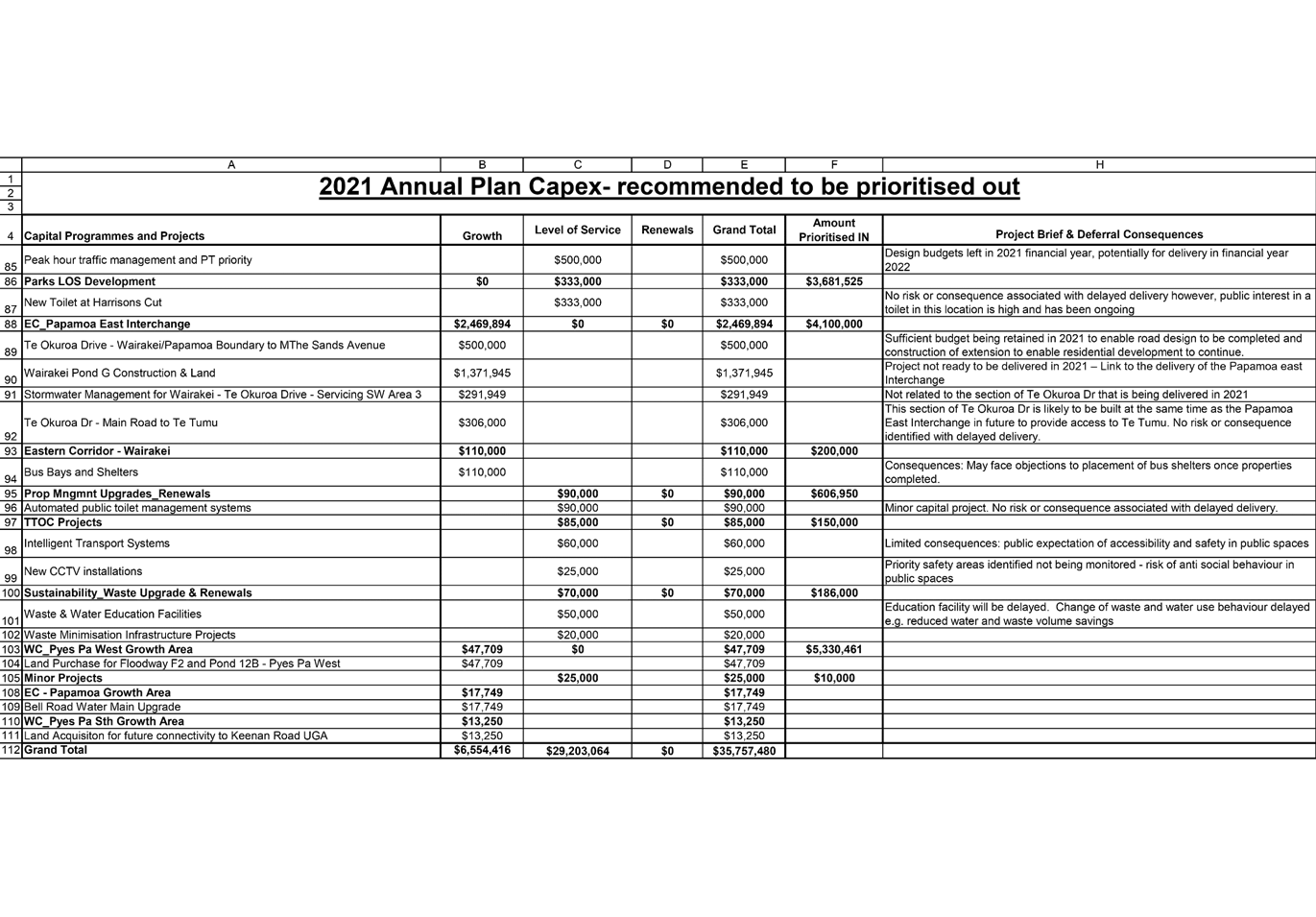

4. 2021 Annual Plan

Capex recommended to be prioritised out - A11287204 ⇩

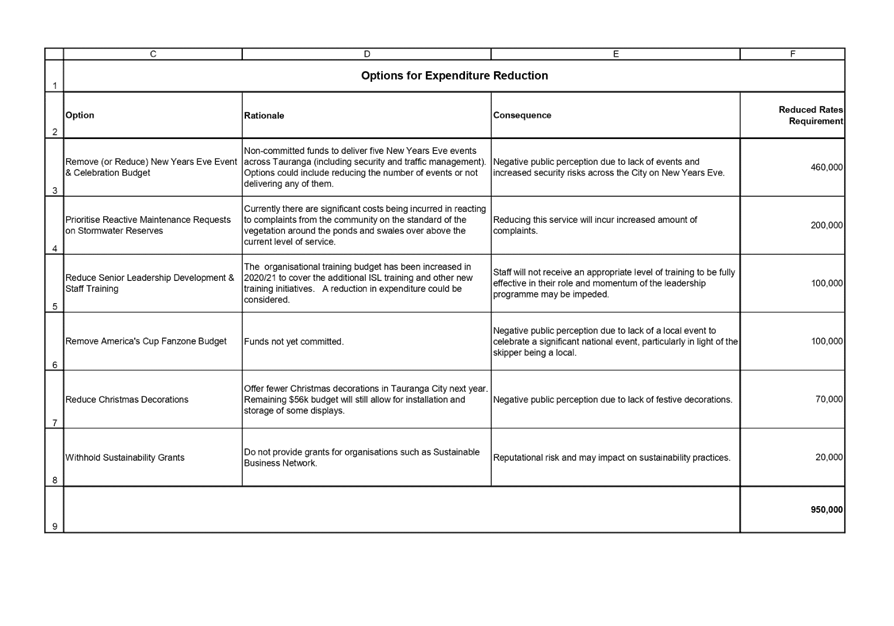

5. Opex Savings

Options - A11287189 ⇩