|

|

|

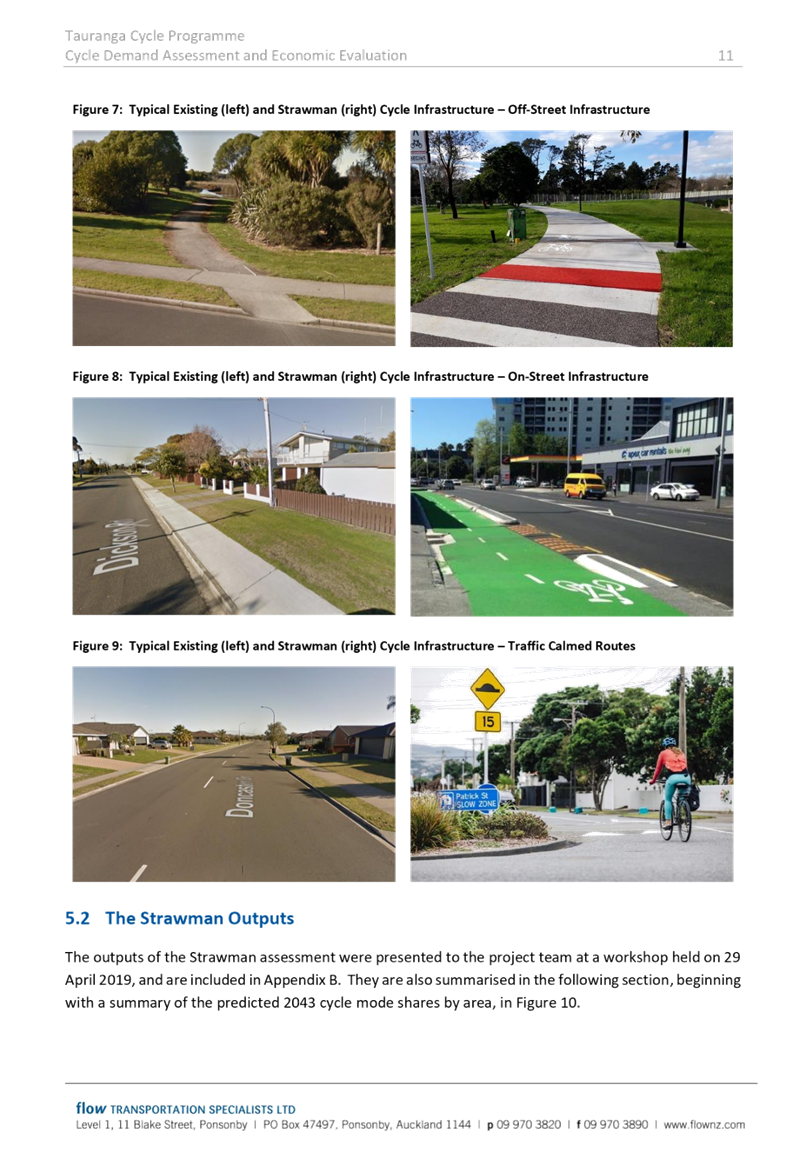

AGENDA

Ordinary Council Meeting

Tuesday, 5 May 2020

|

|

I hereby give notice that an Ordinary Meeting of

Council will be held on:

|

|

Date:

|

Tuesday, 5 May 2020

|

|

Time:

|

9am

|

|

Location:

|

Tauranga City Council

By video conference

|

|

Please

note that this meeting will be livestreamed and the recording will be

publicly available on Tauranga City Council's website: www.tauranga.govt.nz.

|

|

Marty Grenfell

Chief Executive

|

Terms of reference – Council

Membership

|

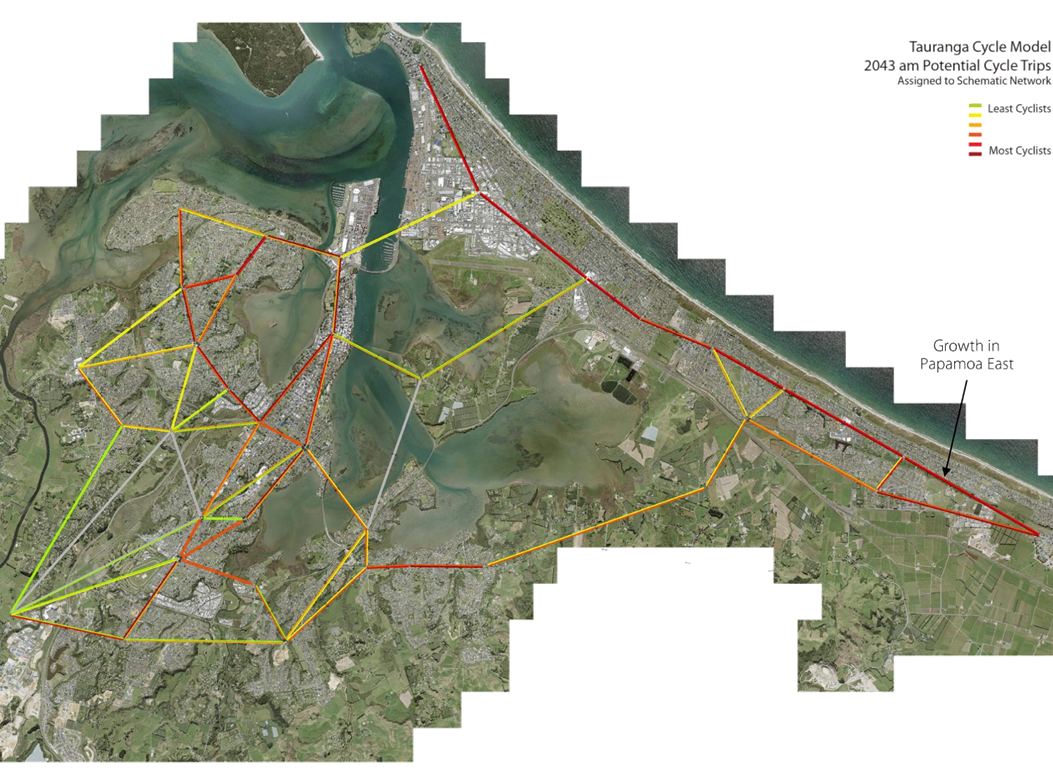

Chairperson

|

Mayor Tenby Powell

|

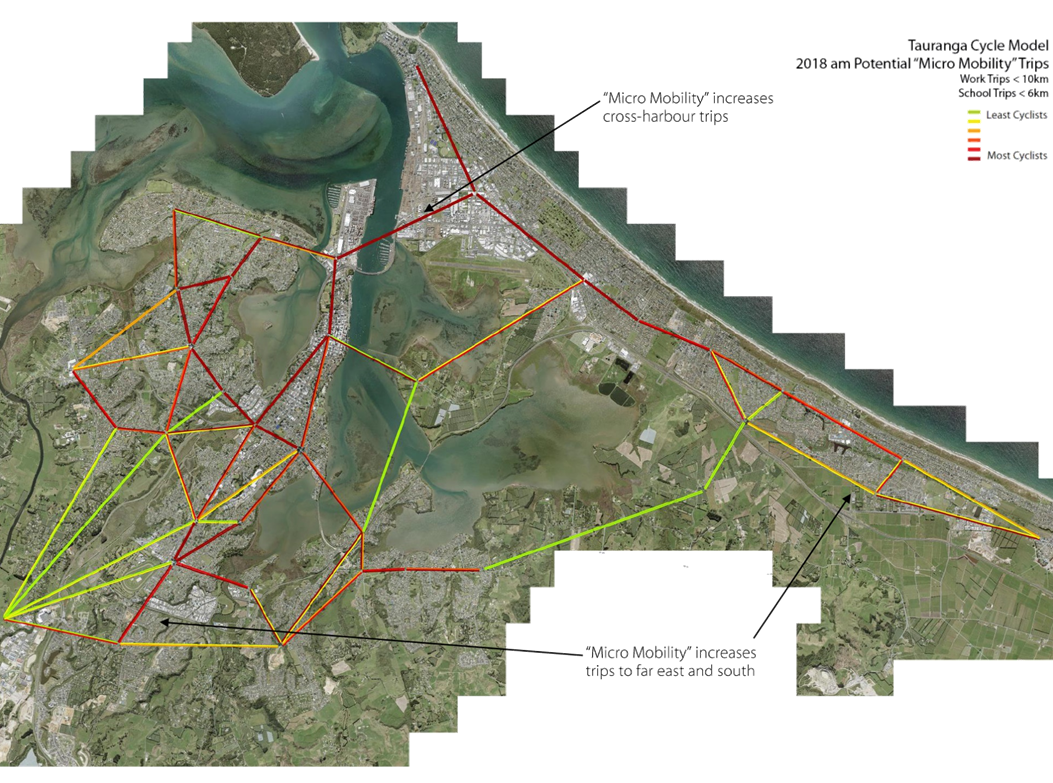

|

Deputy chairperson

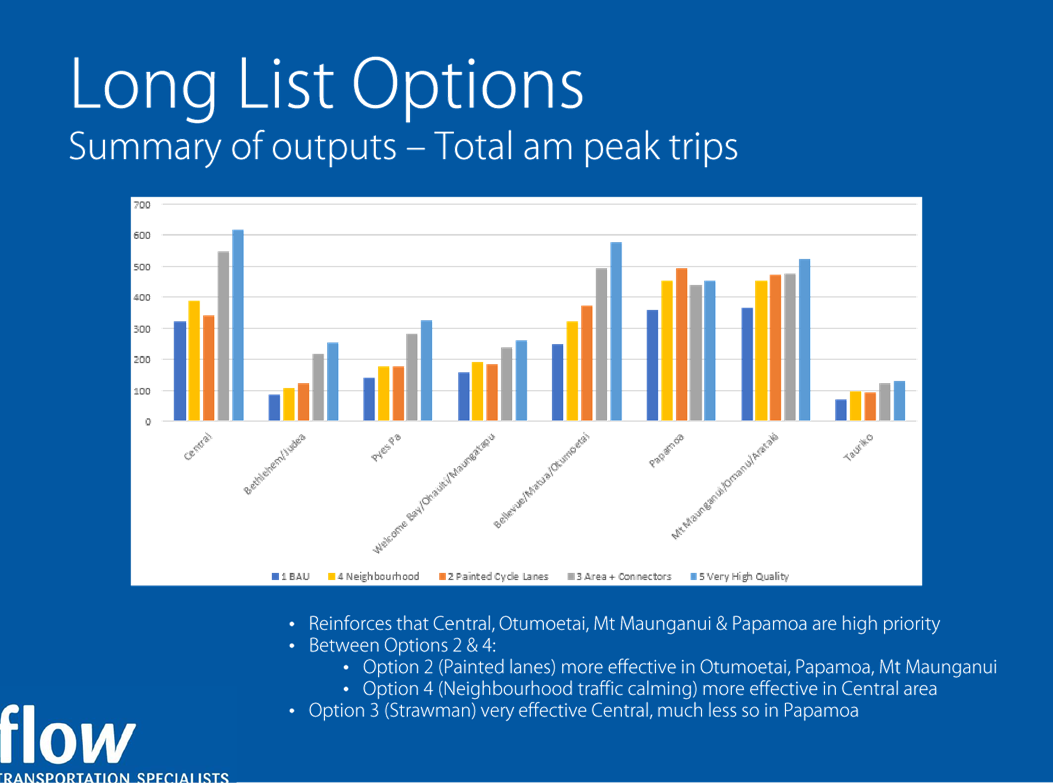

|

Cr Larry Baldock

|

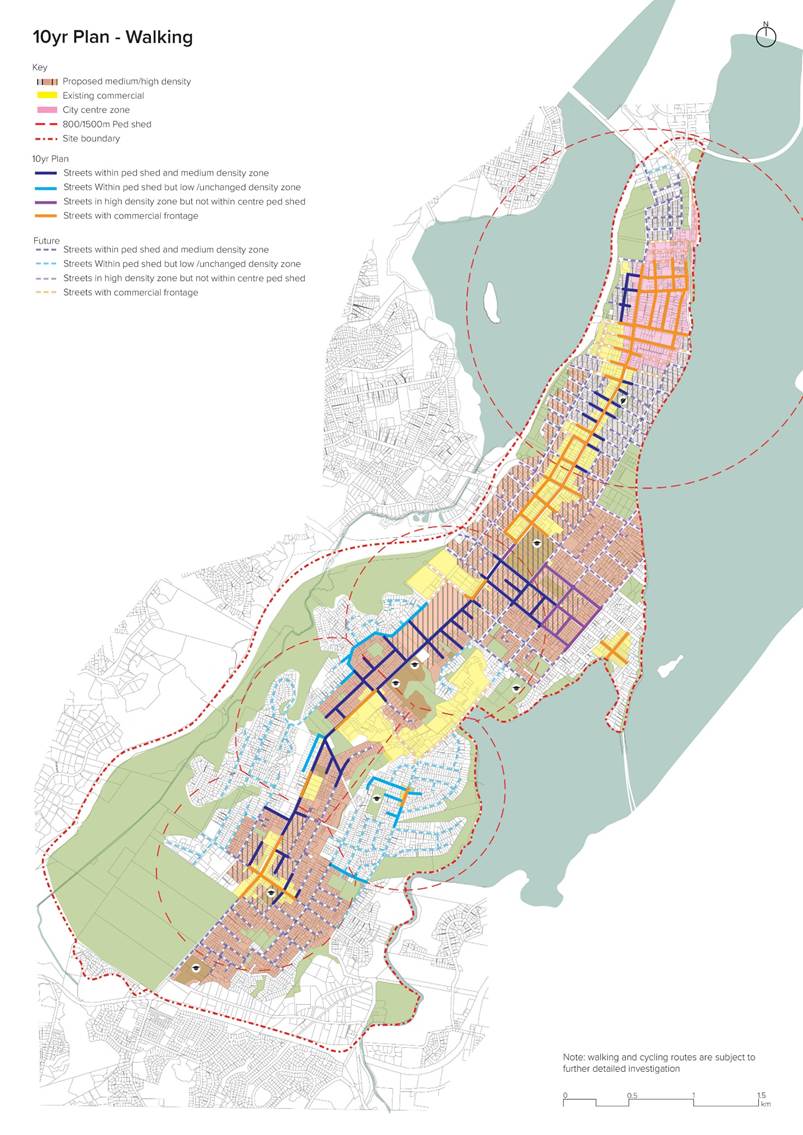

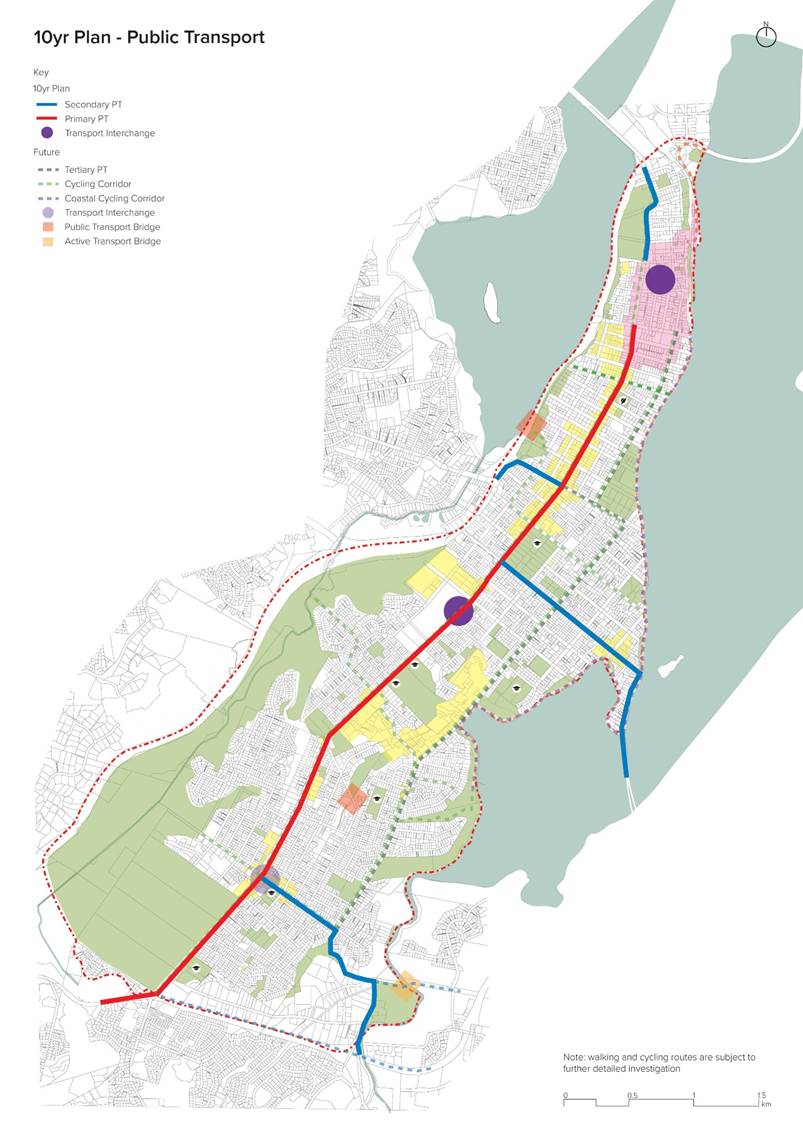

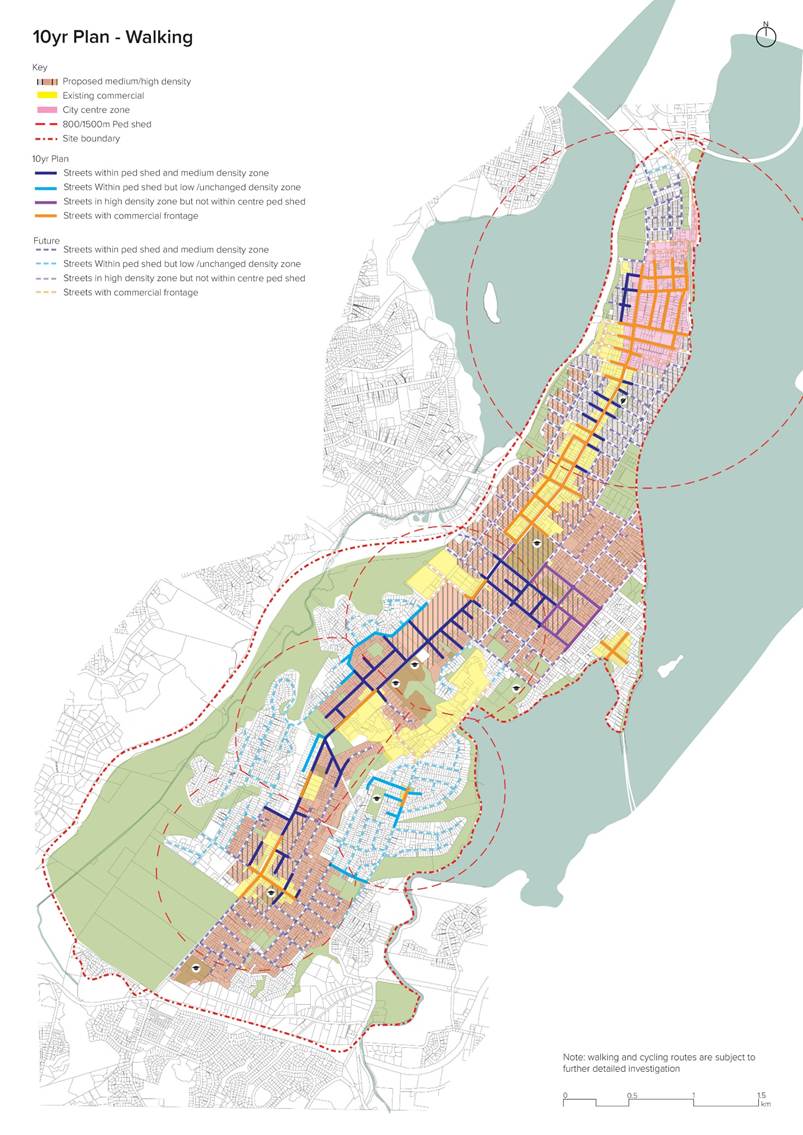

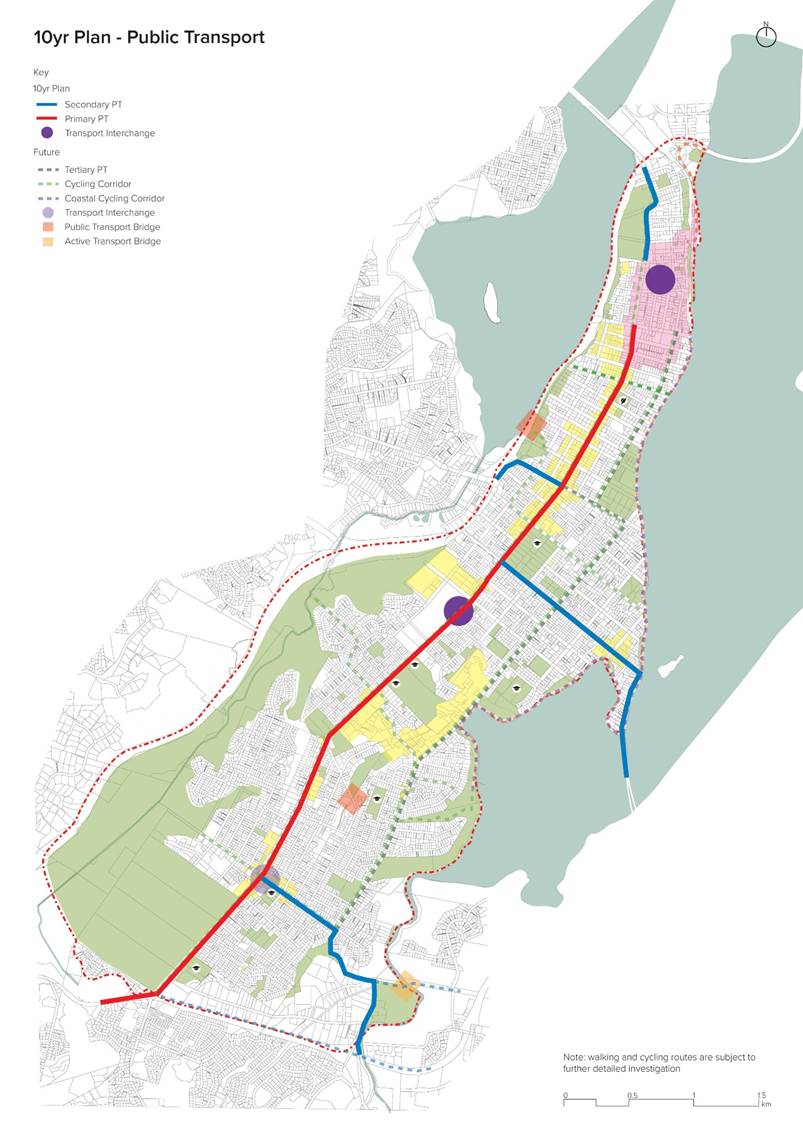

|

Members

|

Cr Jako Abrie

Cr Kelvin Clout

Cr Bill Grainger

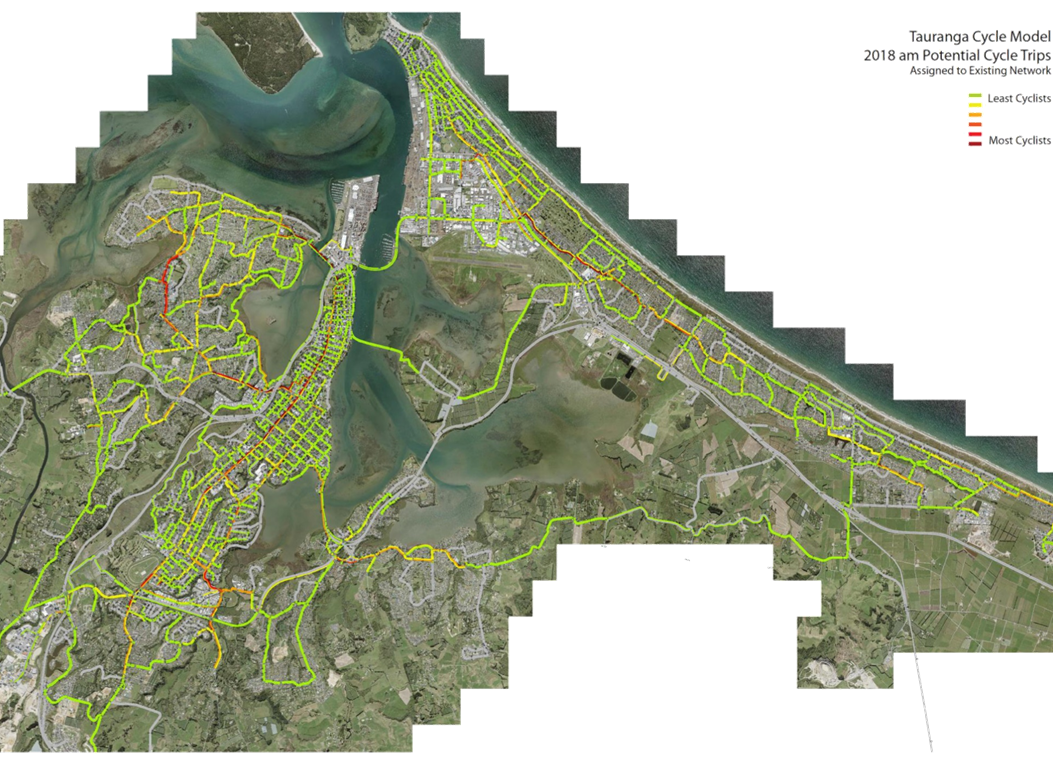

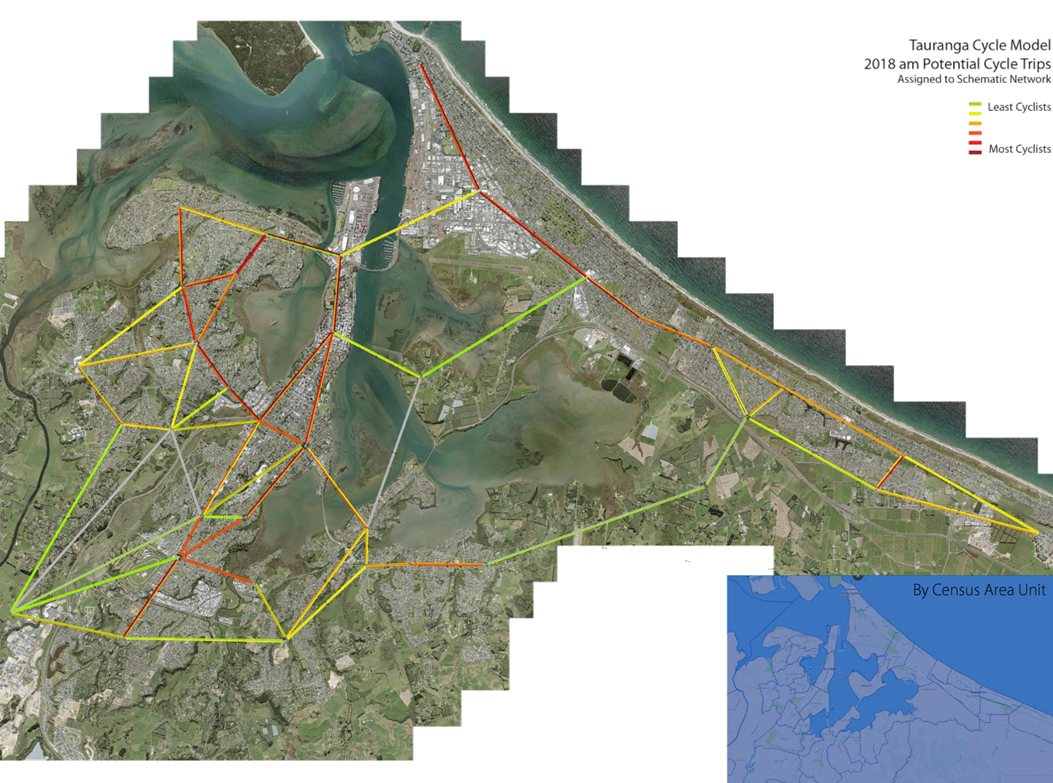

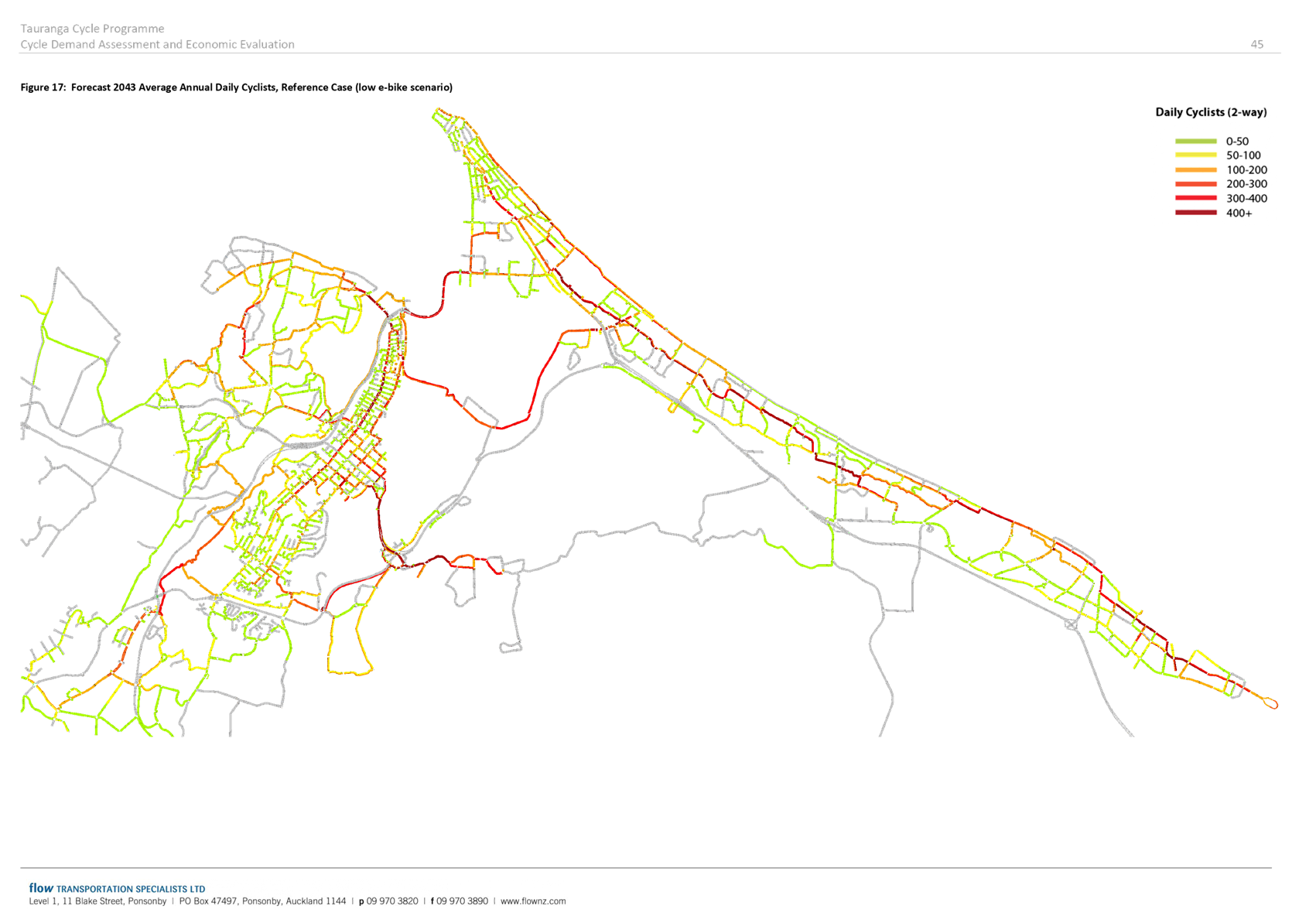

Cr Andrew Hollis

Cr Heidi Hughes

Cr Dawn Kiddie

Cr Steve Morris

|

|

Quorum

|

Half of the members physically present, where the

number of members (including vacancies) is even; and a majority

of the members physically present, where the number of members (including

vacancies) is odd.

|

|

Meeting

frequency

|

Six weekly or as required for Annual Plan, Long Term Plan

and other relevant legislative requirements.

|

Role

·

To ensure the effective and

efficient governance of the City

·

To enable leadership of the City

including advocacy and facilitation on behalf of the community.

Scope

·

Oversee the work of all

committees and subcommittees.

·

Exercise all non-delegable and

non-delegated functions and powers of the Council.

·

The powers Council is legally prohibited from delegating include:

o

Power to make a rate.

o

Power to make a bylaw.

o Power to borrow

money, or purchase or dispose of assets, other than in accordance with the

long-term plan.

o

Power to adopt a long-term plan, annual plan, or annual report

o

Power to appoint a chief executive.

o Power to adopt

policies required to be adopted and consulted on under the Local Government Act

2002 in association with the long-term plan or developed for the purpose of the

local governance statement.

o All final

decisions required to be made by resolution of the territorial

authority/Council pursuant to relevant legislation (for example: the approval

of the City Plan or City Plan changes as per section 34A Resource Management

Act 1991).

·

Council has chosen not to delegate the following:

o Power to

compulsorily acquire land under the Public Works Act 1981.

·

Make those decisions which are required by legislation to be made

by resolution of the local authority.

·

Authorise all expenditure not delegated to officers, Committees

or other subordinate decision-making bodies of Council.

·

Make appointments of members to the CCO Boards of

Directors/Trustees and representatives of Council to external organisations.

·

Consider any matters referred from any of the Standing or Special

Committees, Joint Committees, Chief Executive or General Managers.

Procedural matters

·

Delegation of Council powers to Council’s committees and

other subordinate decision-making bodies.

·

Adoption of Standing Orders.

·

Receipt of Joint Committee minutes.

·

Approval of Special Orders.

·

Employment of Chief Executive.

·

Other Delegations of Council’s powers, duties and

responsibilities.

Regulatory matters

Administration,

monitoring and enforcement of all regulatory matters that have not otherwise

been delegated or that are referred to Council for determination (by a

committee, subordinate decision-making body, Chief Executive or relevant

General Manager).

10 Business

10.1 Te

Papa Indicative Business Case

File

Number: A11387270

Author: Carl

Lucca, Programme Director: Urban Communities

Authoriser: Christine

Jones, General Manager: Strategy & Growth

Purpose of the Report

1. To

provide the Council an update on the Te Papa Indicative Business Case process

and seek approval to submit the Business Case to the New Zealand Transport

Agency (NZTA) for Approval in May 2020.

|

Recommendations

That the Council:

(a) Endorses

the recommended Te Papa peninsula urban form option.

(b) Agrees

in principle to the Te Papa peninsula 30-year multi-modal transport programme

to support the recommended urban form option, subject to further

investigation and funding availability

(c) Approves

the Te Papa Indicative Business Case be submitted to New Zealand Transport

Agency for consideration and approval in May 2020.

(d) Notes

that investment timing, costs and cost sharing are subject to further

investigations and agreement between the project partners and will come

before Council for approvals as the programme progresses.

|

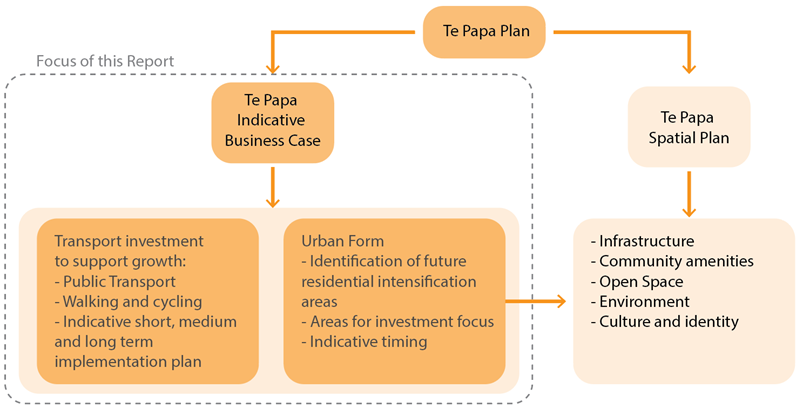

Executive Summary

2. The

Te Papa project is made up of two core deliverables – the Te Papa Spatial

Plan, and the Te Papa Indicative Business Case (IBC). This report focuses on

the Indicative Business Case, including:

(a) An

overview of the options considered

(b) The

recommended ‘preferred way forward’ for urban form and the

supporting multi-modal transport programme

(c) A

detailed summary of the recommended multi-modal transport programme, including

indicative timing

(d) A

summary of potential benefits accruing from the recommended urban form and

multi-modal transport programme.

3. The

Te Papa IBC has been prepared by Tauranga City Council (TCC) in partnership

with NZTA and Bay of Plenty Regional Council. The IBC recommends an integrated

land use transport strategy that will increase opportunity for higher density

living in close proximity to centres, public transport and other amenities

along the Te Papa peninsula, supported by a sustained, balanced investment

programme in active modes and public transport infrastructure.

4. As

outlined on the NZ Treasury’s website, an Indicative Business Case

provides decision makers with an early indication of the preferred way forward

for high value and/or high risk investment proposals. It outlines how the

proposed investment fits within the organisation(s) strategic intentions;

confirms the need for investment and the case for change; and recommends an

indicative or preferred way forward for further development… The

information presented is indicative only. It provides the decision-makers

with just enough information to consider change and confirm the options being

considered, and an early opportunity to make a decision before too much work is

done.

5. Having

regard to the above, the purpose of the Te Papa IBC is to set in place an

agreed land use transport strategy that will form the basis for ongoing

collaboration between Tauranga City Council, Regional Council and central

government agencies to deliver an agreed vision for the Te Papa peninsula in

Tauranga City. Commitment to funding, timing and cost sharing will be subject

to more detailed planning which will come before Council for approvals as the

programme progresses.

6. The

scale of growth required in Te Papa and the wider city means significant

further investment in movement networks is needed. Relative to the

recommended way forward, a basic investment package (i.e. the do minimum

option) sufficient to ‘just keep pace’ with Te Papa peninsula and

wider regional growth pressures and safety management issues will not

go far enough to deliver appropriate transport levels of service as the

population grows; nor will it avoid sufficiently avoid compounding land use

related liabilities and inefficiencies for travel time, housing affordability,

health outcomes, liveability or sustainability.

7. The

IBC assessment and recommendations recognise Te Papa peninsula as a central

element within the wider urban system of Tauranga City and the Western Bay of

Plenty. To unlock more than $1billion of community benefits for Te Papa

peninsula and the wider region, multi-modal transport investments in the order

of $450m are required over the next 30 years.

8. In

this regard, and taking into account wider investment that will be required in

infrastructure and community amenities, the indicative benefit cost ratio (BCR)

associated with the recommended urban form and multi-modal transport programme

is estimated to be between 1.5:1 and 2:1.

9. The

urban form and multi-modal transport programme recommended will result in far

more holistic benefits for the city and community than other options

considered, including:

(a) Better

and more equitable access to social and economic opportunities

(b) Housing

that meets our needs

(c) More

opportunities for meaningful employment and economic growth in Te Papa

(d) Neighbourhoods

that are more liveable and have a stronger sense of culture and identity

(e) Improvements

in environmental quality.

10. In

this regard, the IBC will deliver an integrated land use transport strategy

that is well aligned with central government policy, as well as local strategic

direction for growth. This will also greatly assist in leveraging

government investment in other parts of our city such as in Tauriko.

11. Complex

interventions where there is a high level of risk and/or uncertainty will be

identified as requiring further work to be undertaken, such as a Detailed

Business Case phase. Fast tracking of standard interventions that are

relatively low risk will also be enabled by the IBC. These interventions will

be derived from existing evidence base (e.g. other business cases) where the

evidence and justification for the intervention and standard interventions has

already been established.

12. Importantly,

the IBC also supports Council’s response to Covid-19 crisis. TCC is

working closely with central government to determine potential stimulus

packages, including ‘shovel ready’ Crown Infrastructure Projects

(CIPs), and short term (0-10year) projects. The Te Papa IBC forms part of the

evidence base to move forward a number of these projects, including the Cameron

Road Multi-modal Stage 1 project and other transport, infrastructure and

community projects that will benefit the city and community.

13. The

timing of urban growth and transport investment recommended within the IBC

acknowledges the integrated land use transport approach – with growth

numbers over time supporting public transport investment, and also

acknowledging that walking, cycling and public transport offer a value

proposition that will attract people to live in the area as well as making it

safer and providing a wider range of other benefits. Accordingly, enabling a

number of growth projects is recommended (e.g. Gate Pa regeneration) to assist

in catalysing / bringing forward the viability of public transport in

particular (with benefits for Te Papa and the wider city); while timing of

transport investment includes consistent and ongoing investment in walking and

cycling, and public transport investment in line with but slightly ahead of

projected population growth.

Background

14. This

section provides an overview of the Te Papa IBC and builds on previous reports

relating to the Te Papa project.

Overview

of the Indicative Business Case

15. The

Te Papa project is made up of two core deliverables – the Te Papa Spatial

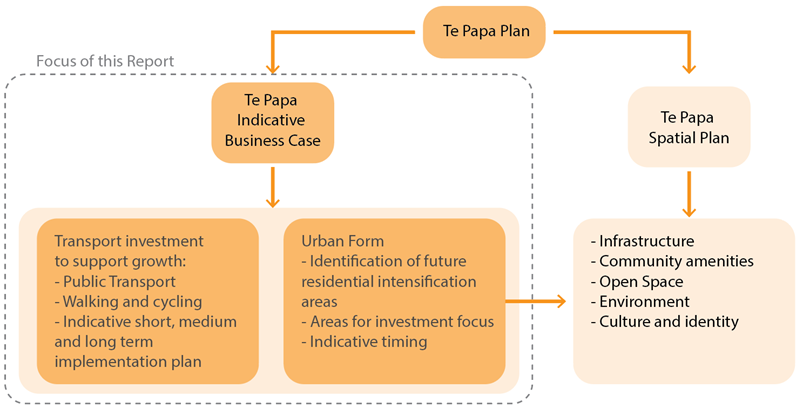

Plan, and the Te Papa IBC (refer Figure 1 below). This report focuses the

business case process and outcomes.

Figure

1: Te Papa project – Indicative Business Case and Spatial Plan Components

16. While

the IBC focuses on an integrated land use transport strategy, it will also be

supported by the broader Te Papa Spatial Plan, which provides for consideration

of supporting infrastructure (including 3-waters) and community investment,

including community amenities, opens space, environmental, cultural and wider

considerations. The Spatial Plan ‘Outcomes and Ideas’ Discussion

Document is currently out for engagement (refer

https://www.tauranga.govt.nz/our-future/projects/te-papa-peninsula), and the

draft spatial plan will be brought before Council June this year. This will

include associated infrastructure and community investment options to support

growth, for Council’s consideration.

17. TCC

is working with partners including NZTA, Regional Council and Mana whenua to

progress both the spatial plan and business case, as well as liaising closely

with other central government agencies and key stakeholders including

Kāinga Ora, Ministry of Housing and Urban Development and Accessible

Properties Limited.

18. The

recommended urban form and multi-modal transport programme promotes an

integrated land use transport strategy that has the potential to unlock more

than $1billion of community benefits for Te Papa peninsula and the wider

region, as well as wider benefits for the city, including:

(a) Better

and more equitable access to social and economic opportunities

(b) Housing

that meets our needs

(c) More

opportunities for meaningful employment and economic growth in Te Papa

(d) Neighbourhoods

that are more liveable and have a stronger sense of culture and identity

(e) Improvements

in environmental quality.

A full outline of the potential

IBC benefits is included within Attachment 4 to this report.

19. A

full copy of the Te Papa Indicative Business Case summary is included as Attachment

1.

Strategic / Statutory Context

Central

Government Direction on Growth

20. The

IBC seeks to deliver an integrated land use transport strategy that is well

aligned with central government policy, including the Urban Growth Agenda,

NZTA’s Arataki Strategy, the Government Policy Statement on Transport and

the draft National Policy Statement on Urban Development (NPS-UD). In addition,

it aligns with local strategic direction, including the draft Tauranga Urban

Strategy, Future Development Strategy and Urban Form and Transport Initiative.

21. The

draft NPS-UD, released in September 2019, stresses the urgency for urban growth

areas in New Zealand to grow both up and out, and for district plan

rules to become more enabling of intensification. The government has identified

Tauranga as a ‘major urban centre’ which will need to meet more

stringent growth requirements to be reflected in Tauranga’s planning

rules. The NPS-UD identifies a number of options in relation to density

requirements in close proximity to centres and public transport. These options

place emphasis on providing densities of 60 dwellings per hectare within

walking distance of these amenities.

22. As

outlined NPS-UD, when cities work well they provide a range of benefits for

their residents, the economy and the environment, including:

· Maximising

opportunities for people to interact, socially and economically

· Supporting

a more diverse and productive economy by bringing together people with varied

and complementary knowledge and skills

· Contributing

to the well-being of residents and raise living standards for all.

23. Key

contributing factors to these outcomes include:

· Enough

housing and business space, including housing choices that let people live

affordably close to the places they need to travel

· A

transport system that allows for the effective and efficient movement of people

and goods, and promotes safe, healthy and active lifestyles.

24. In

December 2019, NZTA released its Arataki 10-year Strategy. The Arataki Strategy

links strongly with the NPS-UD, providing direction on steps required to

achieve the government’s short-term priorities and longer-term outcomes,

including:

(a) Improve

urban form – use transport to improve connections between people, product

and places

(b) Transform

urban mobility – shift from our reliance on single occupancy vehicles to

more sustainable transport solutions for the movement of people and freight

25. The

integrated land use transport strategy recommended by the Te Papa IBC is well

aligned with above direction.

Strategic

Context

26. It

is recognised that this project has much broader benefits beyond the Te Papa

peninsula. Cameron Road forms the key public transport spine to the

western corridor (Pyes Pa / Tauriko area) where significant greenfield urban

development in underway and planned. Investment in Cameron Road is

required to deliver a high-quality public transport level of service for the western

corridor in order to achieve a high public transport mode share instead of

continued reliance of private vehicle travel. The proposed urban form approach

and supporting multi-modal transport programme for Te Papa will assist in

leveraging government investment in other parts of our city such as in Tauriko.

27. In

addition, the government is investing close to $1billion in the Tauranga

Northern Link and 4-laning to Omokoroa north of Tauranga. This includes managed

lanes with priority for buses and high occupancy vehicles. These transport

projects will connect to Cameron Road. As such, to provide a high quality and

seamless experience for public transport that encourages the use of public

transport these proposed improvements to Cameron Road are essential.

Consistency

with Current Council Priorities

28. Importantly,

the IBC also supports Council’s response to Covid-19 crisis. TCC is

working closely with central government to determine potential stimulus

packages, including ‘shovel ready’ Crown Infrastructure Projects

(CIPs), and short term (0-10year) projects. The Te Papa IBC forms part of the

evidence base to move forward a number of these projects, including the Cameron

Road Multi-modal Stage 1 project and other transport, infrastructure and community

projects that will benefit the city and community.

Options Analysis

29. This section provides a summary of Te

Papa IBC options considered, including:

(a) Overview

of the options and the recommended ‘preferred way forward’ for

urban form and the supporting multi-modal transport programme

(b) A

detailed summary of the recommended multi-modal transport programme, including

timing

(c) A

summary of potential benefits and outcomes accruing from the combined urban

form and multi-modal transport programme.

Overview

of the options and the recommended ‘preferred way forward’

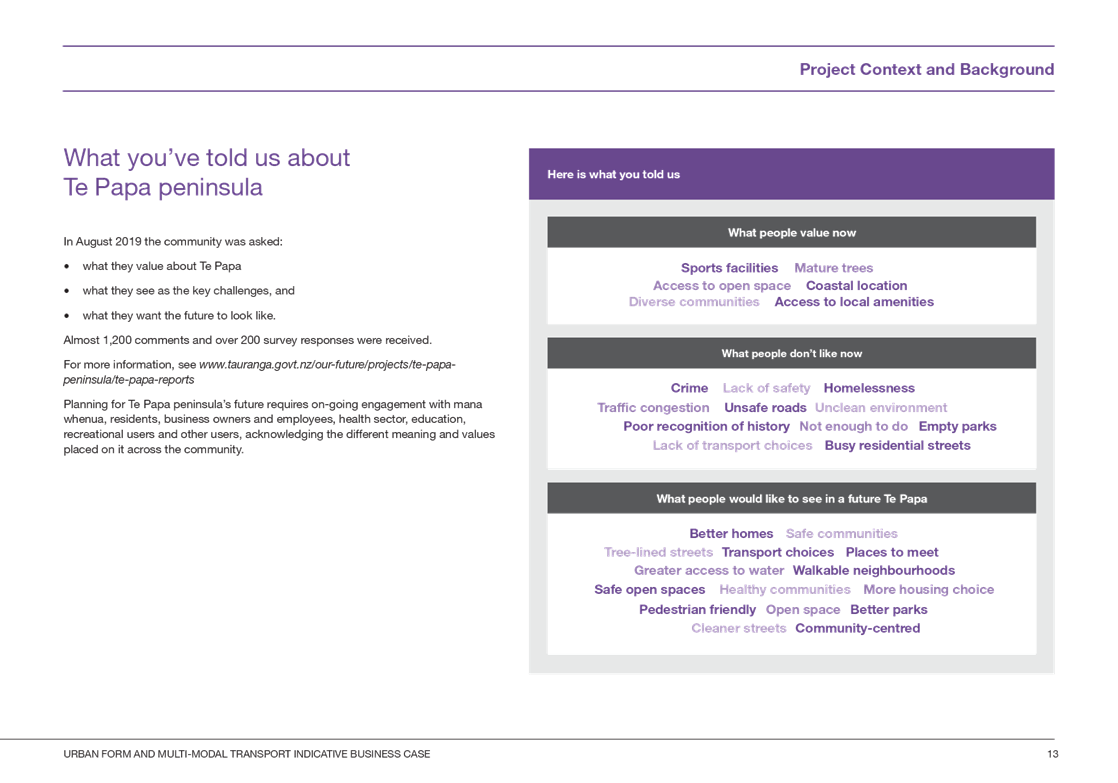

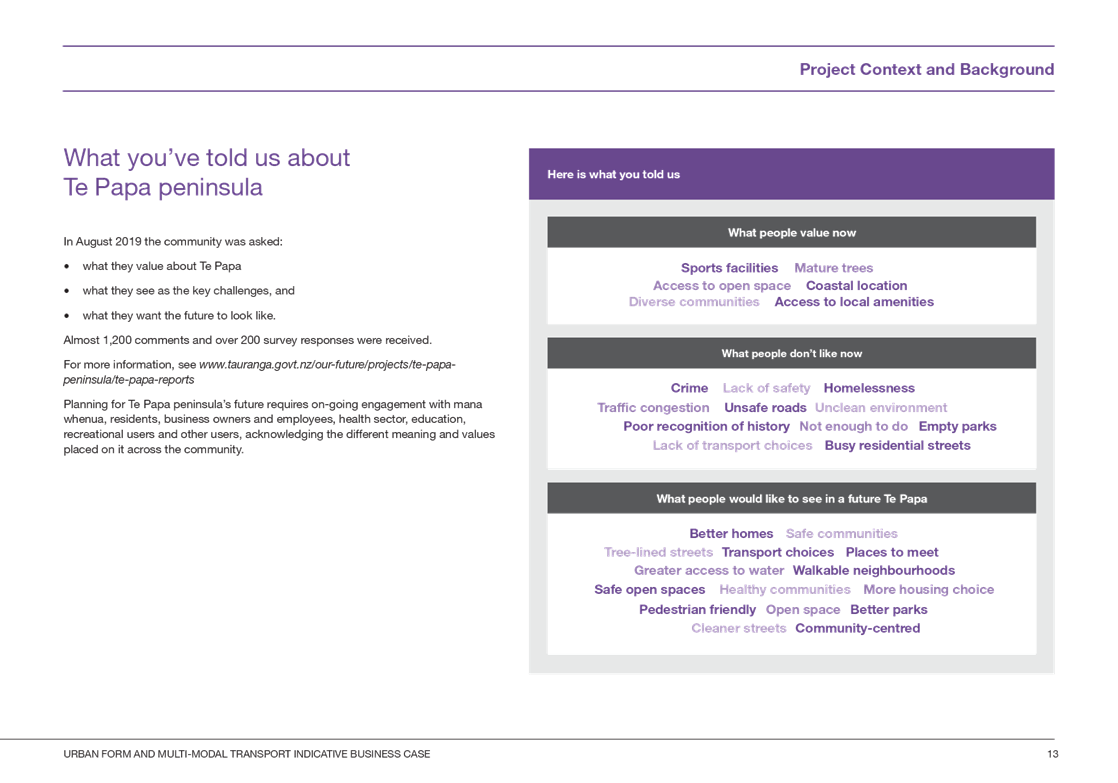

30. The

outcomes of the Te Papa analysis, community ‘values’ engagement,

Investment Logic Mapping and design sprint were used to inform the preparation

of options for the urban form and supporting transport assessment that

followed, undertaken through a two-part process:

(a) Step

1: Option refinement and assessment for urban form (land use); and

(b) Step

2: Option preparation and assessment for strategic transport interventions to

support the proposed urban form and wider city outcomes.

31. The

option assessment for each step was undertaken through a series of workshops

(option development; option assessment; assessment review) including relevant

technical experts from TCC, Regional Council and NZTA.

32. The

urban form assessment was assessed against the following criteria:

(a) Project

Investment Objectives (100% of the assessment criteria):

(i) The

built environment will reflect Te Papa’s culture, heritage and identity

(ii) The

quality of public life and use of public realm will continuedly improve across

Te Papa's neighbourhoods

(iii) Environmental

quality across Te Papa will improve by 2050

(iv) Average

density of 30 dwellings per hectare across Te Papa, with higher densities in

close proximity to centres and public transport by 2050

(v) Employment

numbers across Te Papa will increase by 50-60% by 2050

(vi) Walking,

cycling, and public transport will represent 40% of all travel movements within

Te Papa, and 25% of all travel movements into and out of Te Papa, by 2050

(b) Feasibility

(sensitivity testing) e.g. consentability, safety and design, operational and

financial

33. The

transport assessment was assessed against the following criteria:

(a) Project

Investment Objectives (60%), as outlined above

(b) Implementability

(20%), e.g. consentability, safety and design, operational and financial

(c) Assessment

of Effects (20%), e.g. effects in relation to safety, cultural, built

environment, social, property.

Urban

Form Options Considered and Preferred Way Forward

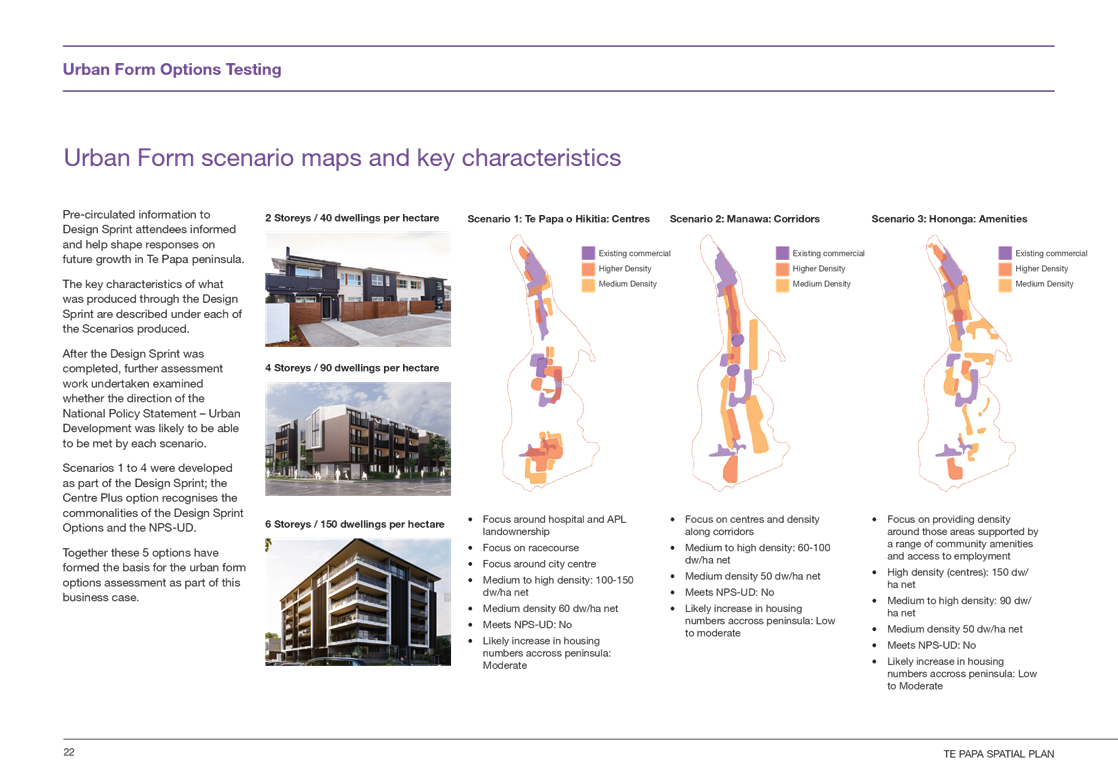

34. Five

urban form options were derived from the design sprint process, while also

taking into account national direction on urban form. The options considered

are summarised below.

35. Option

5 – ‘Centres Plus’ was assessed as the preferred way forward.

Attachment 2 contains the Urban Form Preferred Way Forward Plan.

|

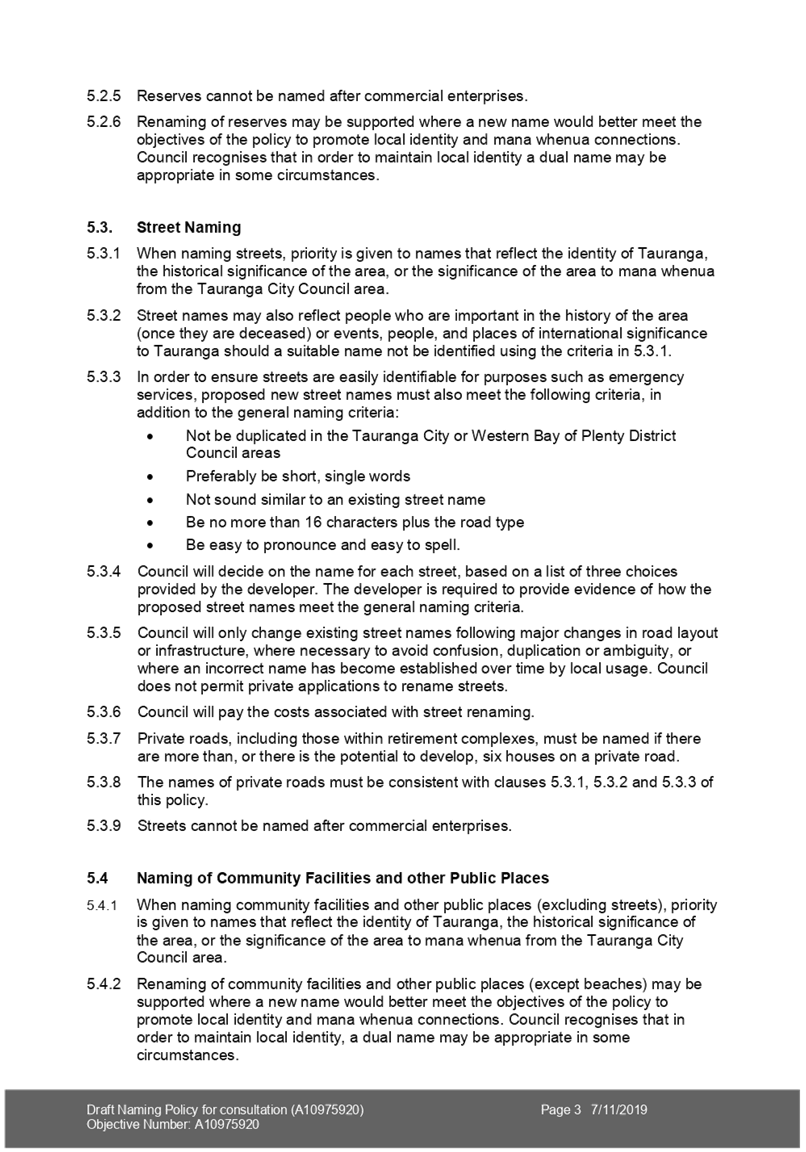

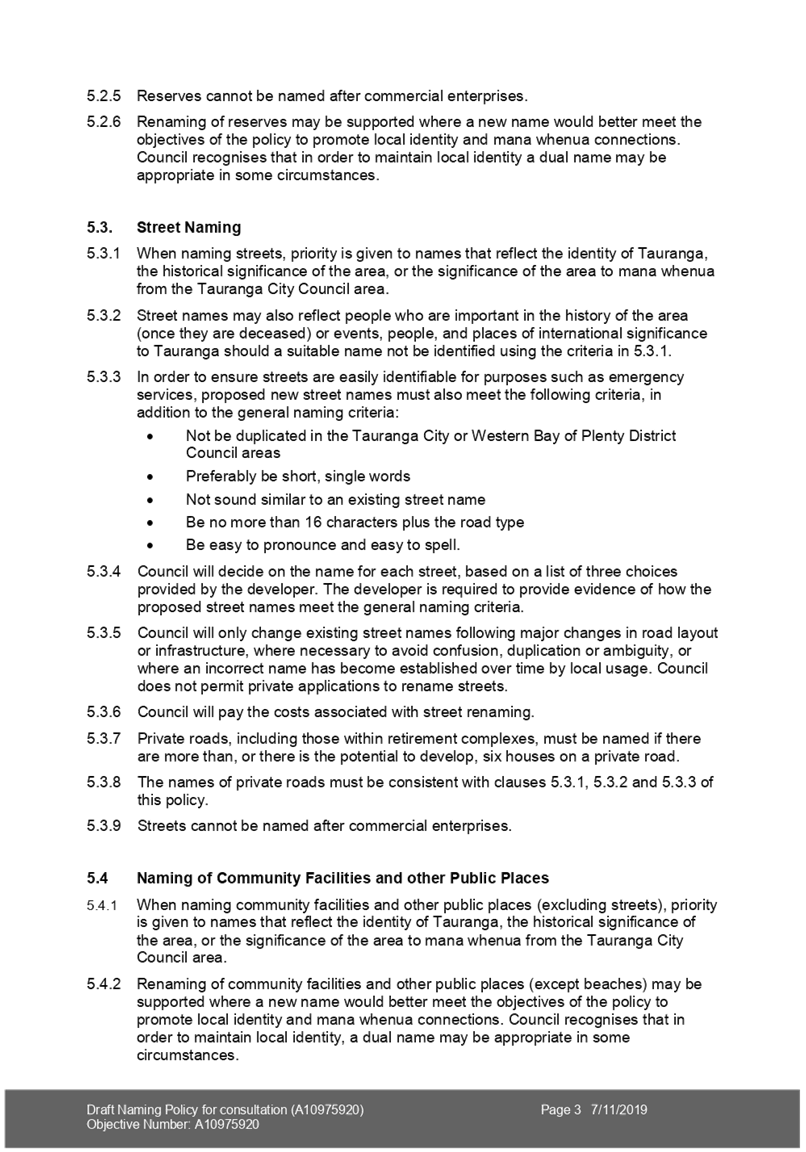

Option

|

Description

|

|

Option 1 –

Centres approach

|

Centres based urban

form focused on higher densities in close proximity to the city centres and

neighbourhood centres.

Meets NPS-UD: No

Likely increase in

housing numbers across peninsula: Moderate

|

|

Option 2 –

Corridors approach

|

Corridors based urban

form focused on higher densities in close proximity to public transport

routes

Meets NPS-UD: No

Likely increase in

housing numbers across peninsula: Low to moderate

|

|

Option 3 –

Dispersed approach

|

Dispersed urban form

focusing on higher densities distributed in relation to access to open space,

schools and other amenities

Meets NPS-UD: No

Likely increase in

housing numbers across peninsula: Low to moderate

|

|

Option 4 – Design

sprint mixed approach

|

A mixed group scenario,

taking learnings from the first three scenarios over the first two days,

which resulted in a largely centres / corridors-based approach.

Meets NPS-UD: No

Likely increase in

housing numbers across peninsula: Low to moderate

|

|

Option 5 –

Centres ‘Plus’ (preferred way forward)

|

A refined medium

density residential land use pattern that builds on the strengths and

commonalities of the design sprint (particularly as they relate to a focus on

centres), including:

· ‘Heat

mapping’ those areas of the four design sprint scenarios identified as

appropriate for medium density residential, recognising the ‘broad

brush’ approach to line on maps used at the design sprint

· Consideration

of the draft National Policy Statement for Urban Development, which

identifies the need for greater densities in proximity to centres, corridors

(public transport) and amenities

· Consideration

of the above matters in light of residential intensification

‘suitability mapping’, including walking distances from centres,

corridors and other amenities

Meets NPS-UD: Yes

Likely increase in

housing numbers across peninsula: High

|

36. Supported by the proposed

transport interventions, wider interventions promoted within the Spatial Plan

and Plan Change 26 – Housing Choice, over the next 30 years, the Centres

‘Plus’ option will:

(a) Provide opportunity for

more houses close to centres and public transport, providing a range of housing

types and allowing more people to walk to where they want to go, in line with

central government policy for urban development. This includes:

(i) Higher residential

densities in close proximity of city centre, Gate Pa / Hospital and Greerton

and with good access to a range of amenities, providing for up to 150 dw/ha net

(4-6 storeys in height)

(ii) Medium residential

densities within areas walking distance to centres and other amenities: 90

dw/ha net (4 storeys in height)

(iii) Opportunity for up to

19,400 new homes and 29,300 new residents.

(b) Provide significant

opportunity for employment growth, with up to 14,000 - 15,000 (50-60%)

additional employees across the peninsula

(c) Provide ongoing community

and infrastructure investment in Merivale area to enable higher densities in

the near future.

(d) Provide

opportunity to work with the private sector and government agencies to

facilitate more residential living opportunities, supported by appropriate

public spaces, community facilities and infrastructure

(e) Promote

greater diversity of housing supply that supports people remaining in their

community as they age.

(f) Support the growth

of university and hospital precincts

37. A full outline of the potential

benefits of the recommended option is contained within Attachment 4. The

total indicative monetised benefit accrued from the combined urban form and

multi-modal transport programme is in the realm of $1billion, with significant

urban form benefits coming from:

(a) GDP

benefits, and avoidance of potential GDP disbenefits

(b) Public

expenditure savings / infrastructure efficiencies

(c) Benefits

associated with agglomeration economics, including increased retail and

business trade and higher local income and employment

(d) Increased

property values and rental incomes.

38. Future

urban form will be supported by appropriate open space, community facilities

and consideration of heritage, culture and sense of place, developed in

collaboration with mana whenua and our communities.

Timing

of growth and supporting investment

39. Growth

and change will be incremental, evidence suggesting that residential change in

intensification areas generally occurs at a rate of about 10% every 10 years[1]. Recent commercial

development feasibility testing undertaken to support the Te Papa and Housing

Choice Plan Change projects acknowledges existing constraints (e.g. existing

land values, development costs) in the market that will need to be responded

to, to speed up development opportunities. However, we also know that there is

significant demand by Tauranga’s largest developers and other key

stakeholders (e.g., Accessible Properties and Kāinga Ora) to enable

development in these areas now. Input from development economic experts has

also emphasised the need for supporting investment (i.e. movement and community

infrastructure) as a significant factor in changing the value proposition for

investment in areas such as Te Papa.

40. Within

those areas where opportunity for higher densities is enabled through Plan

Change 26, the speed of development will also be impacted by supporting

investment in infrastructure, community amenities and catalyst projects

(including residential development), and factors such as the ebb and flow of

economic wellbeing and migration, impacted by national and global trends.

Similarly, the speed of supporting infrastructure delivery will also be tied to

key development milestones (as below).

41. In

this regard, the timing of the urban form and multi-modal transport programme

delivery remains subject to funding availability (at a local and national

level) and the uptake of residential development (by both the private and

public sectors). While the indicative timing proposed may change due to these

factors, the general order of investment should remain constant. Indicative timeframes

for those areas where development investment can be made to catalyse change are

recommended as follows:

(a) Immediate

focus on on-going city centre regeneration

(b) Gate

Pa / Pukehinahina: 5-15year focus on residential / community regeneration (reliant

on central government and key stakeholder collaboration)

(c) Merivale:

10+ year focus on residential / community regeneration (reliant on central

government and key stakeholder collaboration)

(d) Greerton:

20+ year focus on potential racecourse redevelopment (open space and housing;

subject to ongoing engagement with existing users, community, stakeholders and

mana whenua).

Transport

Options Considered and Preferred Way Forward

42. The

confirmation of a recommended Te Papa Peninsula urban form enables integration

opportunities between current and future land use, and necessary transport

investments and measures to accommodate growth forecast for Te Papa peninsula

and the wider Western Bay of Plenty.

43. To

support and integrate with the Te Papa peninsula and wider region’s urban

form, a suite of higher effectiveness multi-modal (walking, cycling,

micro-mobility and public transport) options were generated. These generally

require investment between $400m and $500m over 30 years but unlock significantly

higher (>1$billion) of urban system benefits long term.

44. Multi-modal

transport option development and testing by a Project Partner Technical Working

Group, has drawn in further domain and specialist inputs to inform the

assessments. Within the transport options developed, consideration was given

to:

(a) Quick

wins / standard interventions (0-3 years)

(b) Short

term interventions (0-10 years)

(c) Longer

term outcomes (10-30 years)

(d) Minimum,

ambitious and most ambitious outcomes

45. The

four options considered are outlined below, derived significantly from the

commonalities and approaches identified through the design sprint process. A

workshop held on 3 April 2020 identified Option 4, the ‘balanced’

active mode / public transport investment option (walking, cycling,

micro-mobility and public transport interventions), as performing best against

the Te Papa peninsula Investment Objectives, critical success factors and

related transport metrics commonly used by the Project Partners. A full

description of the ‘balanced’ active mode / public transport

investment option is provided further below.

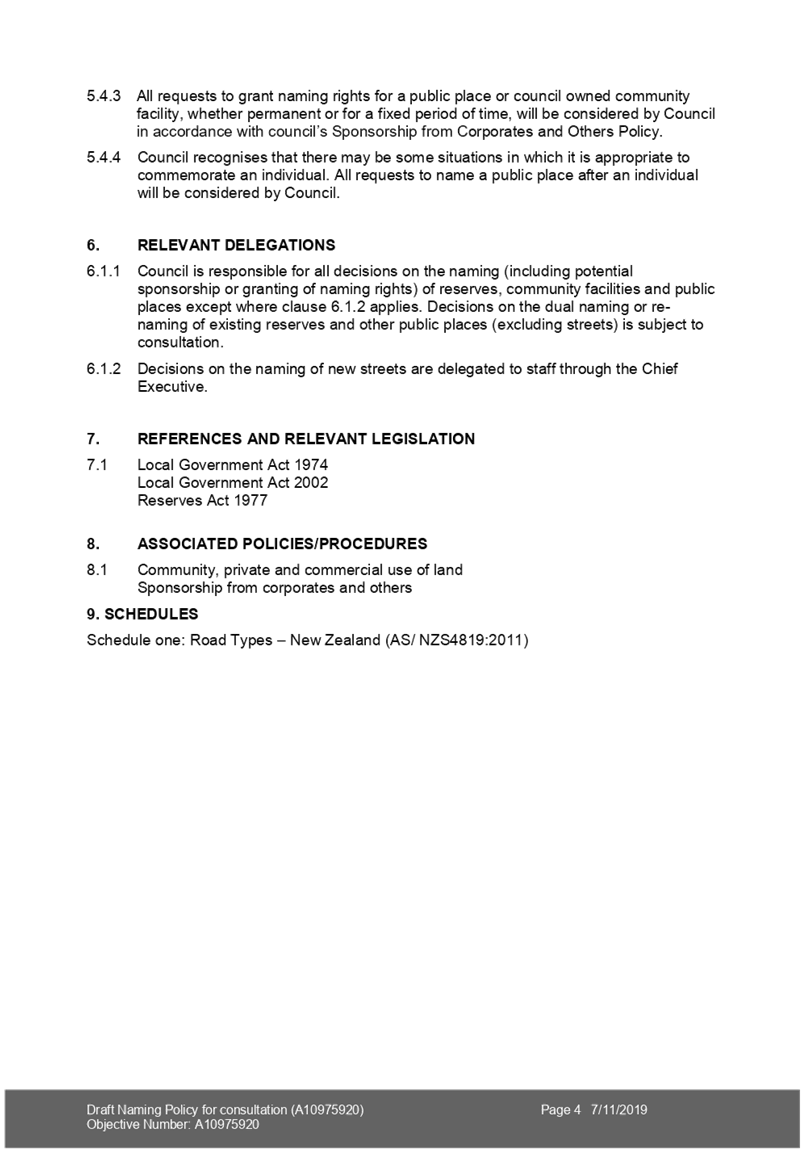

|

Option

|

Description

|

|

Option 1 – Low

investment scenario

|

Balanced investment in

public transport and active modes.

Provides a level of

safety for active modes given the likely increases in traffic and buses and

to provide the basic level of connectivity for cycle routes that is currently

lacking.

For public transport

(PT), the interventions seek to maintain a similar travel time to current,

using clearways and signal priority. Service frequency would be increased to

reflect the increased number of residents in Tauranga as a whole.

|

|

Option 2 – Active

and micro-mode focus

|

Provides safe and

connected facilities throughout the peninsula that people can access within a

short distance from their homes and destinations. Recognises that the

majority of trips within the peninsula are in range for many walking trips

and most cycle and micro mode trips.

With most origins and

destinations located a short distance from an arterial cycling /

micro-mobility arterial and high standard pedestrian connections, seeks to

maximise the uptake of active and micro-modes.

With the majority of

mode shift expected to be to active modes, the PT interventions reflect

option 1.

PT seeks to maintain a

similar travel time to current, using clearways and signal priority. Service

frequency would be increased to reflect the increased number of residents in

Tauranga as a whole with the view of moving people who can’t use active

modes or those travelling between the peninsula and other parts of the city.

|

|

Option 3 – PT

Focus

|

Provides a level of

safety for active modes given the likely increases in traffic and buses and

to provide the basic level of connectivity for cycle routes that is currently

lacking, as for option 1.

For PT, the

interventions seek to achieve a significant shift to PT for trips within the

Peninsula and for those originating elsewhere.

Fare policy,

infrastructure, priority measures and service design and frequency would be

focused on PT taking a high proportion of both shorter and longer trips.

|

|

Option 4 – Active

and PT Balance (preferred way forward)

|

This option recognises

that a balanced investment in both PT and active/micro modes could have the

best potential to move both internal and external trips away from single

occupancy vehicles and create the best mode shift scenario.

For active and micro-modes

it looks to provide safe and connected facilities throughout the peninsula

that people can access within a short to medium distance from their homes and

destinations. This recognises that the majority of trips within the peninsula

are in range for many walking trips and most cycle and micro mode trips.

The PT interventions

look to create frequent high quality PT facilities and services, that attract

users travelling within the peninsula as well as those originating elsewhere.

|

46. The

scale of growth required in Te Papa and the wider city means significant

further investment in movement networks is needed. Relative to the

recommended way forward, a basic investment package (i.e. the do minimum

option) sufficient to ‘just keep pace’ with Te Papa peninsula and

wider regional growth pressures and safety management issues will not

go far enough to deliver appropriate transport levels of service as the

population grows; nor will it avoid sufficiently avoid compounding land use

related liabilities and inefficiencies for travel time, housing affordability,

health outcomes, liveability or sustainability.

47. Transport

networks strongly influence and underpin urban systems. The relative emphasis

accorded to walking, cycling, micro-mobility, public transport, freight and

general vehicles strongly shapes the character, performance and long term

sustainability of urban areas. The urban form and multi-modal transport

programme recommended as part of the IBC will result in far more holistic

benefits for the city and community than other options considered, well aligned

with central government policy in this direction, as well as local strategic

direction for growth.

Detailed

summary of the recommended multi-modal transport programme

48. The

summary below is supported by the Te Papa multi-modal transport programme

10-year investment plans (walking, cycling, public transport and combined)

contained in Attachment 3.

49. Further

detail on the Transport Programme Indicative Costs is outlined in Attachment

5.

Walking

50. This

option seeks to create a balanced transport network of public, active and micro

modes. It was deemed that a much-improved active network is required to support

this balanced approach. With a high coverage of improvements, it was considered

to provide a medium level of service that focused around centres, corridors and

activity hubs.

51. The

approach seeks to upgrade approximately 75% of the footpaths sounding each of

the commercial, medium density and suburban residential zone areas to enable a higher

level of service (primarily footpath width and quality upgrades).

52. Within

each option the City Centre is considered vital to invest in streetscape

through footpath and urban realm improvements. On this assumption, the entire

area will see upgrades with 60% delivered to a very high quality and the

remaining 40% to a high quality.

53. Indicative

walking costs: $110m, including:

(a) Higher

quality city centre and commercial area paths to 3m wide

(b) Residential

area paths to 2m wide

(c) Basic

supporting streetscape upgrades in footpath corridor

(d) Total

of 110km of footpaths.

Cycling

54. Overall,

this programme aims to reduce the distance that people travel from their home

or destination to access high quality routes.

55. As

for option 2, this option identifies two continuous and safe north-south

connector for bikes and micro-mobility between the city centre and Greerton

connecting the land-use nodes along the peninsula and recognising that one

route does not serve all of the nodes well. Since it is likely that both would

be on busy routes, they are expected to be separated from traffic to provide

for safety and an adequate QOS. Optioneering on specific routes and whether the

cycleways would be bi-directional or single direction would be determined through

subsequent stages of work.

56. Even

though the key arterial cycle corridors would be separated from traffic they

are likely to be on busy routes, with trucks, buses and private cars. The

separation between north-south routes towards the southern end of the peninsula

is greater, with less scope to link people east to west. On this basis, one

further north-south route away from traffic is proposed to provide an

alternative link for recreational and less confident users and a logical link

for trips originating outside the peninsula.

57. In

terms of east west connectors, an arterial standard connector would be provided

approximately every 1- 1.5km, linking the north-south connectors to key land

uses. Again the specific routes and type of intervention would be identified

through the next stage. It is likely that routes would be predominantly

separated cycleways, recognising the volumes and potential speed of traffic. An

east-west connector between the suburbs of Gate Pa and Merivale is considered

as one of these key connectors. Due to the unsuitability of existing road

routes through industrial areas between the suburbs, this requires inclusion of

a connector from or around church road, which will likely require bridging of a

gully.

58. High

quality end of trip facilities would be rolled out at key centres, and also be

a requirement of developments as they occurred.

59. In

summary the option delivers:

· 2

North South commuter corridor

· 1

Coastal Recreational Shared Path

· 4

East West priority cycling corridors

· 2

Active transport bridges

· 23.061

KM of Primary cycling facilities

60. Indicative

cycling costs: $150m

Public

transport

61. This

programme will provide a lift in the level of service for public transport

within and through the peninsula to support active mode uptake by catering for

longer distance trips and allowing seamless connections. It will be supported

by priority measures, stops, and more frequent services.

62. Bus

lanes are provided on Cameron Road creating a strong corridor that can readily

be accessed by active modes. Clearways are provided on the secondary network to

improve network reliability and allow easy travel away from the peninsula.

Signalised intersections will be prioritised to reduce delay for public

transport where required.

63. Wayfinding

and real time information will be provisioned within the corridor to make

services more user friendly. A programme to deliver shelters at each bus stop

will be developed with high quality enclosed or semi enclosed shelters provided

at key stops on the primary and secondary networks to support active mode

interchange.

64. The

Tauranga city centre public transport hub will be completed as a priority

project allowing interchange between bus, ferry, and potentially inter-regional

rail services. This will be a high-quality facility that allows access to

e-mobility hire schemes to support the last-mile journey. Enclosed transport

hubs will be constructed at Greerton and Tauranga Hospital which will include

toilet facilities, bike lockers and sites for stalls or mobile food and coffee

vendors.

65. Service

frequency throughout the peninsula will steadily increase with services on

Cameron Road (in proximity to transport hubs) running up to every 2.5minutes by

2050. New routes will provide strong connections to the rest of the city. City

and Regional services will connect the peninsula to the rest of the Region and

beyond. This will give households viable public transport options, allowing a

significant increase in no-car and one-car households. Fares will be set at

affordable levels but not so low as to discourage active mode transport for

short trips (less than 5km).

66. In

summary the option delivers:

|

Priority on Bus network

|

|

|

Primary network:

|

All Day

|

|

Secondary network

|

Peak Periods

|

|

Tertiary network

|

minimal

|

|

Bus Fares

|

Encourage demand for

longer trips

|

|

Bus Service

Frequencies

|

In proximity to transport hubs

|

|

Primary network

|

Up to 2.5mins[2]

|

|

Secondary network

|

5mins

|

|

Tertiary

|

10mins

|

|

Non-priority

Infrastructure Projects

|

|

|

City Centre and

Hospital Transport Hubs

|

Year 5, higher quality,

contributes to civic function and amenity

|

|

Greerton and Hospital

bus facilities

|

Year 10

|

|

Turret Road 4-lane +

managed lanes*

|

To be confirmed through

Transport System Plan project

|

|

Improvements to public transport access and connections to

the Windermere education facility (Detailed Business Case required to

consider options further).

|

Year 30

|

|

Shelter Programme

|

High Quality

|

|

Real time

infrastructure + Wayfinding

|

Year 2

|

67. Indicative

public transport costs: $138m Capex; $52m Opex

General

interventions and soft side measures

68. Intersection

improvements:

· Focused

on improving actual and perceived level of safety for active users at key

locations

· Focus

on a high level of priority at intersections for public transport with high

quality facilities for active and micro-modes,

· Restrict

turning movements to left-in/left-out at uncontrolled intersections on key routes

and some secondary routes to improve conditions for vulnerable users and

improve reliability for buses

· Improve

local road intersections and intersections around schools and centres with a

focus on active and PT users

69. Neighbourhood

greenways and street improvements:

· Early

investment is upgrades of local routes to meet new street design guide

· Identifying

sense of place around key centres and PT hubs with urban upgrades x4

70. Speed

limits:

· Reduce

speed limits on local streets and around urban centres (recognising place

function)

· Ped

/ cycle crossing points

· Improve

frequency and standard of pedestrian and cycle crossing points on all key

routes and around key land-use and PT stops. Prioritise movements by active

modes and de-priorities private vehicles to give cycle and micro-modes a time

and directness advantage.

71. Soft

side measures include:

· Road

/ congestion pricing could be feasible given investment in alternatives if

changes in legislation were to occur. Consider charges to discourage through

traffic from using the peninsula use Takitimu Drive and the expressway for

through trips.

· Parking

policy and pricing – link to bus fares to ensure price competitiveness of

PT. Discourage parking on the city centre fringe through permit or pay schemes.

Reallocate some car parking space to cycle parking.

· Travel

plan requirements for new developments. Community, school and workplace travel

plans

· Amend

District Plan provisions to require parking and active mode end of trip

facilities in new developments.

Indicative

multi-modal programme timing

72. Proposed

timing seeks to support and catalyse growth in conjunction with key development

milestones and projected growth trajectories.

73. Over

the next 10 years, the Active and PT balanced option will focus

on the following transport related initiatives:

(a) Cameron

Road Multi-modal Corridor, stages 1 and 2

(b) 15th

Ave and Turret Road multi-modal and capacity upgrade

(c) Walking

and cycling improvements to increase mode share around centres and along PT

corridors, including:

(i) 3

east-west priority cycling and micro-mobility routes

(ii) Intersection

and safety improvements focussed on active users and public transport

(iii) Improved

pedestrian and cycle crossings on key routes

(iv) Improvements

to key local routes, including amenity, streetscape and footpaths around local

centres

(d) City

centre public transport hub

(e) Memorial

coastal multimodal pathway and other recreational routes

74. Over

the next 10 years and beyond, the Active and PT balanced option

will focus on the following transport related initiatives:

(a) City

Centre street upgrades and public realm: streetscape and waterfront development

(short to medium term)

(b) Walking

and cycling improvements to increase mode share throughout the wider peninsula

(c) Greerton

and hospital public transport hubs

75. For

the 30 year+ vision for Cameron Road, the Active and PT balanced option

provides a focus on multi-modal transport provision, including dedicated bus

lanes (providing for bus frequencies up to up to every 2.5minutes in core

locations, connecting with the wider network) and with potential for future Bus

Rapid Transit, trackless trams or similar to be provided through appropriate

route protection. This level of intervention will subject to a further detailed

business case.

76. Complex

interventions where there is a high level of risk and/or uncertainty will be

identified as requiring further work to be undertaken, such as a Detailed

Business Case phase. Fast tracking of standard interventions that are

relatively low risk will also be enabled by the IBC. These interventions will

be derived from existing evidence base (e.g. other business cases) where the

evidence and justification for the intervention and standard interventions has

already been established.

77. A full outline of the potential

benefits of the recommended option is contained within Attachment 4. As

described above, the total indicative monetised benefit accrued from the

combined urban form and multi-modal transport programme is in the realm of

$1billion, with significant multi-modal transport benefits coming from:

(a) Health

benefits

(b) Modal

shift (walking, cycling and public transport) related benefits

(c) Travel

time cost savings

(d) Trip

reliability

(e) Vehicle

operating savings

(f) Crash

savings

(g) Environmental

benefits (reduced relative CO2 emissions)

Financial Considerations

78. As

noted above and taking into account wider investment that will be required in

infrastructure and community amenities, the indicative benefit cost ratio (BCR)

associated with the recommended urban form and multi-modal transport programme

is estimated to be between 1.5:1 and 2:1. A description of project benefits,

including monetisation is included in Attachment 4.

Legal Implications / Risks

79. Risks

of not acting includes inconsistency with central government direction,

including emerging direction on growth as identified within the draft NPS-UD.

80. The

risks of not acting also includes exacerbating the existing Tauranga housing

shortage and associated economic and social costs.

Significance

81. Having

regard to Council’s Significance and Engagement Policy, significance of

this project is considered ‘high’. It affects a wide range of

people; has moderate to high public interest; and will have a large consequence

for the city in terms of growth over time. As outlined within this report,

community, stakeholder and mana whenua engagement is ongoing, including

opportunity to provide feedback in relation to aspects of the urban form and

transport recommendations developed as part of the IBC. Further opportunities

for engagement will also be provided through the Long-Term Plan process and project

delivery stages.

Next Steps

82. Subject

to Council’s approval of the IBC being submitted to for NZTA approval,

the next steps in this process are:

(a) The

IBC is submitted to NZTA’s Operational Policy, Planning and Performance

Delegations Committee on 14 May 2020

(b) Subject

to the Operational Policy, Planning and Performance Delegations Committee

approval, the IBC is submitted to NZTA’s Investment and Operations

Committee (date to be confirmed)

(c) Subject

to the Investment and Operations Committee approval, the IBC is submitted to

NZTA’s Board on 18 June 2020, alongside the UFTI programme Business Case.

(d) Subject

all approvals, planning for standard interventions and

detailed business cases commences from August onwards.

Attachments

1. Te

Papa Indictive Business Case Summary Document - A11413470 ⇩

2. Te Papa Indictive

Business Case Urban Form Preferred Way Forward – Centre Plus Plan -

A11407317 ⇩

3. Te Papa Indictive

Business Case Multi-Modal Transport Programme 10 Year Investment Plans -

A11407318 ⇩

4. Te Papa Indictive

Business Case Benefits - A11407319 ⇩

5. Te Papa Indicative

Business Case – Indicative Project Costs - A11411386 ⇩

|

Ordinary Council

Meeting Agenda

|

5 May 2020

|

|

Ordinary Council Meeting Agenda

|

5 May 2020

|

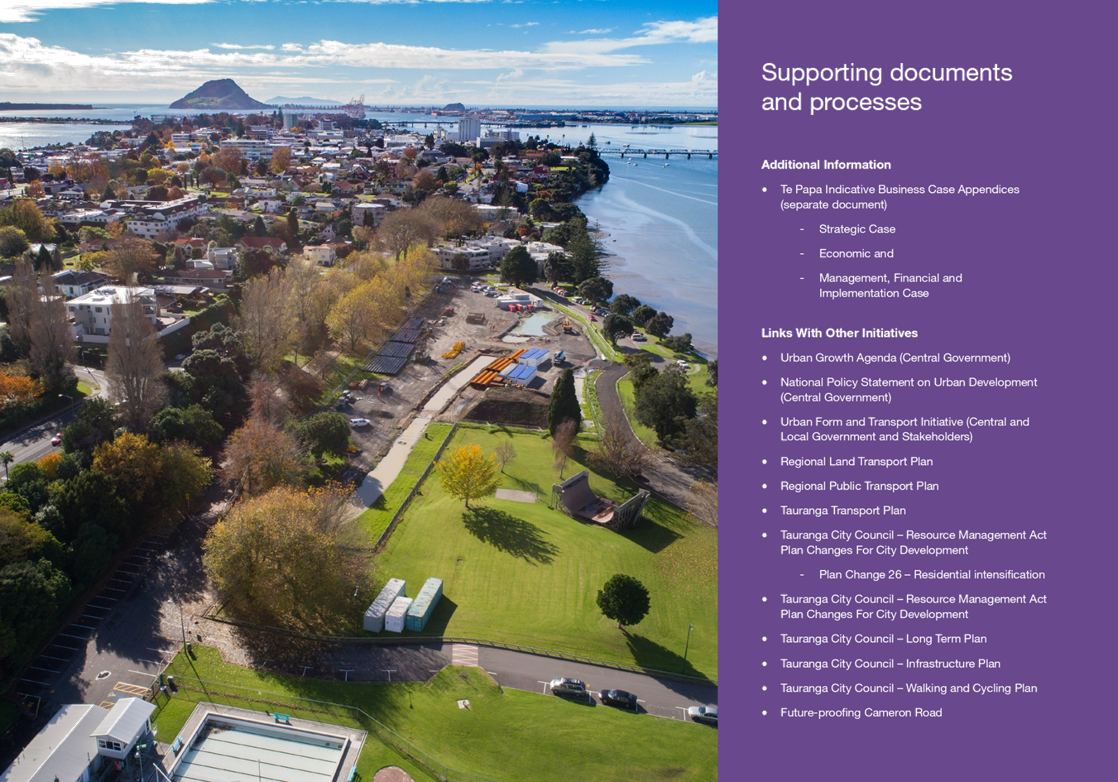

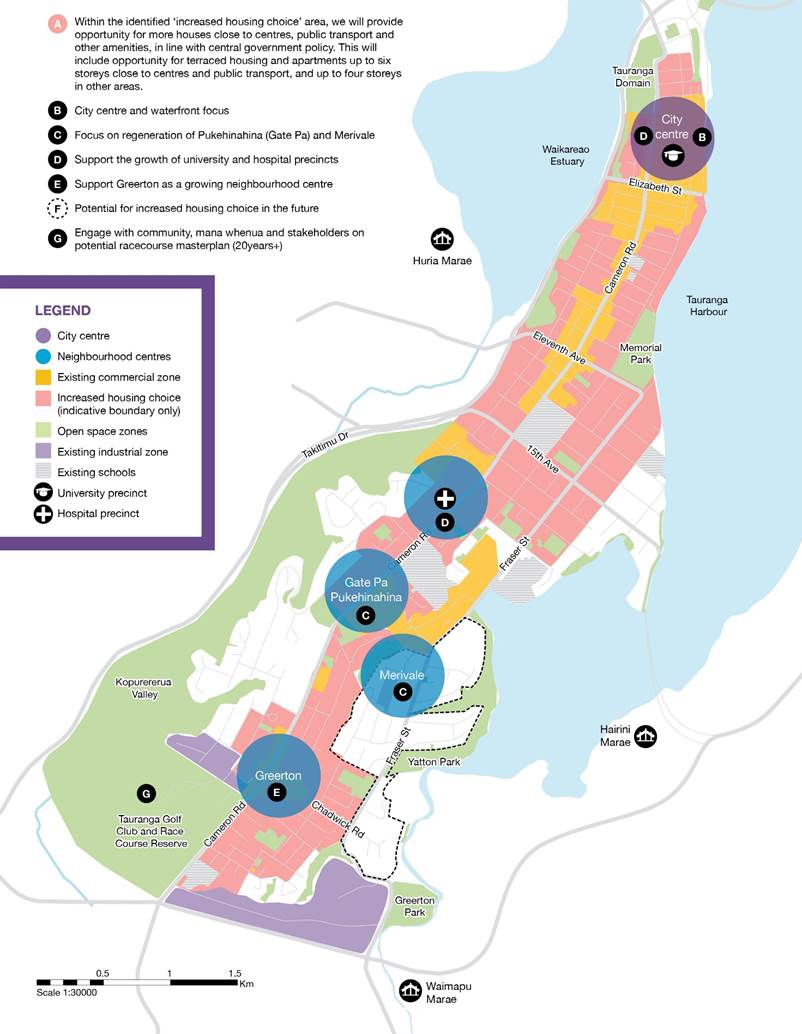

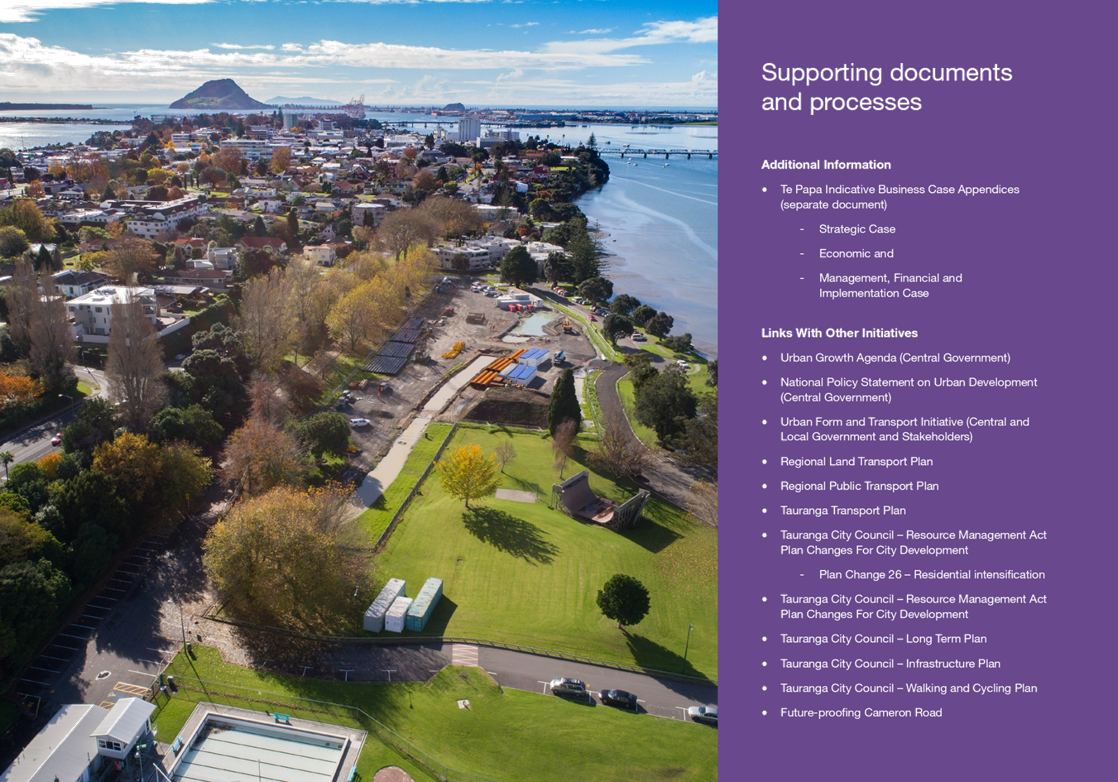

Te Papa Indictive Business Case

Urban Form Preferred Way Forward – Centre plus Plan

Source: Te Papa

Spatial Plan Outcomes and Ideas Discussion Document

|

Ordinary Council Meeting Agenda

|

5 May 2020

|

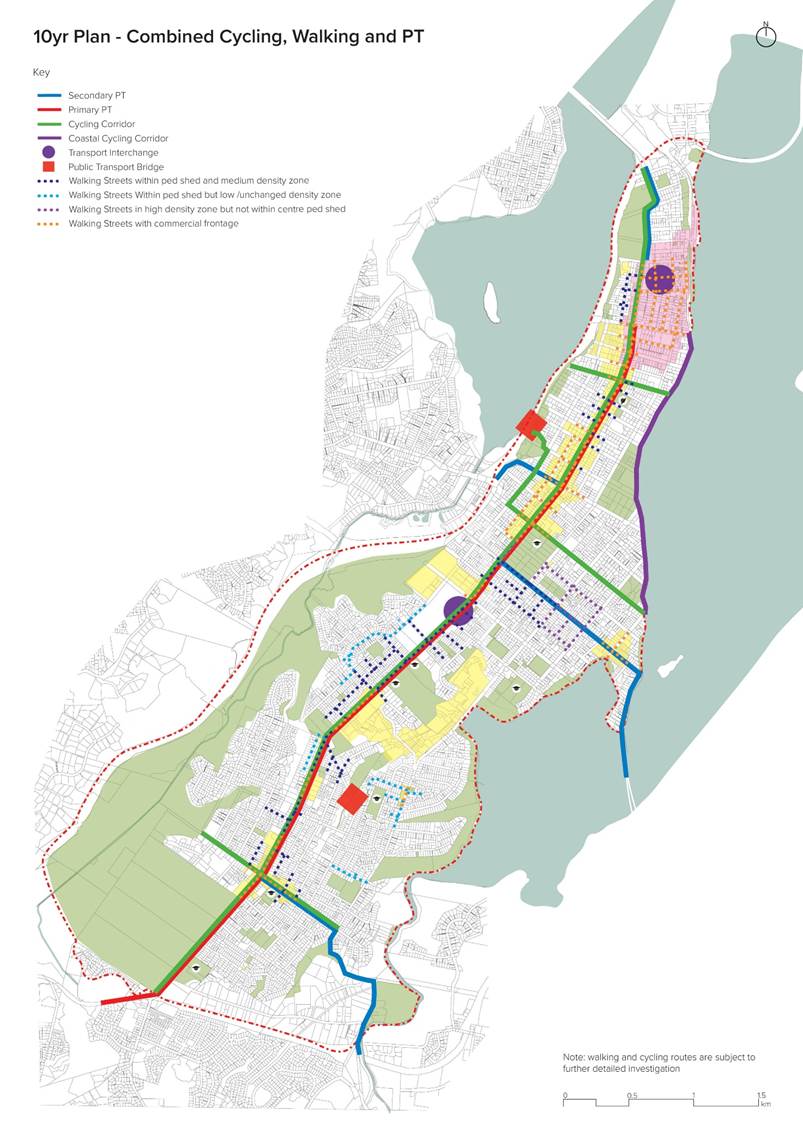

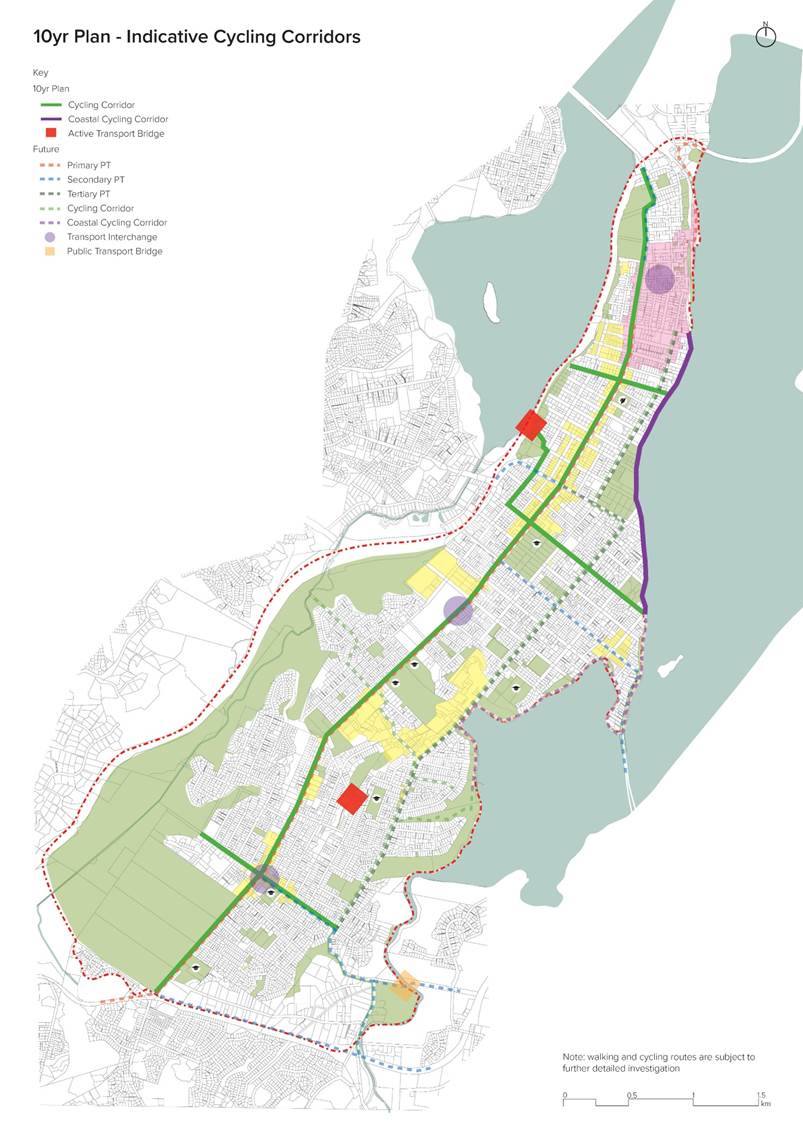

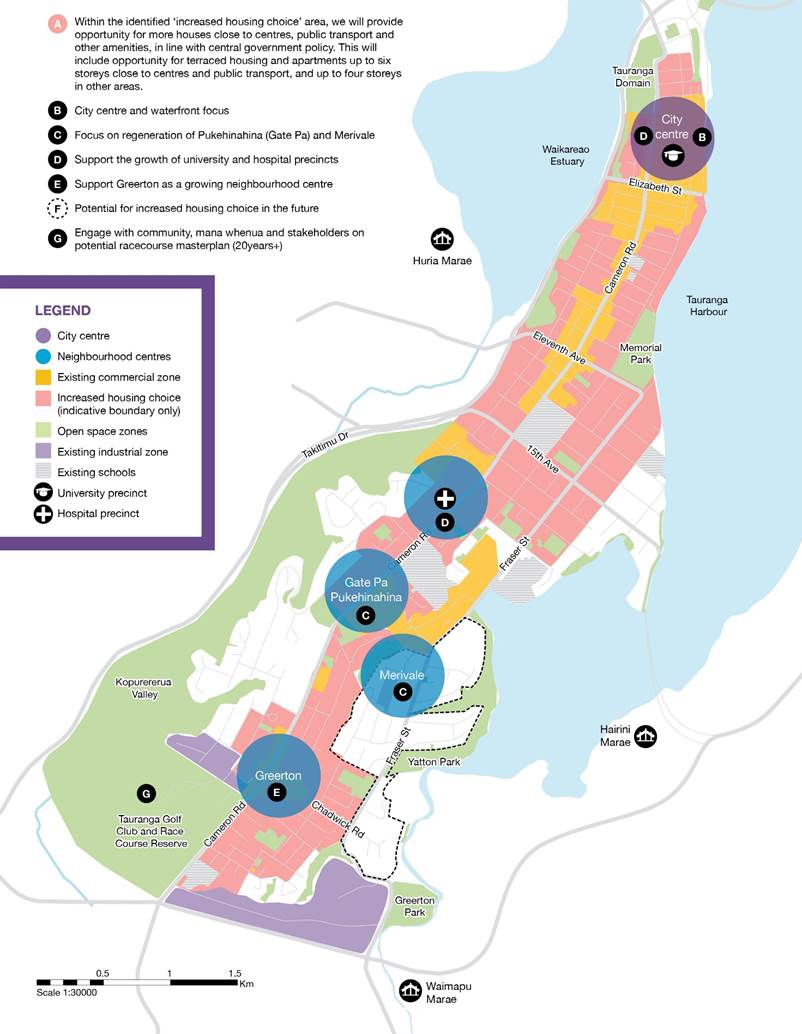

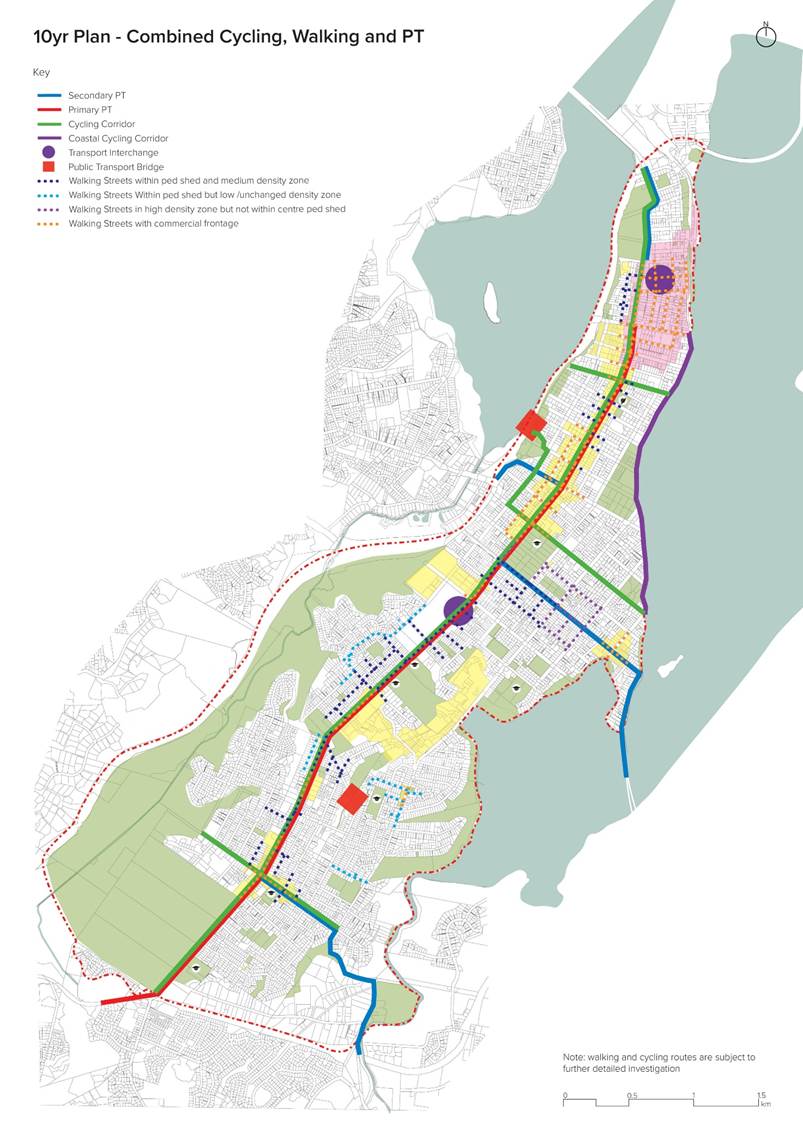

Te Papa Indictive Business Case

Multi-Modal Transport Programme 10 Year Investment Plans

Te Papa Indictive Business Case

Benefits

1. This

attachment provides and overview of the potential benefits associated with the

Te Papa IBC preferred way forward as it relates to urban form and transport

interventions.

2. The

IBC assessment recognises Te Papa peninsula as a central element within the

wider urban system of Tauranga City and the Western Bay of Plenty, with ability

to release over $1billion in present value benefits to the community. In this

regard, and taking into account wider investment that will be required in

infrastructure and community amenities, the indicative benefit cost ratio (BCR)

associated with the recommended urban form and multi-modal transport programme

is estimated to be between 1.5:1 and 2:1.

3. The

recommended urban form and transport interventions will contribute to the

growth of the area and wider city in the coming 30 years. Growth projections

that form part of the Business Case include potential for up to 29,300

additional residents, 19,400 additional homes, and a 15,000 (60%) increase in

employees throughout the peninsula.

4. At

a high level, when compared to a ‘do minimum’ approach, the

recommended urban form and transport interventions have potential for

significant increases in the overall investment value with Te Papa (and

associated development benefits to get there), GDP contribution, and increase

in salaries and wages:

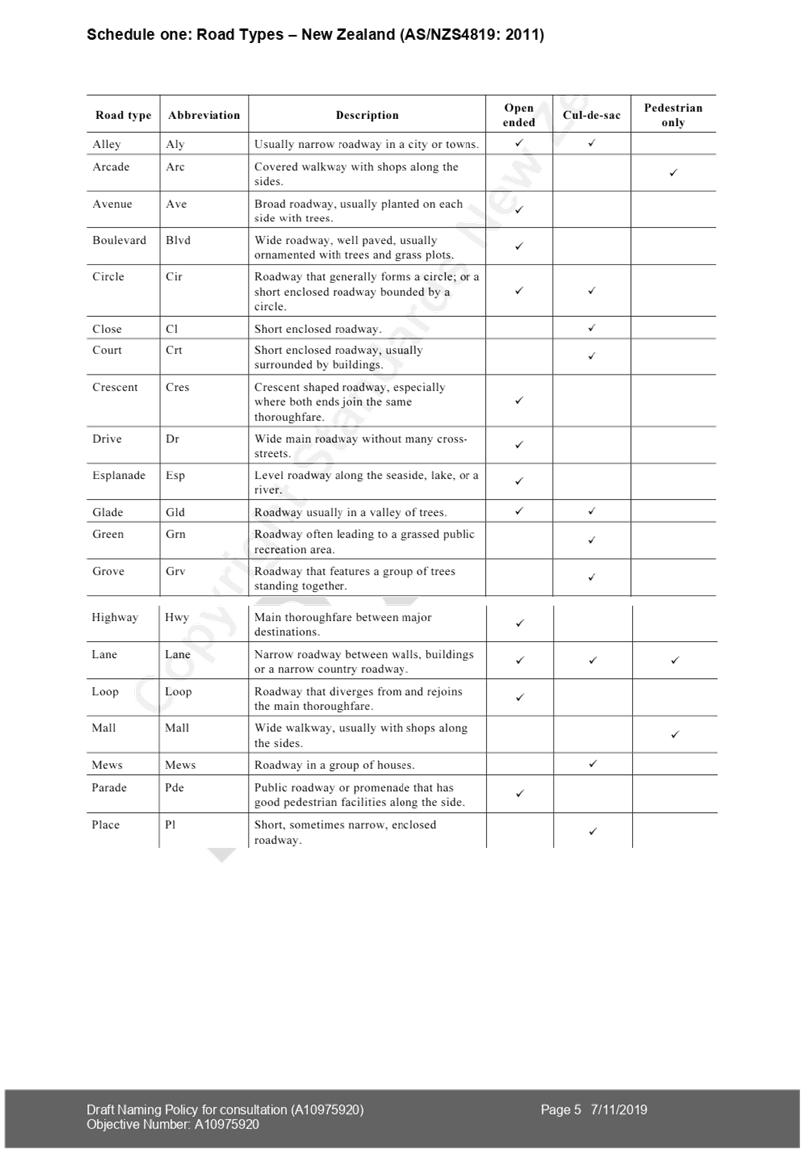

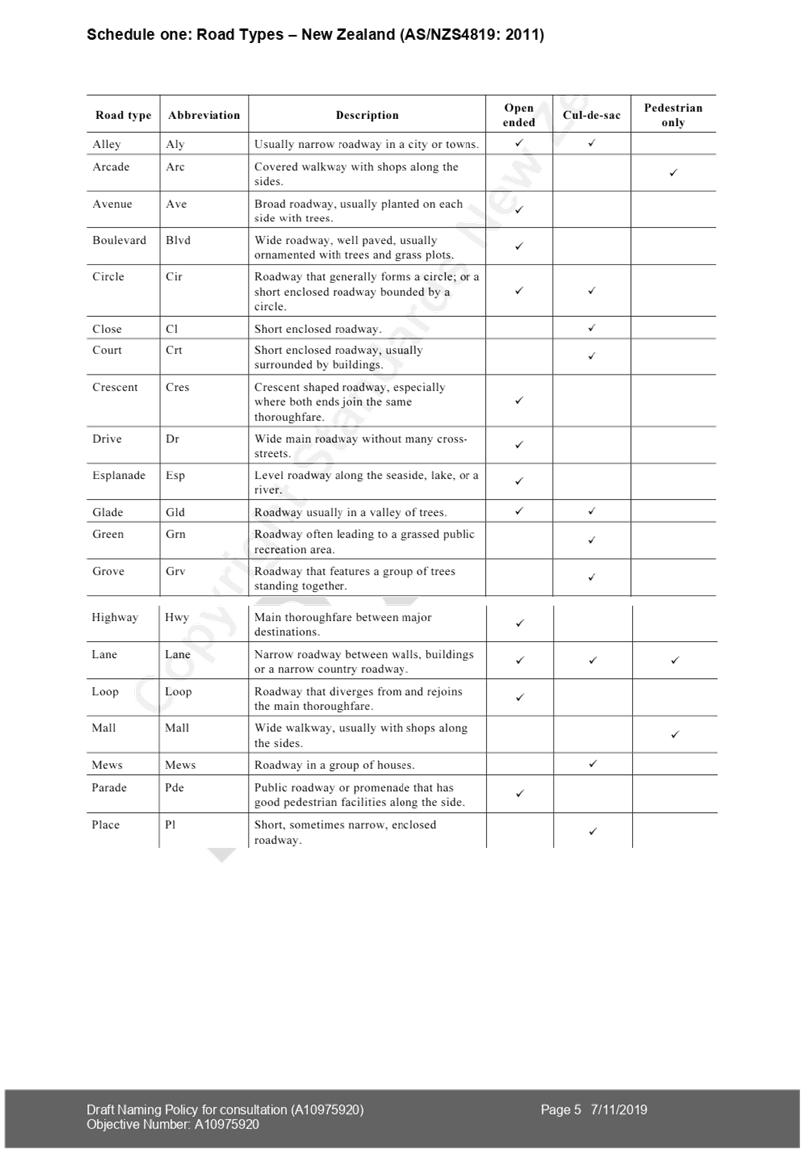

|

Do

minimum growth scenario

|

Preferred

Way Forward

|

|

Te

Papa Total Dwellings

|

+2,400

|

+19,400

|

|

Resident

Population

|

+3,600

|

+29,300

|

|

Employees

|

+9,500

|

+14,900

|

|

Te

Papa Estimated Dwelling Value

|

+$1.5b

|

+$11.6b

|

|

GDP

contribution

|

+$90m

p.a.

|

+$730m

p.a.

|

|

Salaries

and wages

|

+$400m

p.a.

|

+$630m

p.a.

|

5. The

urban form and multi-modal transport programme recommended will result in a

range of benefits for the city and Te Papa, including:

(a) Better

and more equitable access to social and economic opportunities

(b) Housing

that meets our needs

(c) More

opportunities for meaningful employment and economic growth in Te Papa

(d) Neighbourhoods

that are more liveable and have a stronger sense of culture and identity

(e) Improvements

in environmental quality.

These benefits are described in

more detail hereafter.

Better

and more equitable access to social and economic opportunities

6. Benefits

associated with ‘better and more equitable access to social and economic

opportunities’ include:

(a) Enabling greater choice,

quality, convenience and perceptions of choice has potential to increase active

modes and micro-mobility usage by more than double within 10 years and over

three times in 30 years.

(b) Public

transport usage by Te Papa residents can increase by over three times in 10

years and 10 times over 30 years. The network provided has an even more

significant role to play in the wider region for people to access jobs,

education, recreation, community and health services.

(c) Higher

levels of service relative to lower investment options.

(d) More

inclusive access for all users.

(e) Economic

benefits associated with more efficient transport infrastructure, including

trip reliability, trip time cost savings, operating savings and crash savings.

(f) Improved

perceived and actual safety for all transport users and the wider public.

(g) Improved

community health through increases of persons using active travel modes

(walking, cycling, micro-mobility and accessing public transport), with up $77m

of avoided health costs with a projected doubling of active mode travel choice

(based on $4,500 per person per lifetime health cost savings for intensified

urban areas)

(h) Transport

system multi-modal benefits (walking, cycling, micro-mobility and public

transport) assessed at greater than $350m over 30 years.

Housing

that meets our needs

7. Benefits

associated with ‘housing that meets our needs’ include:

(a) Potential

for up to 19,400 additional homes, providing increased housing availability and

choice including both mix of tenures and varied price points.

(b) Potential

to assist in improving relative housing affordability within wider region.

(c) Property

value increases averaging more than $150,000 per property, while simultaneously

seeing increases in wider housing stock availability that benefits lower income

households.

(d) Avoided GDP loss of $450m over

10 years due to housing issues

(e) Efficient

use of infrastructure through intensification, and associated savings to

Council and the community. Based on comparable cities (which have shown much

higher figures), these efficiencies potentially run at more than $25m for each

1000 households accommodated when compared with greenfields development. For

the projected 15,000+ additional households in Te Papa peninsula this equates

to a public sector investment efficiency gain of circa $375m.

(f) Integrated

urban form decision-making creating synergistic benefits: strongly aligned and

co-ordinated investment between government entities produces timing and

procurement efficiencies, and gives greater investment direction and certainty to

the private sector.

More

opportunities for meaningful employment and economic growth in Te Papa

8. Benefits

associated with ‘more opportunities for meaningful employment and

economic growth in Te Papa’ include:

(a) Employment

/ creation of jobs including, in in the short term, through construction,

including:

(i) Delivery

of new and upgraded housing, commercial, social and recreational infrastructure

as well as the transport and 3-waters infrastructure

(ii) Delivery

of new employment growth, catering to the local and regional markets.

(b) The

Te Papa peninsula will accommodate a significant proportion of the projected

employment growth for Tauranga in strong, well-performing local centres and the

city centre. These business locations are efficiently accessed across the

transport system, which will result in increased and sustained economic

productivity and prosperity.

(c) Significant

increases in agglomeration economies; strengthening of Te Papa business centre

occupancy, vibrancy and employment opportunities, with a focus on Tauranga city

centre’s $1.7b per annum GDP.

(d) Increased

attractiveness of Te Papa peninsula as an employment location through enhanced

urban form and multi-modal transport choices can accelerate job creation and

lift average wages through agglomeration effects.

(e) Wage

earning growth driven by density equating to over $12m to $23m+per 5 years for

each 10% density increase Productivity gains of $140m in 10 years, $650m 30

years.

(f) Significant

contribution to GDP associated with development and increases in local

employment, wages and salaries.

(g) Increasing

urban population by 10% raises wages by 0.2 to 0.5%.

(h) Doubling

urban density, on average, increases productivity by 2% to 6%.

(i) 10%

increase in ‘walking Effective Job Density’ (EJD) associated with a

>5% increase in productivity.

Neighbourhoods that are more liveable and have a

stronger sense of culture and identity

9. Benefits

associated with ‘neighbourhoods that are more liveable and have a

stronger sense of culture and identity’ include:

(a) Improved

environment and health outcomes, and positive impacts on sense of place and

identity.

(b) Strengthened

ratings of Te Papa peninsula liveability through better integrated urban form

and multi-modal transport networks:

(i) Community

ratings of liveability, identity and acknowledgement and respect for culture

(Tauranga City Council – Annual Surveys)

(ii) Māori

and Pacific cultural needs are recognised: Partnership involvement to inform

and shape urban decision-making to support identity, and well-being factors.

(c) Strengthened

cultural design considerations into investment into the Te Papa peninsula and

wider urban fabric.

(d) Enabling

people to live, work, play and learn within their community through enabling self-containment

will provide for a sustainable community.

(e) Multi-modal

transport opportunities will enable people to access social opportunities more

easily.

Improvements

in environmental quality

10. Benefits

associated with ‘improvements in environmental quality’ include:

(a) Reduced

emissions to the environment through greater uptake of sustainable travel

modes; potential for emissions to lessen by >35% relative to status quo

urban form development; CO2 emission savings at circa $3m.

(b) More

sustainable urban form design responses.

(c) Future

developments in the Peninsula will assist in greening the peninsula, reducing

carbon emissions, using resources efficiently, protecting our cultural heritage

and contributing to eco-system health and bio-diversity.

(d) Improving

multi-modal transport options and enabling intensified development close to

existing social and economic infrastructure will reduce emissions from

transport compared to additional greenfield dispersed development beyond that

already planned.

Summary

of monetised benefits

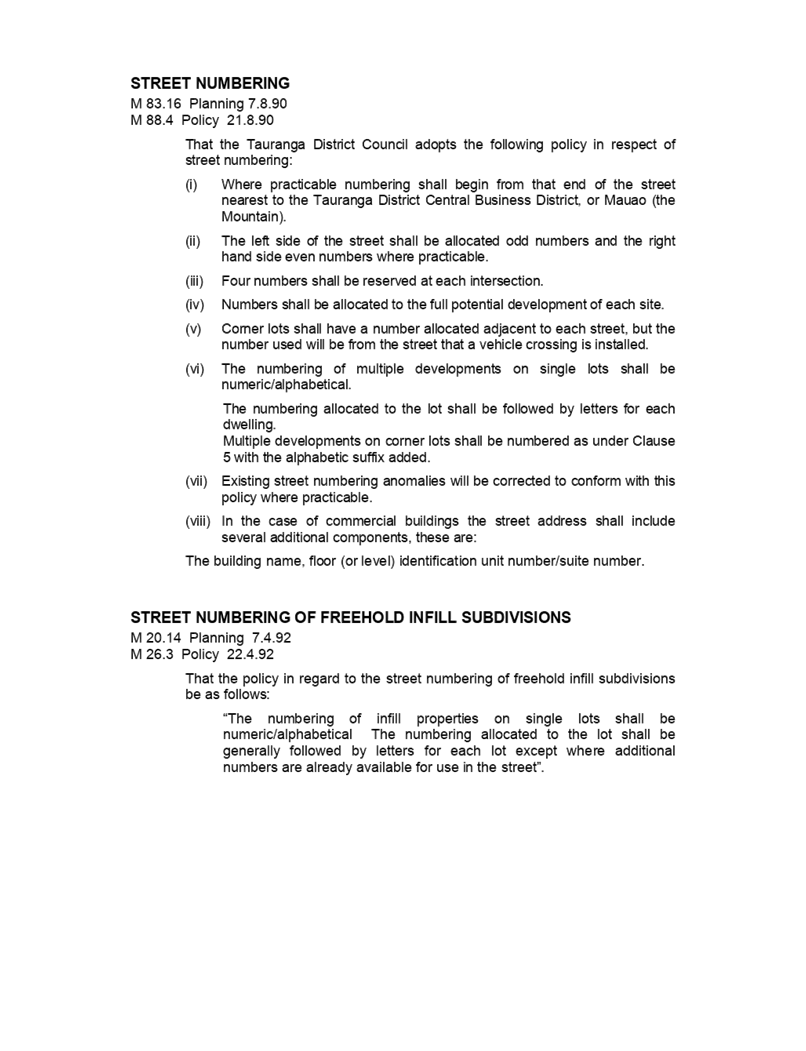

11. The

monetised benefits arising from the urban form and transport interventions are

summarised as follows:

|

Economic factor

|

Value

|

Coverage / notes

|

|

Wider economic

benefits

|

$2.2billion over 30

years (includes significant avoided public expenditure avoided costs)

The above translates

to a NPV of approximately $1billion.

|

· Public

expenditure benefit of Te Papa peninsula efficiency in accommodating urban

growth

· Wage

uplift for each 10% density increase.

· Productivity

gains of 2% to 6% for each doubling of density

· Avoided

health costs for population transferring to active modes within Te Papa

($4500 per resident)

· GDP

strengthening on $1.7b p.a. Tauranga city centre with intensification

· Capital

value increases for HHd and business associated with ‘20 minute’

neighbourhood characteristics.

· Induced

/ improved access to housing for lower income houses with flow on benefits

to social outcomes

· Avoided

GDP losses due to housing constraints / mismatches

|

|

Active Modes

|

$77million over 30

years

|

· 160%

active modes and micro-mobility usage within 10 years

· 300%

(2500 additional Te Papa peninsula residents) in 30 years

· Supports

wider regional network functioning and usage

|

|

Public transport

benefits

|

Modelling confirmation

work for May 2020

|

· 300%

increase in 10 years

· More

than 10 times over 30 years

|

|

CO2

|

$3million

|

· To

be confirmed via modelling

|

|

Travel time costs

|

Modelling confirmation

work for May 2020

|

· Achievement

of mode shift within Te Papa peninsula results in maintained demand on road

network for car users. Network will face growth pressure from wider

Western Bay of Plenty development dynamics.

|

|

Trip reliability

|

Modelling confirmation

work for May 2020

|

· Achievement

of modal shift within Te Papa enables transport network to better service

wider Western Bay of Plenty access and travel needs

|

|

Vehicle operating

savings

|

$25

|

· Cumulative

modal shift benefits over 30 years of residents moving to walking and cycling

|

|

Crash savings

|

Modelling confirmation

work for May 2020

|

· To

be confirmed via modelling

|

|

NPV total

|

>$1 b

|

· Indicative

BCR 1.5 to 2

|

|

Ordinary Council Meeting Agenda

|

5 May 2020

|

Te Papa Indicative

Business Case – Indicative Project Costs

Last updated:

23 April 2020

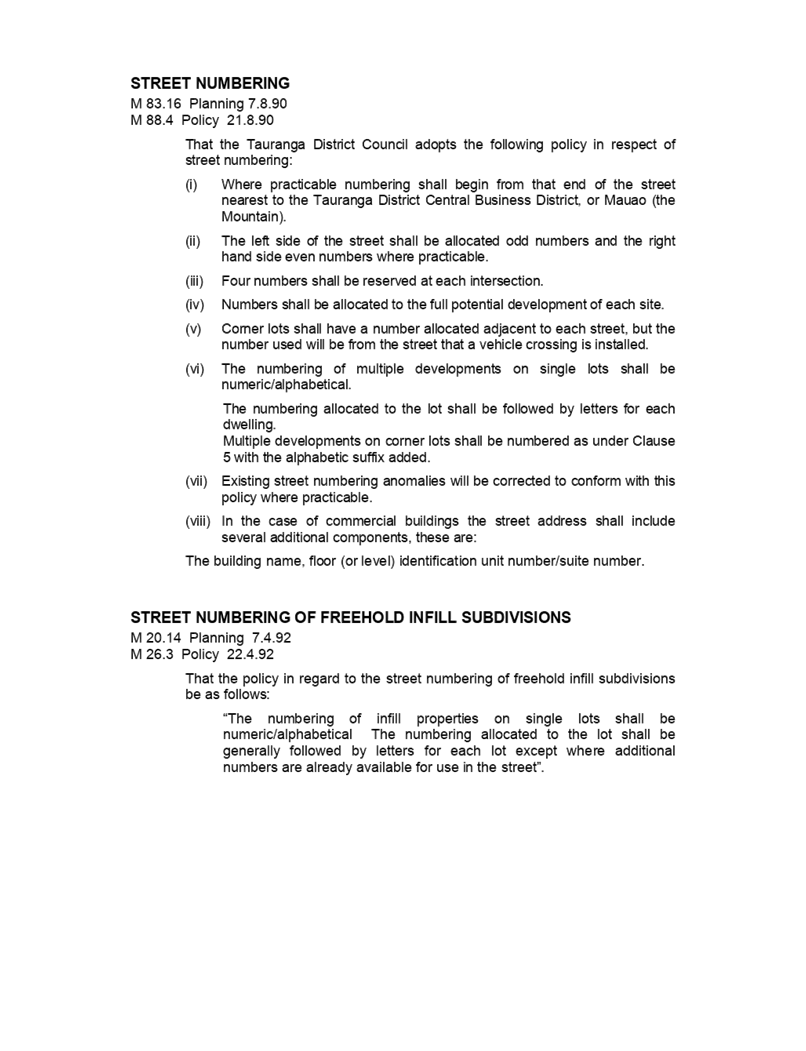

Indicative Project Capital Costs

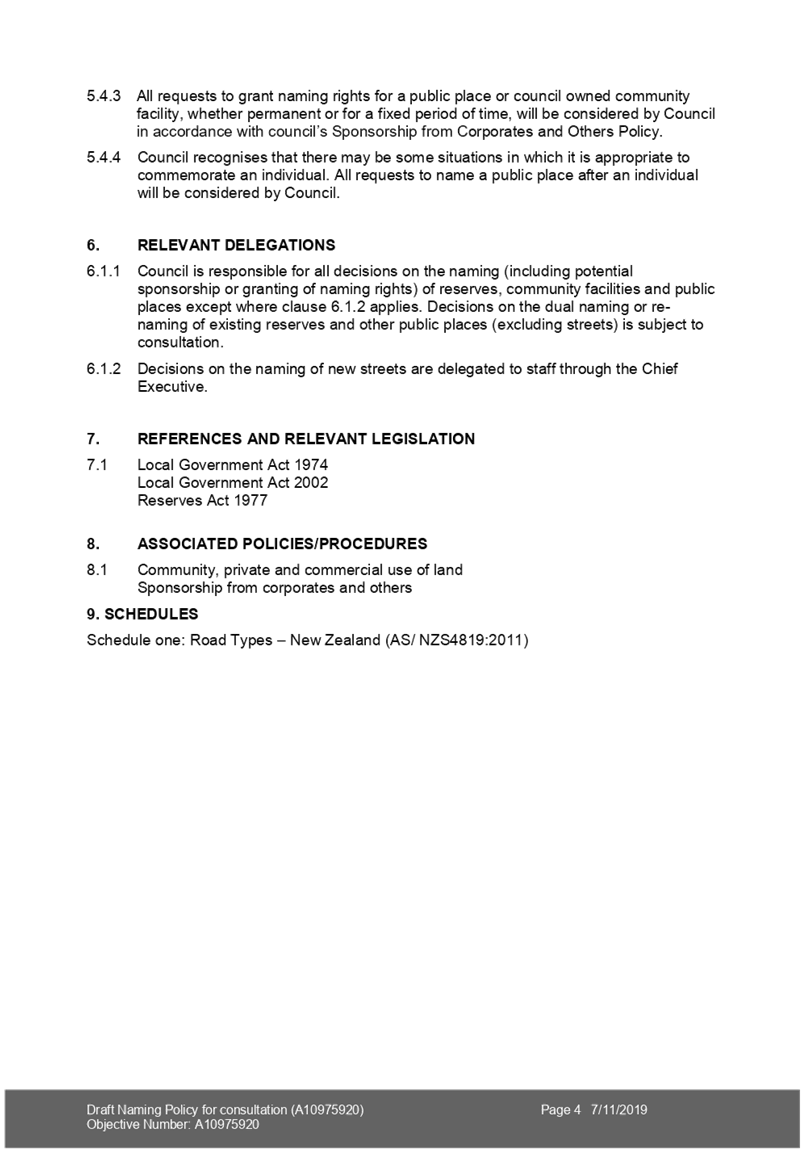

|

Project

|

Total Costs

|

2021-2030 Costs

|

2031-2050 Costs

|

Notes

|

|

Transport

|

($m)

|

($m)

|

($m)

|

|

|

Cameron Road Multi Modal

‘Stage 1’

|

40.00

|

40.00

|

0.00

|

current estimated design and

construct cost; includes walking, cycling and PT

|

|

Cameron Road Multi Modal

‘Stage 2’

|

60.00

|

60.00

|

0.00

|

current estimated design and

construct cost; includes walking, cycling and PT

|

|

Walking

|

92.00

|

19.00

|

73.00

|

excludes double up with

Cameron Road (value $18m)

|

|

Cycling

|

126.00

|

62.00

|

64.00

|

excludes double up with

Cameron Road (value $23.5m)

|

|

City Centre Transport Hub,

Hospital, Greerton

|

50.00

|

40.00

|

10.00

|

$30m city centre; $10m others

|

|

Turrent Rd / 15th Ave

|

NA

|

-

|

-

|

Regional / TSP project

($100m)

|

|

Other PT related Capex,

includes secondary and tertiary network improvements, signals, shelters, etc.

|

32.00

|

16.00

|

16.00

|

Regional Council estimate.

Assumption: apportioned 50/50

|

|

Total Transport

Costs

|

400.00

|

237.00

|

163.00

|

|

|

Community Amenities

|

|

|

|

|

|

Memorial Park Aquatic

Centre

|

90.00

|

90.00

|

0.00

|

Current upper estimate

|

|

Central Library

|

35.00

|

35.00

|

0.00

|

Current estimate

|

|

Museum

|

NA

|

|

|

Not included; potential for

more cost effective options; ($56m)

|

|

City Centre / waterfront /

streetscape improvements

|

36.00

|

36.00

|

TBC

|

Based on current project estimates;

further programme confirmation and costing required for post 2030 timeframes

|

|

Community amenities and opens

space – general

|

97.00

|

48.50

|

48.50

|

Includes BVL capital works,

existing community facility upgrades, community centres, LoS upgrades for

open space, greenway improvements, and other improvements to support

increased population. Supporting: Apportioned 50/50

|

|

Total Community Amenities

Costs

|

258.00

|

209.50

|

48.50

|

|

|

Three Waters

Infrastructure

|

|

|

|

|

|

Water supply

|

10.00

|

10.00

|

TBC

|

Based on 3-waters

investigations and current LTP funding; further studies due late 2020; notes

significant short-medium term capacity

|

|

Wastewater

|

10.00

|

10.00

|

TBC

|

Based on 3-waters

investigations and current LTP funding; further studies due late 2020; notes

significant short-medium term capacity

|

|

Stormwater alleviation

|

150.00

|

75.00

|

75.00

|

estimate to provide

stormwater mitigation and address overland flow paths

|

|

Estimated 3-waters

Costs

|

170.00

|

95.00

|

75.00

|

|

|

Marginal 3-waters cost to

support development (30%)

|

51.00

|

28.50

|

22.50

|

Estimate of costs

attributed to Te Papa development requirements (as opposed to renewals and

wider capacity needs)

|

|

Total Costs

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total Costs

|

709.00

|

475.50

|

234.00

|

|

Indicative Project Operational Costs

|

Project

|

Total Costs

|

2021-2030 Costs

|

2031-2050 Costs

|

Notes

|

|

Transport

|

($m)

|

($m)

|

($m)

|

|

|

PT Opex costs

|

52.00

|

21.00

|

31.00

|

Regional Council estimate.

Assumption: Apportioned 40/60

|

10.2 Annual

Plan Review Process

File

Number: A11427798

Author: Jeremy

Boase, Manager: Strategy and Corporate Planning

Authoriser: Christine

Jones, General Manager: Strategy & Growth

Purpose of the Report

1. To

provide Council with a summary of the proposed approach and framework for a

revised approach to the 2020/21 Annual Plan taking into account the

significantly altered financial scenarios that COVID-19 restrictions have

resulted in.

|

Recommendations

That the Council:

(a) Endorses

the approach proposed through this report to review the draft 2020/21 Annual

Plan.

(b) Requests

that staff report back on options for a revised draft 2020/21 Annual Plan

once the review is substantively progressed.

|

Executive Summary

2. This

report provides an overview of the approach and framework for delivering the

2020/21 Annual Plan in a manner which reflects the impacts of COVID-19 on

Council.

3. The paper outlines workstreams

which are underway to consider:

· Reducing

the level of capital expenditure

· Reducing

operating expenditure

· Arrangements

for external funding or off-balance sheet financing

4. While not covered in detail in this paper, there are two further

workstreams underway which will also inform the development of the final

2020/21 Annual Plan. These are:

· Non-funding

operational expenditure

· Amending

the acceptable planning target for the debt-to-revenue ratio.

5. These

workstreams will help inform the development of a prudent, sustainable and affordable

2020/21 Annual Plan and will also help inform ongoing engagement with partners

regarding the impact of COVID-19 on Council’s finances and service

capacity.

6. Information is also provided about different scenarios and issues

for the timing of, and potential further consultation on, the final Annual

Plan.

Background

7. A report was presented to

the 21 April 2020 Council meeting outlining the potential impacts of a

combination of COVID-19 and Council’s underlying financial position on

the 2020/21 Annual Plan. Please refer to that report for background that

is equally relevant to this report.

8. On

receiving that report, Council resolved to seek further direction from the

Executive on a response to those potential impacts.

9. This

report provides Council with an overview of the work the Executive are

progressing to deliver on the decision of Council.

Creating a new budget in an

uncertain world

10. The

report to the 21 April Council meeting indicated that next year’s revenue

could be anywhere from $40 million to $77 million less than currently budgeted

in the draft Annual Plan. These figures were based on initial high-level

modelling under two different scenarios, one with significant restrictions on

movement, gatherings and social distancing for the whole of 2020/21, and one

for six months of such restrictions followed by six months of lesser impact.

11. Such

impacts on projected revenues have two distinct (but related)

consequences. Firstly, because of Council’s debt-to-revenue ratio

constraints, reduced revenue means reduced debt capacity. This means that

Council has less opportunity to use debt-financing to either pay for capital

expenditure projects or, as some councils have publicly stated they intend to

do, to fund operating expenses. Secondly, in order to create a

‘balanced budget[3]’

reduced operating revenue means Council needs to reduce its operating expenses

to match.

The

‘levers’ available

12. In

looking to significantly revise the 2020/21 budget to meet the necessary

parameters, there are a number of options available. These options are

not mutually exclusive; it is likely that any optimal budget-setting process

will include elements of many of the options.

13. The

options available which the Executive are proceeding to focus on include, but

may not be limited to:

· Reducing the

level of capital expenditure

To reduce cash outflow and

therefore debt levels, and also to reduce consequent operating expenditure

(‘pure’ operating expenditure as well as debt servicing and

depreciation costs).

· Reducing

operating expenditure

To reduce cash outflow and, with

reduced revenue, any need to fund operations from debt.

· Arrangement

of external funding or off-balance sheet financing

This could be an injection of

funding for capital projects or for operating expenses or both and could ease

the debt burden or the balanced budget burden or both.

· Non-Funding

operational expenditure

This creates a short-term

exemption from funding expenditure such as depreciation. However, it also

reduces the cash available to balance against debt and therefore results in a

net increase of debt. Legal requirements of prudent financial management

would need to be considered.

· Amending the

acceptable planning target for the debt-to-revenue ratio

A movement from the current

target of 235% to the maximum allowable under debt covenants of 250% would

provide some limited ability to increase debt (whether related to more capital

projects, reduction of funded depreciation, or the need to fund operating

expenditure) for the same amount of projected revenue.

14. Combined

together the above constitutes a significant body of work. That body of

work has twin objectives.

15. Firstly,

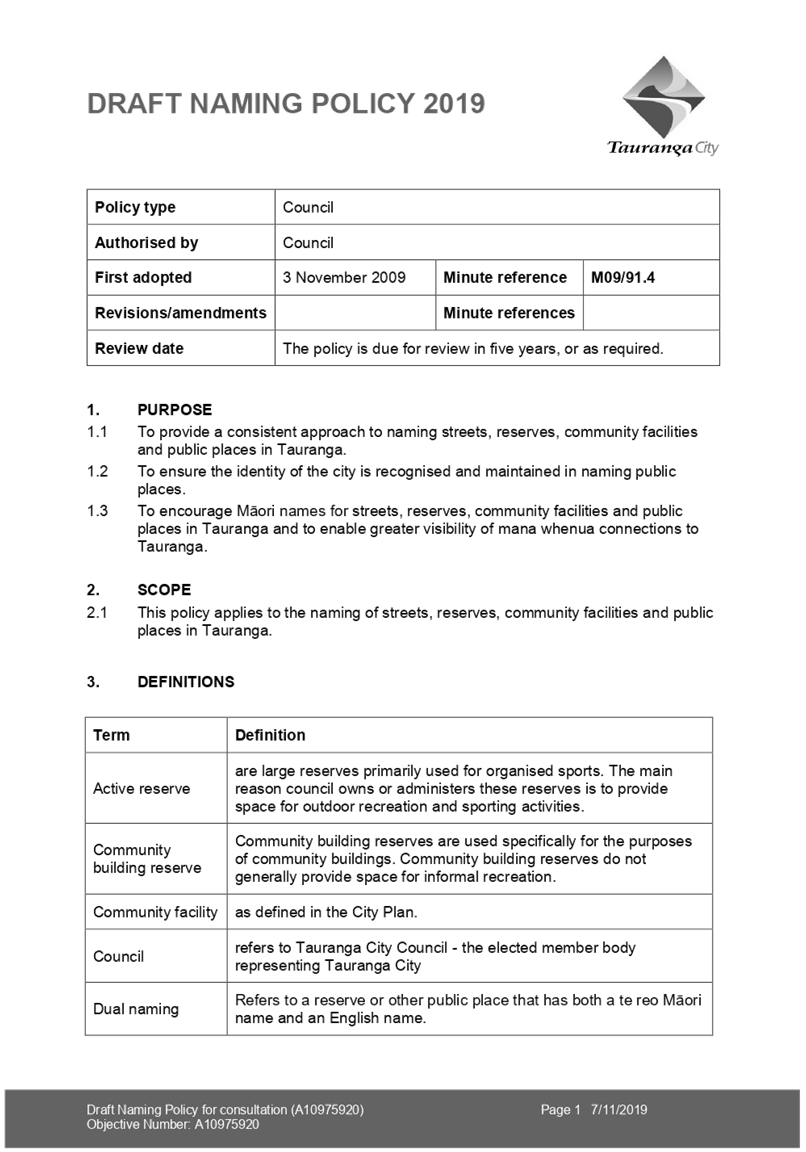

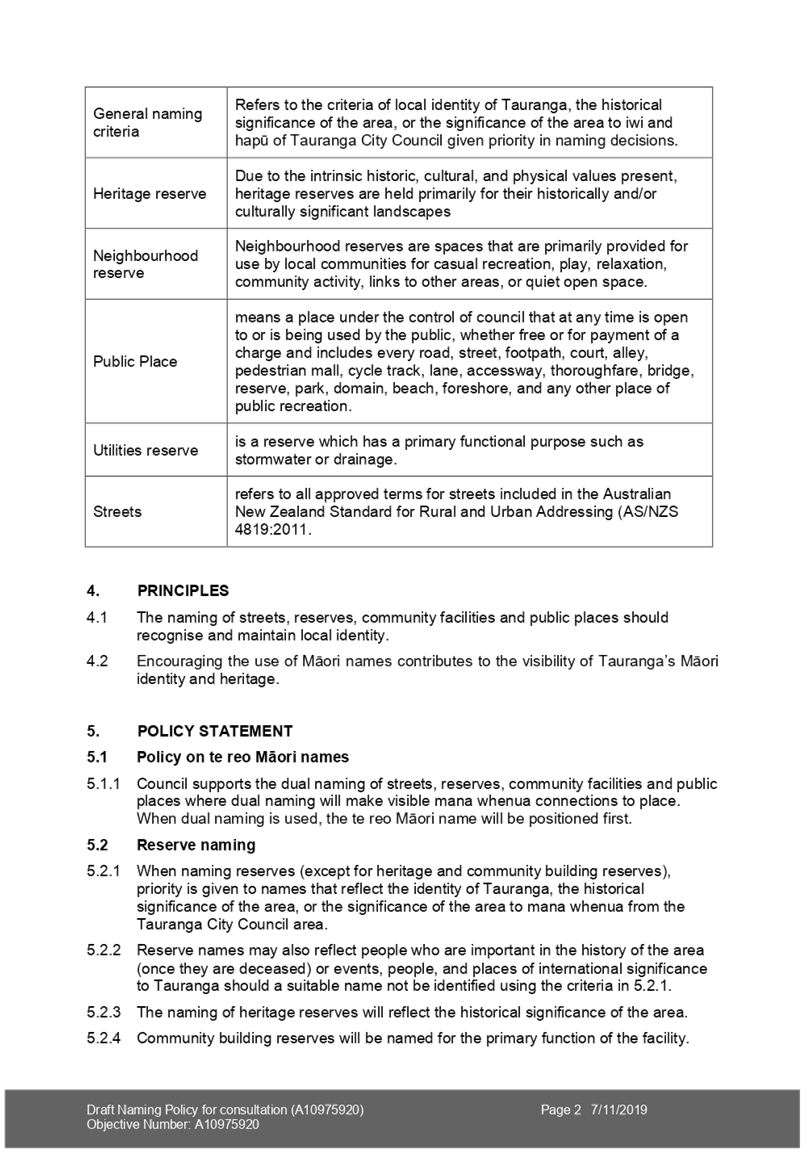

there is the need to develop an Annual Plan for the 2020/21 year which

represents prudent financial management, is sustainable for Council and its

community, is affordable for Council and its community, and is based on the

best available information at the time it is adopted.

16. Secondly,

this body of work will provide a more complete suite of information to base

further engagement with partners on regarding the implications of COVID-19

disruption on Council’s finances and service capacity.

17. The

next sections of this report consider the first three of the

‘levers’ noted above.

lever 1 – Reducing the